Part of the Project

First Published in

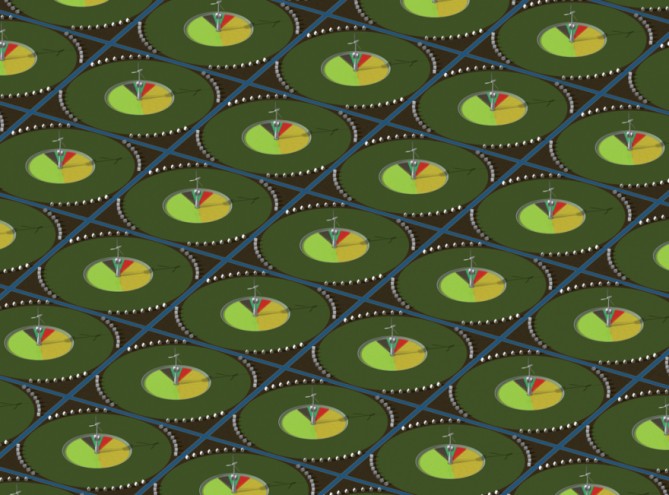

While other kids were drawing trucks and butterflies, Frank Tjepkema was using his crayons to explore how astronauts go to the toilet. Coming full circle, Tjepkema’s newest Oogst project about self-sufficient agricultural systems harks back to his childhood interest of closed-system space shuttles.

With a diverse and thought-provoking portfolio to account for his eight-year-old studio, Tjepkema has worked with the likes of Droog, Ikea, British Airways, the City of Amsterdam, Design Academy Eindhoven, Levis Red and Heineken. An ironic tone underpins much of his work, such as his Shockproof vases, Bling Bling medallion, Signature Vases, XXL Chair and Nest Sofa. Exploring the outmost limits of production capabilities, each work has a distinct manifestation. He has twice won the Dutch Design Award.

Over the past few years, Tjepkema has come to focus more on designing interior spaces than products. Combining conceptual and innovative ideas with functional intelligence and visual elegance, the result is multilayered. Responsible for the unique, ultramodern Heineken concept store in Amsterdam last year, he has also provided turnkey spatial solutions to ROC Professional Training School, Radio 1, Nemo Science Centre, and the Fabbrica and Praq restaurants.

Design Indaba talks to this space explorer about where design is headed.

How did you come to be a designer?

At 17 years old, I had two passions – jazz music and drawing. Intuitively I chose a profession involving drawing because apparently it was slightly more natural for me than music. But I realise today that I have been doing nothing but attempt to implement the qualities of jazz music into my design work. It has become a real mission for me to make intuitive and engaged design. Design that breaks free from modernist dogmas, just as jazz improvisation has delivered us from rigid music structures and melodies.

Reportedly you’ve always actually wanted to be an astronaut, not a designer. How does design manage to live up to such aspirations?

That was even earlier when I was around eight or nine years old, before music came into the picture. I was drawing rockets all the time. I was really interested in the interior arrangement of the rockets and how the astronaut would go to the bathroom. So, yes, I wanted to become an astronaut, but it was more an excuse to draw rockets. Being on the moon is probably pretty boring after the first 15 minutes anyway!

For a while your design interest rested strongly in brands, ultimately culminating in the Bling Bling medallion. What is your attitude towards designing for brands?

I’m really interested in brands from a sociological point of view. Why do we need them? Why do we like them? What need do they fulfil besides the purely practical part of the products they bring to us? I find that really fascinating because it’s a reflection of society, trends and so on. But I think brands should use their influential power very responsibly and that’s usually not the case.

Yes, they claim that they are responsible, but when it comes to communication, usually they are really just trying to push as many products as possible. KesselsKramer in Amsterdam is one of the few branding and advertisement agencies that really manage to combine commercial targets with social engagement. A company that inspires us a lot, we have enjoyed having the chance to work with them on different occasions.

What are your predictions regarding the future of brands in relation to the changing world economy and consumption habits?

I think a brand like Nike will have to change radically if they want to regain the cult status they had in the 1990s. They represent globalism at its peak and we now know that’s not the path towards a sustainable economic or ecological model.

From a design point of view, the open source model and the democratisation of production facilities may well be an important development. By this I mean, for example, the future possibility of printing your products at home.

In turn, brands like Camper are falling more into context thanks to their laidback communication angle – nowadays “Walk, don’t run” sounds much better than “Just do it”. “Just do it” sounds just plain irresponsible these days. Funny how in just 10 years Camper falls into context and Nike falls out of context.

You have also done work for Ikea. What are your thoughts around mass-production vs limited-edition?

Ikea is perfect for furnishing children’s rooms because the average lifespan of an Ikea product is about four years (in my experience). I try to keep Ikea out of my living room because there I need products that I can love and cherish for a longer time. I have done design work for Ikea, but unfortunately it was not realised.

Although your diverse output includes packaging, products, furniture and events, your interest in design for brands seems to have naturally evolved into working a lot on interior designs over the past few years. What is this evolution and its appeal?

Interior design for commercial and public spaces is interesting because it is the ultimate crossing point between experience design, 3D design and branding. Design is just another communication form next to language, music or film – at least I regard it as such. Functionality for me is absolutely important, but from a totally different angle than the communication aspect of design.

Functionality is binary – it works, it doesn’t work, on or off. Communication is layered and complex. It has an intellectual dimension, an emotional dimension, a cultural dimension... This is an exaggerated representation, but it makes my point that function for me is subordinate to communication. The topic of functionalism makes me want to go to sleep. It’s so self-evident.

Images of the Amstel Station really show that, as opposed to products that envision one end-user, public spaces have to consider multiple users and interpretations. What is your particular philosophy when designing public spaces?

Linked to my previous answer, the Amstel Station is a communication project about facilitating interaction between people in a physical context. We are going beyond a typical brief with a couple of requirements, such as how many people should be able to sit, how big, etc. We are offering different ways to sit, different group configurations and different levels of intimacy within one furniture concept.

That makes a lot of sense in a public space because there are all types of users, of different ages and cultures, who will be interacting with the furniture. How on Earth is it logical to file rows of identical seats, which is happening in just about every airport I’ve seen?

All of your work shows a predilection towards unusual and intricate forms. What is your relationship with the production cycle?

Well I am very aware of requirements that arise from mass-production. I have seen some mass-production projects cancelled because we were thinking too complexly. Mass-production requires simplicity by its very nature. Our Waater bottle is an example where simplicity met the production requirements, while we still managed to maintain a strong iconic shape. Jewellery is another story. It’s a small series and here complexity leads to amazement.

You also explore the notion of “open source design” with your Shockproof and Signature Vases, for instance. What are your thoughts on open source design – does it undermine the existence of the designer?

Open source design is part of an anti-globalist impulse directly fed by the necessity for change as a consequence of the global economic and ecological crisis. It’s not merely about aesthetics. Two things with regards to undermining the existence of the designer: Everybody having access to software like Photoshop has not made graphic designers disappear, and having Garage Band on every Mac has not made musicians disappear.

A part of the design and manufacturing process may well move towards the consumer and it’s very interesting to see what that parameter means with regards to new design concepts. Personalisation is, in my opinion, the most obvious advantage of open source. But again, even though everybody has access to music instruments, not everybody can make great music. So I’m not really worried. However, maybe other copyright models will have to be developed to address the concept of open source in design.

In your Oogst concept designs, you explore all-encompassing closed systems. Is this something that will start coming through in your other work?

The funny thing is that my first rocket drawings were pretty much closed systems. So it’s something of a fascination that is coming back, fed by recent developments in society.

While other kids were drawing trucks and butterflies, Frank Tjepkema was using his crayons to explore how astronauts go to the toilet. Coming full circle, Tjepkema’s newest Oogst project about self-sufficient agricultural systems harks back to his childhood interest of closed-system space shuttles.

With a diverse and thought-provoking portfolio to account for his eight-year-old studio, Tjepkema has worked with the likes of Droog, Ikea, British Airways, the City of Amsterdam, Design Academy Eindhoven, Levis Red and Heineken. An ironic tone underpins much of his work, such as his Shockproof vases, Bling Bling medallion, Signature Vases, XXL Chair and Nest Sofa. Exploring the outmost limits of production capabilities, each work has a distinct manifestation. He has twice won the Dutch Design Award.

Over the past few years, Tjepkema has come to focus more on designing interior spaces than products. Combining conceptual and innovative ideas with functional intelligence and visual elegance, the result is multilayered. Responsible for the unique, ultramodern Heineken concept store in Amsterdam last year, he has also provided turnkey spatial solutions to ROC Professional Training School, Radio 1, Nemo Science Centre, and the Fabbrica and Praq restaurants.

Design Indaba talks to this space explorer about where design is headed.

How did you come to be a designer?

At 17 years old, I had two passions – jazz music and drawing. Intuitively I chose a profession involving drawing because apparently it was slightly more natural for me than music. But I realise today that I have been doing nothing but attempt to implement the qualities of jazz music into my design work. It has become a real mission for me to make intuitive and engaged design. Design that breaks free from modernist dogmas, just as jazz improvisation has delivered us from rigid music structures and melodies.

Reportedly you’ve always actually wanted to be an astronaut, not a designer. How does design manage to live up to such aspirations?

That was even earlier when I was around eight or nine years old, before music came into the picture. I was drawing rockets all the time. I was really interested in the interior arrangement of the rockets and how the astronaut would go to the bathroom. So, yes, I wanted to become an astronaut, but it was more an excuse to draw rockets. Being on the moon is probably pretty boring after the first 15 minutes anyway!

For a while your design interest rested strongly in brands, ultimately culminating in the Bling Bling medallion. What is your attitude towards designing for brands?

I’m really interested in brands from a sociological point of view. Why do we need them? Why do we like them? What need do they fulfil besides the purely practical part of the products they bring to us? I find that really fascinating because it’s a reflection of society, trends and so on. But I think brands should use their influential power very responsibly and that’s usually not the case.

Yes, they claim that they are responsible, but when it comes to communication, usually they are really just trying to push as many products as possible. KesselsKramer in Amsterdam is one of the few branding and advertisement agencies that really manage to combine commercial targets with social engagement. A company that inspires us a lot, we have enjoyed having the chance to work with them on different occasions.

What are your predictions regarding the future of brands in relation to the changing world economy and consumption habits?

I think a brand like Nike will have to change radically if they want to regain the cult status they had in the 1990s. They represent globalism at its peak and we now know that’s not the path towards a sustainable economic or ecological model.

From a design point of view, the open source model and the democratisation of production facilities may well be an important development. By this I mean, for example, the future possibility of printing your products at home.

In turn, brands like Camper are falling more into context thanks to their laidback communication angle – nowadays “Walk, don’t run” sounds much better than “Just do it”. “Just do it” sounds just plain irresponsible these days. Funny how in just 10 years Camper falls into context and Nike falls out of context.

You have also done work for Ikea. What are your thoughts around mass-production vs limited-edition?

Ikea is perfect for furnishing children’s rooms because the average lifespan of an Ikea product is about four years (in my experience). I try to keep Ikea out of my living room because there I need products that I can love and cherish for a longer time. I have done design work for Ikea, but unfortunately it was not realised.

Although your diverse output includes packaging, products, furniture and events, your interest in design for brands seems to have naturally evolved into working a lot on interior designs over the past few years. What is this evolution and its appeal?

Interior design for commercial and public spaces is interesting because it is the ultimate crossing point between experience design, 3D design and branding. Design is just another communication form next to language, music or film – at least I regard it as such. Functionality for me is absolutely important, but from a totally different angle than the communication aspect of design.

Functionality is binary – it works, it doesn’t work, on or off. Communication is layered and complex. It has an intellectual dimension, an emotional dimension, a cultural dimension... This is an exaggerated representation, but it makes my point that function for me is subordinate to communication. The topic of functionalism makes me want to go to sleep. It’s so self-evident.

Images of the Amstel Station really show that, as opposed to products that envision one end-user, public spaces have to consider multiple users and interpretations. What is your particular philosophy when designing public spaces?

Linked to my previous answer, the Amstel Station is a communication project about facilitating interaction between people in a physical context. We are going beyond a typical brief with a couple of requirements, such as how many people should be able to sit, how big, etc. We are offering different ways to sit, different group configurations and different levels of intimacy within one furniture concept.

That makes a lot of sense in a public space because there are all types of users, of different ages and cultures, who will be interacting with the furniture. How on Earth is it logical to file rows of identical seats, which is happening in just about every airport I’ve seen?

All of your work shows a predilection towards unusual and intricate forms. What is your relationship with the production cycle?

Well I am very aware of requirements that arise from mass-production. I have seen some mass-production projects cancelled because we were thinking too complexly. Mass-production requires simplicity by its very nature. Our Waater bottle is an example where simplicity met the production requirements, while we still managed to maintain a strong iconic shape. Jewellery is another story. It’s a small series and here complexity leads to amazement.

You also explore the notion of “open source design” with your Shockproof and Signature Vases, for instance. What are your thoughts on open source design – does it undermine the existence of the designer?

Open source design is part of an anti-globalist impulse directly fed by the necessity for change as a consequence of the global economic and ecological crisis. It’s not merely about aesthetics. Two things with regards to undermining the existence of the designer: Everybody having access to software like Photoshop has not made graphic designers disappear, and having Garage Band on every Mac has not made musicians disappear.

A part of the design and manufacturing process may well move towards the consumer and it’s very interesting to see what that parameter means with regards to new design concepts. Personalisation is, in my opinion, the most obvious advantage of open source. But again, even though everybody has access to music instruments, not everybody can make great music. So I’m not really worried. However, maybe other copyright models will have to be developed to address the concept of open source in design.

In your Oogst concept designs, you explore all-encompassing closed systems. Is this something that will start coming through in your other work?

The funny thing is that my first rocket drawings were pretty much closed systems. So it’s something of a fascination that is coming back, fed by recent developments in society.