First Published in

The kingdom of Mapungubwe in Limpopo Province is at the heart of Beverley Price’s hybrid gold artwork, Mapungubwe Re-Mined, which is on display at the Gold Museum of Africa in Cape Town from the last week of November 2006.

A jewellery artist, Beverley found her engagement with Mapungubwe allowed her to set aside her ambivalence about working with gold and to recontextualise it as a jewellery medium in South Africa.

According to Beverley, goldsmiths at Mapungubwe produced some of the finest gold artwork found on the African continent, which they traded with the East. A hoard of burial gold was found there in 1930s – including a small gold rhinoceros, which stands as a symbol for this Iron Age metropolis and the African renaissance today.

It was not until the post-apartheid years that the gold objects of Mapungubwe saw the light of day, however, and Beverley feels that colonialist discourse had much to do with this.

“I had put gold on the back-burner since 1995, not really expecting to find a right attitude to work with it,” she says. “Mapungubwe... provided me with a new reference point and rationale for using gold, a way to circumvent the colonial history of the precious mineral industry.”

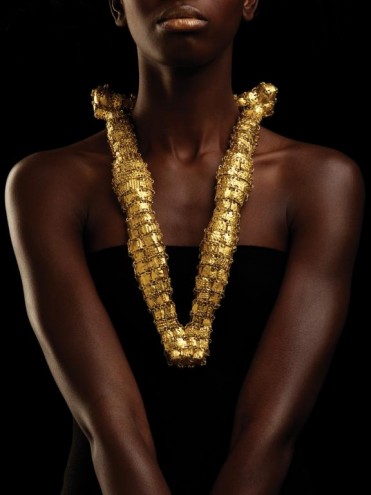

Mapungubwe Re-Mined is made of fine gold and 18-carat gold wire and gives the symbolic rhinoceros prominence by having stamped images of it appear at the most prominent points of the work – the knobs and central back section.

Since 2000, Beverley’s interest has been to suggest and promote the use of the Mapungubwe artefacts, including the rhinoceros, sceptre, crown/bowl and beads as hallmarks for the various carats of gold jewellery exported or made in South Africa.

She has created four hallmark platelets, which are on the back of the piece, with the Mapungubwe rhinoceros image, Beverley’s name, the carats of gold used, and the year – all in accordance with the international hallmarking conventions.

The textures on the fine gold foil include chevrons and dots/pocks in relief, which reference the scarified torsos of the BaLemba women from the original Mapungubwe excavation area and appropriate their original visual lexicon.

The neck-piece is a hollow and articulated tubular form with no clasp. Beverley found she could create a large presence with its volume without necessitating a commensurate mass increase although it weighs 524g. The wearer contributes to the form as it ‘achieves’ full form when worn. It is percussive and reminiscent of a skull or a goat’s head. It is not gender-specific and in Africa a man or a woman could wear it.

“My design intention in returning to gold is to equate the power of gold with the boldness of the design and to align myself with the ancient, venerated and powerful visual statements through Adornment in Africa,” explains Beverley. “My connecting with the pre-colonial goldsmithing and our indigenous heritage practices will, I hope, encourage other jewellers in South Africa towards making work with a new hybrid aesthetic as the other applied arts (clothing, graphics, architecture) in South Africa have already achieved.” This will create fresh design, she believes. The work is featured on the World Gold Council website from November and is available to order by commission as well as a range of jewellery in this style.

The kingdom of Mapungubwe in Limpopo Province is at the heart of Beverley Price’s hybrid gold artwork, Mapungubwe Re-Mined, which is on display at the Gold Museum of Africa in Cape Town from the last week of November 2006.

A jewellery artist, Beverley found her engagement with Mapungubwe allowed her to set aside her ambivalence about working with gold and to recontextualise it as a jewellery medium in South Africa.

According to Beverley, goldsmiths at Mapungubwe produced some of the finest gold artwork found on the African continent, which they traded with the East. A hoard of burial gold was found there in 1930s – including a small gold rhinoceros, which stands as a symbol for this Iron Age metropolis and the African renaissance today.

It was not until the post-apartheid years that the gold objects of Mapungubwe saw the light of day, however, and Beverley feels that colonialist discourse had much to do with this.

“I had put gold on the back-burner since 1995, not really expecting to find a right attitude to work with it,” she says. “Mapungubwe... provided me with a new reference point and rationale for using gold, a way to circumvent the colonial history of the precious mineral industry.”

Mapungubwe Re-Mined is made of fine gold and 18-carat gold wire and gives the symbolic rhinoceros prominence by having stamped images of it appear at the most prominent points of the work – the knobs and central back section.

Since 2000, Beverley’s interest has been to suggest and promote the use of the Mapungubwe artefacts, including the rhinoceros, sceptre, crown/bowl and beads as hallmarks for the various carats of gold jewellery exported or made in South Africa.

She has created four hallmark platelets, which are on the back of the piece, with the Mapungubwe rhinoceros image, Beverley’s name, the carats of gold used, and the year – all in accordance with the international hallmarking conventions.

The textures on the fine gold foil include chevrons and dots/pocks in relief, which reference the scarified torsos of the BaLemba women from the original Mapungubwe excavation area and appropriate their original visual lexicon.

The neck-piece is a hollow and articulated tubular form with no clasp. Beverley found she could create a large presence with its volume without necessitating a commensurate mass increase although it weighs 524g. The wearer contributes to the form as it ‘achieves’ full form when worn. It is percussive and reminiscent of a skull or a goat’s head. It is not gender-specific and in Africa a man or a woman could wear it.

“My design intention in returning to gold is to equate the power of gold with the boldness of the design and to align myself with the ancient, venerated and powerful visual statements through Adornment in Africa,” explains Beverley. “My connecting with the pre-colonial goldsmithing and our indigenous heritage practices will, I hope, encourage other jewellers in South Africa towards making work with a new hybrid aesthetic as the other applied arts (clothing, graphics, architecture) in South Africa have already achieved.” This will create fresh design, she believes. The work is featured on the World Gold Council website from November and is available to order by commission as well as a range of jewellery in this style.