Part of the Project

First Published in

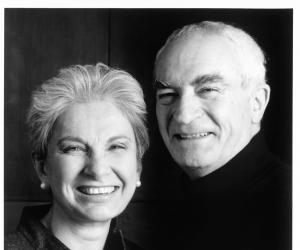

Massimo Vignelli lives by his own design. Pants, suits, accessories, furniture, tableware, pictures… even the apartment itself, are all designed by himself and wife, Lella; not to mention the office and its complete kit. Even when he travels on the New York subway, he is surrounded by the signage that he designed. “If you can design one thing, you can design everything,” is his famous catchphrase.

He explains in his thick Italian-American brogue: “Our approach to design has always been as an organisation of information instead of an art. We don’t think design is an art to begin with – it’s design and noble enough not to borrow qualification from another field. The more design goes to art, the less design it is; and art the same – the more it goes to design, the less artistically interesting it is.”

The challenge of establishing design as a noble, self-validating discipline is something that has underpinned Vignelli’s 55-year career. As such, his impeccable, voluminous design portfolio spanning the whole field of design – graphic, packaging, book, magazine, newspaper, interior, furniture, product – is secondary to the immense influence he has wielded in shaping design as a profession. This Italian “don of design” has spread organised design much further than his Italian brethren have done for organised crime.

Born in Milan, Vignelli studied architecture in Milan and Venice, and worked with the renowned Castiglioni Brothers before relocating to New York in 1965 to co-found the influential Unimark International Corporation. The largest multinational design and marketing company the world had then seen, Unimark’s short 12-year existence belies its importance. Paramount in shaping international design aesthetics, formative in its approach to corporate design and groundbreaking in establishing a commercial structure for design companies, its far-reaching effect is “the design industry” of today.

“We had the intention of bringing a certain kind of design to large corporations. At the time, large corporations were using a trivial kind of communication. Only small companies here and there saw the value of good graphic design. We wanted to affect the environment, so we set up a large corporation to be at level with the large clients, because we had experienced before that as a small individual, you couldn’t reach the large clients,” Vignelli explicates.

Ambitiously, Unimark started out with four offices – New York, Milan, Chicago and San Francisco. Once they started getting large clients like Ford, offices multiplied to include Detroit, Denver, Cleveland, London, Copenhagen, Melbourne, Johannesburg and others. “The diffusion of a certain approach seemed the best way to eliminate or substitute the giant, but of course we just became more sophisticated bullies than them,” chuckles Vignelli.

“The idea was to spread the language of design, which was rather new at the time,” Vignelli shrugs as though instigating a design insurrection was an everyday matter. Of course, little did he then know that this language would remain the lingua franca of good design today. For instance, page through the Vignelli Canon that he e-published for Christmas last year and it becomes clear that there is hardly a designer in the world who wittingly or unwittingly works without Vignelli looking over their shoulder.

“The fight is still the same,” Vignelli nods. “Intellectual elegance fighting against intellectual vulgarity. We keep fighting for a better quality design, because we know that when you are surrounded by a better quality of design it effects your behaviour, way of thinking and might even make you a better person and thus a better world.”

For Vignelli, universal change does start with a font. Although not responsible for designing it, Vignelli is pivotal in the global domination of Helvetica. Designed in 1957 and available from 1960 on limited distribution in Europe, it only crossed the Atlantic in 1965 with Vignelli. Immediately it became distributed throughout the US in Unimark’s multiple offices and, because of Unimark’s influence and growth, also rapidly spread across the world.

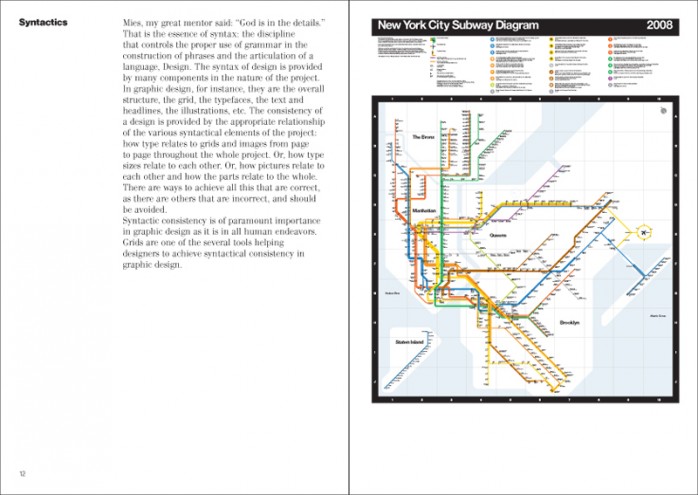

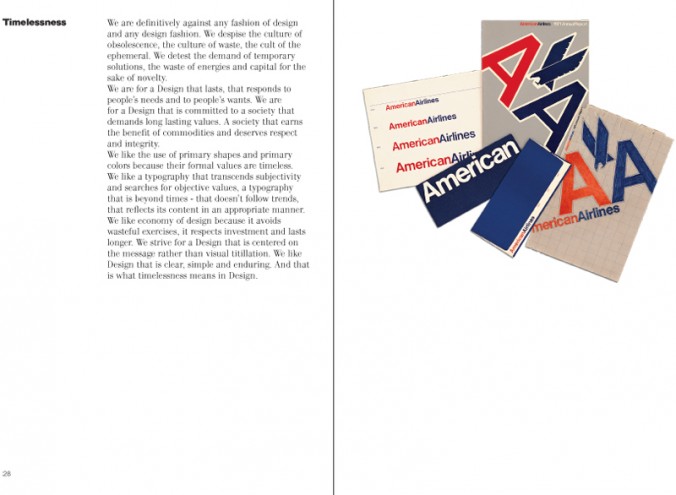

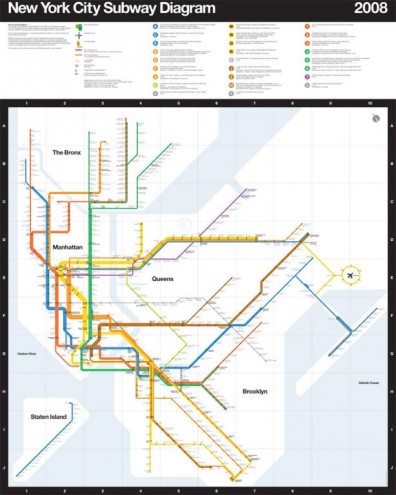

“With its particular typographic structure and iterance of size and space, it became very popular and the perfect word for a certain language,” he explains in the same matter-of-fact tone in which he dismisses Unimark’s decline as “necessary”. Following Unimark, Massimo and Lella established Vignelli Associates in 1971 and Vignelli Designs in 1978, and here created most of their widely recognised work; including the corporate identity of American Airlines, the iconic signage for the New York Subway System and his critically appraised 1978 Subway Map – which was given a limited-edition reprint in 2008.

These days it is hard to imagine any multinational company, let alone a design company, functioning before computers and the internet. But Vignelli points out that the principles of design – grids, simplified type etc – existed long before the computer, now it’s just faster. “It’s amazing that even with a computer, one complains that it’s too slow. Too slow compared to what? Compared to the time when we were cutting the type letter by letter?”

But, Vignelli admonishes, “The way of working in design has changed tremendously in the past 20 years through the advent of the computer. The computer has made the possibility of achieving fabulous typography much greater than in the past 500 years, but at the same time it has also increased the possibility of making the worst things ever. It’s a funny instrument – we’re in a time where you can do the best or worst thing. So it is important to remember that the best is not a random result.”

Approaching 80 years of age, Vignelli knows no concept of retirement and insists that he will work forever. In fact, he’s quite excited about the new challenges of the 21st century. Judging by the way his eyes light up, there seems to be one more thing he wants to definitively stamp into the design discipline: “‘Less is more’ is the greatest thing we have for the near future, to overcome a lot of situations due to the economic crisis – less money is more, less consuming is more. We’ll still need things but our choices will not be as stupid as before.”

Enthusiastically, Vignelli continues: “There is a tremendous change that is going to happen and it is going to change the mentality, culture and taste of people, and thereby it’s going to change design. Design will not be what we’ve had in the past 50 years. It’s going to become sober. Modern design was born in the depression, which is a good thing about depressions – they wake people up. Nothing can make people more drowsy than comfort and money. Greed is dead. It’s like a gas that makes people sleep easy, letting some people grab everything. In that kind of culture, nothing can provoke anything new. So this economic situation that we’re in now is going to provoke a fantastic culture of cleaning.”

He is, however, worried that without a formalised history, theory and criticism, design may short-change itself in the future, as a circular discipline constantly chasing the newest-new. “Creativity is a by-product of intelligence and rules are the products of knowledge. So you could be very creative but not have knowledge of the rules and not be able to make choices regarding which rules can be useful. They are both needed, but the origin of one is intuition and the other experience.”

Download the Vignelli Canon here: www.vignelli.com/canon.pdf