Part of the Project

First Published in

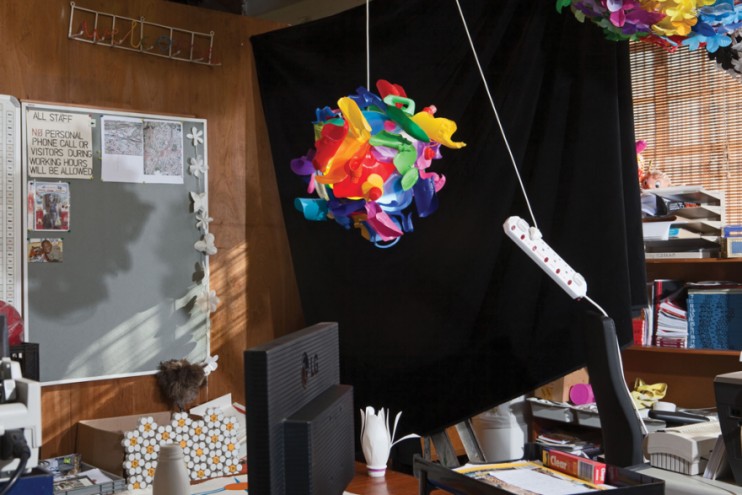

Heath Nash: The past six years for me have been an exploration of re-use. I am also really interested in different types of craft, and bringing craft into a more contemporary and relevant state for contemporary consumers. Also, by using a process of exploration in my work, I tend to try things out and see what happens, rather than knowing what I want to do before I start. And you?

Hella Jongerius: It is so difficult to do the elevator pitch about your past ten years. I’m only interested in crafts in an industrial context. I have been working in this space for the past ten years, and have been developing a language of individual science that comes out of crafts and archives. Heath, why do you only do lighting?

Heath: It is just what I have started with. I have lots of other interests and want to do other products, but it hasn’t really happened yet. This year I have been focusing a lot on mastering the business aspects of my studio, because previously I had absolutely no business knowledge. I have been getting tools together so that I can manage the business properly and also start to extricate myself from the running of the business, so that I can focus on other projects that I can really throw my creativity at.

Hella: I know that lights are easier to make your money with, because it is a simpler product to make and it is also a product that all consumers need a few of.

Heath: I am also interested in working with traditional craft techniques. I am currently in Coffee Bay in the Eastern Cape, where I’m going to be working with some weavers. I am keen to start exploring larger objects and furniture with these new artisanal techniques that I am learning to work with.

Hella: Like the project in Zimbabwe?

Heath: Yes, that was last year. It was an amazing, exciting process. It made me see that the people that I was working with are almost like human machines, because they are so good at what they do.

Hella: I also did something with local crafts. I did a project with students in Brazil and a project for Ikea with women in India.

Heath: Yes, those beautiful wall hangings with animals!

Hella: Yes. Working with craft people, the products always look beautiful because it mostly comes from traditions and people are very skilled. It is a pleasure to work in that way, but the difficulty is the logistics and the marketing afterwards. It is very difficult because you have small quantities, and the distribution is quite hard and expensive. You need a powerful company to get the products to fly.

Heath: Exactly, that is what I have also found and I don’t know how it is going to be overcome because it is the biggest problem. I am interested in the business side of your studio. How did you learn those skills? Are you involved in the logistics? It is very complicated stuff and you have so many products in the making all the time.

Hella: Well, I think I was born with some.

Heath: You are lucky!

Hella: My father is an entrepreneur, so I have got it in my blood. It’s easy for me to run a studio. The companies I work with take care of the production, marketing and selling of the products that we develop together, so the whole business part. I receive royalties if I do a good job.

Heath: In South Africa there aren’t companies like that.

Hella: But don’t you have an agreement with Artecnica?

Heath: Oh yes, I do.

Hella: Artecnica is a businessman or agent who takes care of the product. So you hire your craft people or they have craft people all over the world, and they sell it for you. Not only do they sell it for you, but they do the packaging and the very important part of making a product a success. The company is a very nice company to work for.

Heath: What did you do with Artecnica?

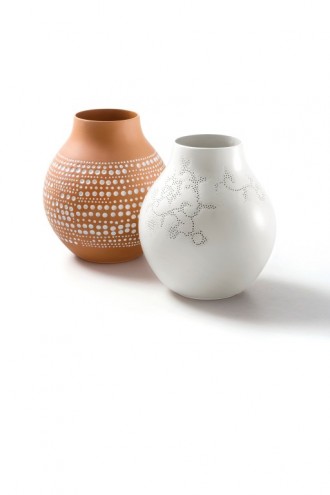

Hella: I made bowls and black plates with beads on it. I did not work with the craft people myself because it was in a dangerous drug district. We did it all by post, Fedex, email and whatever, and there was quite a lot of to-and-fro but in the end it all worked out. It was a nice experience.

Heath: I long for the restrictions that come with working for a client and having them produce for you. If you work with a Vitra or Ikea, they give you certain parameters that you have to work within and I think that is quite exciting, because you know where the boundaries are. If everything is self-produced, there is too much option out there and so it becomes more difficult in a way.

Hella: That is true. Within boundaries you need your creativity because you know where you are headed and how small your pocket is.

Heath: Price is very important. Artecnica produced one of my lamps called the Anemone, but it was so difficult to make that it ended up being too expensive. It is in production, but it doesn’t sell very much. I do have a few other simpler ideas that I would like to do with them, but they haven’t come to fruition yet. I love how you think about sales being the ends, that the product proves to be successful once it sells enough.

Hella: I think it is part of your duty in the end to develop products that are a success on all levels and that there is somebody that is willing to pay that amount for the product. You are not an artist, you are a designer, so you work for a consumer market.

Heath: What are you working on at the moment, Hella?

Hella: I just finished an exhibition that I did in Holland to show the past 15 years of my work and there is a book called Misfit, published by Phaidon. That has really kept me busy for the past half a year. I moved to Berlin two years ago and changed from working with a studio, to working alone again. I still design new products for companies, but I use freelancers that I have worked with for a long time to help me. By being alone, I wanted to concentrate more on abstract subjects, not just doing chairs and things, but more research and experiments. Now I can just wander around in subjects. I have been doing a lot of work and research around “colour”.

Heath: That sounds very, very nice.

Hella: That I am able to do this, is a luxury of the success that I have. I could have grown and had a big studio with a lot of people, but I wanted to use the money that I gained to take the time to explore the depths of my profession.

Heath: What is your opinion on the differences between art and design? What you are describing seems to be my idea of an artist’s existence.

Hella: I think that an artist makes different projects to a designer, which have nothing to do with whether you are alone or in a team. A designer works for a market, so a product has to function in a normal environment, also price wise. Dealing with industry is a big part of being a designer. So, there is a difference for me although it is also fluid.

Heath: I can’t help wondering what your reflection and research is going to lead to. Would you be open to making art?

Hella: No. The work I have been doing is about industrial production. What has been lost in products since the industrial revolution – there’s a lot wrong. I design individual products produced in series, showing the hand of the maker, with interesting details and celebrating imperfection. This is a rethink of quality! That’s the reason why I now work in colours. I miss a colour world that is no longer there – the industrial recipes are very poor because of standardisation. I’m researching colour from a design perspective.

Heath: Was it colour specifically in relation to one material or is it across the board that you are researching?

Hella: It is not one material, it is really researching industrial recipes for colours, in which the pigments are poor and mixed economically. In research, you look at alternatives. Considering the kind of work that I see in paintwork in art, why has this been lost to the industrial world? The industrial tests are killing the quality. There’s a test that says that a colour has to be the same in the morning as in the evening. I think that changing with the light is the beauty of a colour – that’s quality! We as designers have to work with this poor industrial sterilisation of the system.

Heath: In a way you are designing colour?

Hella: Yes. Not in terms of trend watching, but in terms of wanting to have a richer colour. For the exhibition, I made 15 very nice colourful blacks. A world that you cannot buy in industrial pigments.

Heath: That could help many other designers with the work that they make as well.

Hella: Yes, that is the idea.

Heath: I am very envious of the Dutch way of thinking and of Dutch design schools. I am amazed at all the work that comes out of Eindhoven and am very respectful of how the people of your country think about design. As designers, we are thinkers. Why I like working with artisans in South Africa is that while they have production systems and they make very nice things, they don’t think beyond making the same thing. What I was doing in Zimbabwe and what I would like to do here in Coffee Bay is to start working with these artisans and to start introducing them to ways of thinking about innovation instead of just production. I think that if that can be taught and shared with these communities that are struggling, then at least it gives them a way to work forward both in their design and in their lives.

Hella: I think that innovation is very important and I think that innovation is a very important word if you are a designer. If you don’t innovate in your profession or if you don’t innovate in making a new chair or in a new method, I think that it is no longer interesting. Innovation is not only important in our profession. Besides the best Dutch design, I think that there is also a lot of rubbish, but the good designer questions the profession. This is something that you could do: Questioning the profession and trying to come up with an alternative world.

Heath: This whole thing of re-use that I am interested in is questioning the world and how things look already. Why does the packaging design look the way it looks? Why does a bottle look like a bottle? I think there is no need for a bottle to be bottle-shaped. I’d like to ask plastics producers whether there can’t be more to a bottle than simply carrying your bleach home? Whether one can build a second function into the structure of what we take for granted now. However, I struggle to speak to industry and get them to understand what I can offer. Something that really interested me about your earlier work is that it was self-initiated and then taken up by industry. I don’t know if you have an easy answer for this, but how did you make that crossover?

Hella: I always say that this takes eight years of showing what you can do. Everyone can see what you are doing and if they call you, they know what they get. I think that is very important. They need to know what your handwriting and opinions are, companies want to be safe. Then on a certain day a phone call will come and people will want something from you. I think that it is just a matter of patience and determination with what you are doing, because you know you are doing a good job.

Heath: Then I’ve still got a while to go as I only started in 2004!