Part of the Project

If the sport of surfing is a marginal activity – a lifestyle pursued outside the mainstream and traditionally associated with hippies, dropouts and stoners – then surfboard design is similarly maligned, never really having enjoyed the spotlight as a serious form of design. Which is just fine by Laurie and Gary Holmes who reject the sport of surfing anyway. They reject the multi-billion dollar surf industry. They reject the ASP (Association of Surfing Professionals) World Tour. They reject the radical aerial manoeuvres of the new generation of young pros. They even reject the Thruster; the three finned ’80s design that is so universally acknowledged as the pinnacle of surfboard design that it hasn’t been challenged in over 30 years (and is still the surfboard of choice for 99.9% of surfers worldwide).

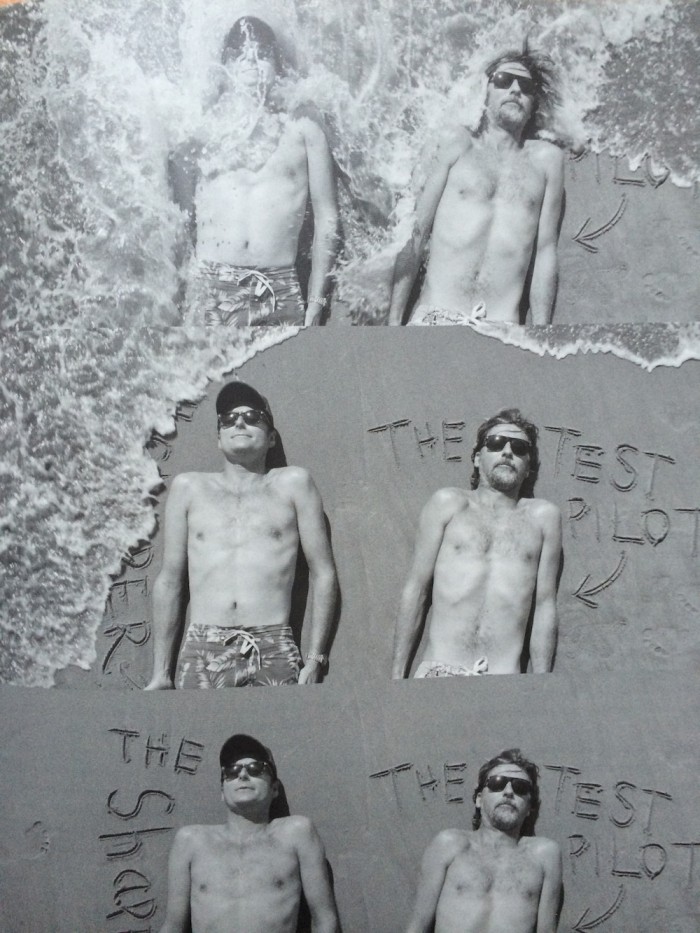

Yet Laurie and Gary are two of the most ‘stoked’ surfers you’re likely to find.

So why do they reject the sport of surfing? Well, firstly they’re likely to tell you that surfing is an art form, not a sport. Secondly it’s because they feel that surfing has lost its marginal status. It’s been corporatized, homogenised and sanitised to the point where it is no longer outside the mainstream. And those hippies, dropouts and stoners were exactly the guys who turned Laurie and Gary on to surfing in the first place. That notion of doing something different, something radical, was and still is central to the Holmes brothers’ love of surfing.

The radical tendencies started way back in the early ’80s when, like the other kids his age, Laurie would order his surfboards from Durban’s local shapers. But unlike the other kids, Laurie was never quite satisfied with the boards he wound up with. So when his aunt in Florida began sending him surfing magazines and he saw what was happening in surfboard design in the States – usually months before those same magazines appeared on the shelf at CNA – he decided he’d start designing and making his own boards.

Before long Laurie was turning up at the district surf contests carrying surfboards like no-one had seen before in Durban. He was quickly noticed by the local manufacturers – and not in a good way. He was soon banned from surf shops and shaping bays all over Durban, the shapers even refusing to sell him the materials needed to make his boards. Fortunately he was friendly with Azon, a Zulu worker at Graham Hines’ factory, who supplied him with reject blanks (the polyurethane foam core of a surfboard), cheap resin and fibreglass; all he needed to do his thing.

Laurie’s first breakthrough came in 1993, when he came into possession of an old board that had been snapped several times. It just so happened that this board had belonged to surfing legend, Tom Curren and was shaped by Al Merrick who was then and still is, a world leader in modern surfboard design (although true to surfing’s traditions, he is still referred to merely as a shaper). Laurie sliced the board into six-inch cross-sections, fanatically studying the curve of the rails (edges) as they traversed from nose to tail. The slices of the old Al Merrick became Laurie’s blueprint and gave him the insight to elevate his craft to the next level. From that point on, the brothers only surfed boards made by Laurie.

His next leap forward came some years later, when Laurie was invited by Baron Stander to spend some time in his shaping bay. He learned more about crafting surfboards in two days of observing a seasoned shaper than he had in all the years up until then.

But his pivotal moment came in 2008. Hanging out with Wetland – who by then was something of a mentor to Laurie – the conversation turned to a series of strange longboards stacked in the corner. Wetland had been experimenting with the scooped-out hourglass silhouette of snowboards and adapting the contours and design thinking to his longboards. (According to Laurie this was some two to three years before Swedish industrial designer Thomas Meyerhoffer started doing the same thing and getting the attention of the New York Times for his efforts.) Laurie asked why Wetland hadn’t made any shortboards using his design, to which Wetland replied, “Why haven’t you?”

The gauntlet laid down, Laurie hit the shaping bay, emerging a few weeks later with his first truly radical surfboard design. The Stealth was a sexy hybrid of a fish (a thick, squat shortboard with an exaggerated swallowtail) and the hourglass shape that Wetland had been toying with. The fins had been incorporated into the rail, with a pair of small trailer fins tucked between and behind them. The board was incredibly fast and gorgeous to look at, but Laurie and his trusty test-pilot, Gary weren’t sold.

They returned to the shaping bay and emerged with The Stealth v.2. With the same fin configuration but a slightly softened silhouette and the angular swallowtail of its predecessor tempered and rounded, this model provided more control while still offering the glide and speed of The Stealth.

The Clean Line was the next significant step forward, the hourglass silhouette more pronounced and pushed further up towards the board’s nose, while the manta-ray-like fins were abandoned in favour of a more conventional four-fin setup.

The evolution continued with Laurie tweaking and refining and Gary – a standout surfer in any crowd – reporting back. Today, some four years later they have arrived at ‘The Dagger’, the model that is Gary’s current go-to board, although true to form, Laurie has taken an unexpected turn and begun exploring a new shape. Resembling nothing so much as a bar of soap, the P40 Warhawk is based on the Bob Simmons’ planing hull, a ’50s design, which in turn was based on the research of WWII maritime engineer Lord Lindsey. According to Laurie the P40 Warhawk is so named because it “flies”.

When I interview the brothers they talk animatedly about their philosophy and what it is they’re trying to do. But as much as I admire their determination to carve their own path (or as Gary would say, “…ride a different line on the wave”, an unwitting metaphor for their approach to life if ever there was one), I’m here to find out whether what they’re doing has any merit as design innovation. So I ask whether they’d mind me riding one or two of the boards – you know, conduct some field research. A minute later my van is stuffed with half a dozen futuristic foam and fibreglass lozenges and I’m feeling rather excited.

It’s Friday, December 23 – the last day of work before the Christmas/New Year break and in spite of the sense of anticipation – a stack of mysterious boards in my car and the end of the working year at hand – there’s a sickly north easterly blowing and little chance of waves over the next day or two. I put my head down, determined to get as much work done as possible so I can close shop with a clear conscience. But at about 4pm the wind switches and immediately Laurie is on the phone. “Bru, the west is through and there’s a bit of east swell, I reckon we should hit Addington, there could be a couple fun ones.” Five minutes later, my good intentions long forgotten, I’m driving towards the beach. My iPod is on shuffle, and it must sense my good mood because somehow every track sounds like summer and I arrive at the beach ready for action.

Laurie’s there already and he looks sceptical, “Eish bru, this west is pumping hey. Maybe too hard.” The clouds have moved in and the wind is ripping plumes of spray off the back of each wave. The swell looks surprisingly solid too. A couple of surfers are already out but they don’t seem to be getting much.

Laurie and I are um-ing and ah-ing when Gary pulls up.

“Fuuuuck, it’s firing!” he shout’s, already scrabbling about in his van for his boardshorts, “what are you ous waiting for?” His enthusiasm is infectious and soon we’re all pulling on boardies and wetsuit vests. A little put-off by the conditions, I decide to opt for my own board and save the test ride for a more favourable day. “What are you doing?” barks Gary, and I sheepishly slide my board back in and contemplate the easiest option from among my choices. I opt for The Clean Line, lock the car and head down the beach, fighting the wind and trying to find some resonance with this thick, unfamiliar craft under my arm.

For the record, I’m firmly entrenched in the camp of surfers the Holmes brothers despise; I have ridden a thruster my whole life and rarely deviate by more than a half inch here or there on my board’s specs when ordering a new one. I’m what you might call a meat-and-potatoes type surfer. Which works quite well for me thank you very much.

So paddling through the shorebreak and out to the backline on this thing feels very foreign. A set (a series of bigger waves) approaches and I sneak under the pitching lip (crest) of the first one, my left hand slipping off the soft, round rail as I do so. Freed from my grasp, the board lurches upwards and smashes into my face. Not an auspicious start.

I catch my first wave. It shuts down quickly and without an open face to ride, I get little sense of the board. The next one does the same. Meanwhile Gary is surfing circles round me, putting The Dagger through its paces, hooting and generally looking annoyingly polished. The wind begins to ease and I luck into a good righthander. I drop in and push the board through a deep, late bottom turn – a different line, just like the brothers say. I glide up to the top and redirect back onto the wave’s face. Yes, this is fun! Gary’s paddling out and clocks my ride, hooting and yelling and grinning so hard I suspect he enjoyed my ride more than I did.

Over the coming weeks I spend many hours surfing with the Holmes brothers on these weird boards of theirs. I begin to get a feel for them; the boards and the brothers. They carry with them a confidence and an effortless looseness that translates into a successful clothing business, a love for surfing and surfboard design and the type of company they are out in the surf. Time and again, listening to them hoot as I drop into a wave, or laugh as I’m pitched over the falls, I’m reminded of the old maxim; the best surfer in the water is the one having the most fun. I suspect the same is true of design. And if so, you might want to keep an eye on Laurie and Gary Holmes.