First Published in

What makes Port Nolloth so special? Is it the barrenness, the quiet, the beauty? Is it the no-shopping-centre culture or the forbearing disposition of the people? I do not know. Neither did Jimmy du Toit and his blue-eyed wife Annelize, when they first arrived there 18 years ago.

The town of Port Nolloth lies on the Richtersveld Coast, 90km south of the Orange River mouth, on the Namibian border. In the 19th-century Namaqua copper was exported from the harbour, before Port Nolloth became known as the centre of the world’s gem-quality diamond deposits. The town is also legendary for its abundant West Coast rock lobster.

Nonetheless, it is for its colourful and cosmopolitan inhabitants that the town should be famous – a kaleidoscopic mix of races and cultures that have practiced harmony and tolerance long before it became the often-repeated mantra of a new and better South Africa. It is not because they have known prosperity or abundance but, more likely, because this mist-shrouded village has a calming effect on a person’s soul that makes hardship tolerable.

As such, Port Nolloth captivated the hearts and minds of the Du Toits, resulting in a project that is now capturing the hearts and minds of many others. The former lawyer and mathematical statistician are the drivers behind the KaiKai residential development, a public-private partnership with the Richtersveld Municipality.

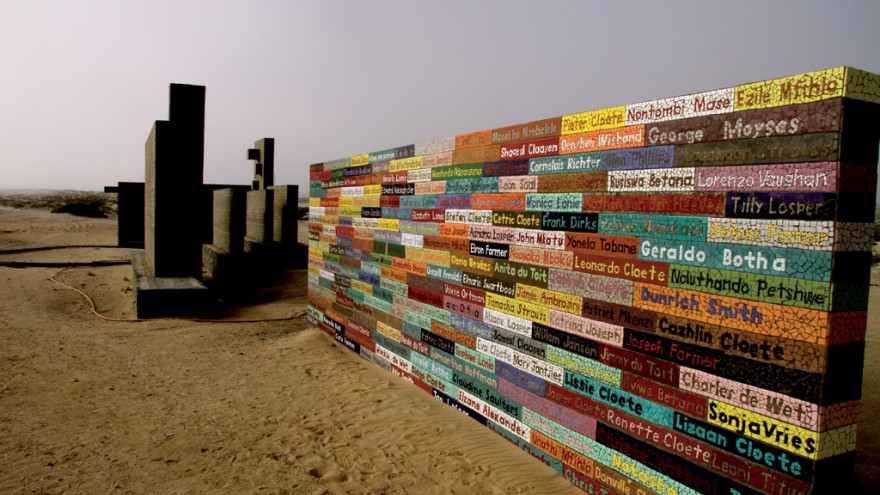

KaiKai is a residential development like no other. In the Nama language “kaikai” means “to cultivate, to elevate with praise or to nurture with pride” and the project aims for just such a perfect symbiosis between privileged property owners and the poverty-plagued local community. Lead by this principle, the magnificent centrepiece – the KaiKai Wall of Expression – is a piece of art. Instead of a forbidding and divisive structure that separates the rich from the poor and the good from bad, as demanded by a market with a neurotic obsession with safety and security, it is rather a symbol of hope and reconciliation, of sharing and of not doing unto others.

The community of Port Nolloth has become integral to the creation of this brick, mortar and mosaic installation. An artist from Johannesburg taught 16 members of the local community the art of mosaic at the outset of the project and these students have transferred their knowledge to their peers, with 65 local mosaic workers now employed permanently on the site.

The art is conceived, debated and created in the on-site KaiKai studio and then converted into exquisite and colourful mosaic pieces. These will eventually cover an almost 3km-long structure meandering over the dunes. KaiKai has created more than 80 sustainable jobs, all built on the living format of a monumental dream that is already recognised as a truly unique and remarkable South African community project – described by Elle Decoration (November 2009) as “the most beautiful wall in the world”.

Dreams, emotions, visions, thoughts and feelings are being tactilely transformed into a visual delight of texture and colour for the appreciation of the emphatic observer. The impudent miracles of the natural and supernatural are being expressed in thousands of fragments each individually formed by the hand of a Port Nolloth resident in accordance with the ancient mosaic tradition. And, as a tribute to the town and its people, 12 000 names are being painstakingly crafted in small quartzite and ceramic pieces – a monument of mosaicked humanity.

What has particularly astounded me about this project is the incredible talent that these artists possess, how they draw sketches that could have been done by Pippa Skotnes, Bettie Cilliers-Barnard or Walter Battiss. My conclusion is that in the blood of all South African people lies a primal core that, when left to act from the heart, results in an oeuvre that will include man in figure forms, incredibly close in essence to the shapes and forms that the San ancestors saw in their own time. Objects of inspiration include shells of mussels, abalone and the humble periwinkle; lichen growing on the rocks; colourful Namaqualand daisies; veld aloes; broken river reeds; collections of wind-battered driftwood; man; woman and child.

I asked Mervin Claasen, one of the local art designers, where he gets his inspiration. He replied: “Neil, it is like this, when I walk in the veld I see things. Sometimes I will pick a flower, I will take the leaves away and then I will open the centre with my fingers, and inside will be the heart of the flower. I will then sit down and draw what I see on paper. My sketches are then shown to the team and if they like what I have done, we will draw my idea on larger sheets. Finally we will add colour in the form of tiles; slowly cutting pieces to follow the lines of the picture, until eventually the mosaic sheet is ready to find a permanent exhibition space on the wall.”

In the artists’ notepads of inspiration I found the following word sketches: “man in search of his identity”; “surroundings and inheritance and how man translates dreams into vision”; “footsteps in time awaiting a human to fill them”; “procreation and humanity”; “the understanding of what is important” … all ideas of innocence, so simple and childlike in their humanity and humility.

To see this space is to believe that South Africa does have heroes who fulfil their dreams – dreams that can unite people with different cultural backgrounds to make this land a living legacy for future generations.

For more information: www.kaikai.co.za