Mais oui! As every French fifth-grade student knows, the Internet was invented in Paris. It was called Minitel, short for Médium interactif par numérisation d’information téléphonique, a network of almost nine million terminals that allowed people and organizations to connect to each other and exchange information in real time. Minitel boomed during the 1980s and 1990s, as it nurtured a variety of online apps that anticipated the global dot-com frenzy. It then fell into slow decline and was finally decommissioned after the “real” Internet rose to global dominance.

Both Minitel and the Internet were predicated on the creation of digital information networks. Their implementation strategies, however, differed enormously. Minitel was a top-down system; a major deployment effort launched by the French postal service and the national telecommunication operator. It functioned well, but its potential growth and innovation was necessarily limited by its rigid architecture and proprietary protocols.

The Internet, by contrast, evolved in a bottom-up way, managing to escape the telecommunication giants’ initial appeals for regulation. Ultimately, it became the chaotic but revolutionary world-changer that we know today (“a gift from God,” as Pope Francis recently put it).

Today, another technological revolution is looming. Pervasive digital networks are entering physical space, giving rise to the “Internet of Everything” – the networked lifeblood of the “smart city.” And, once again, a broad spectrum of implementation models is emerging in different parts of the world.

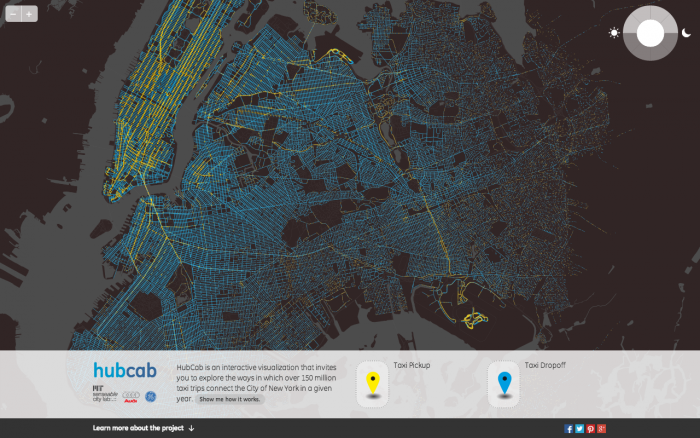

In the United States, the general idea of smart urban space has been central to the current generation of successful start-ups. One of the latest examples is Uber, a smartphone app that lets anyone call a cab or be a driver. The company’s operations are polarizing – Uber has been the subject of protests and strikes around the world (mainly in Europe) – yet it was recently valued at a stratospheric $18 billion.

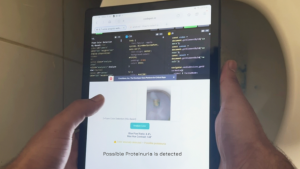

Beyond Uber, the learning thermostat Nest, the apartment-sharing website Airbnb, and the just-announced “home operating system” by Apple, to name just a few innovations, attest to the new frontiers of digital information when it inhabits physical space. Similar approaches now promise to revolutionize most aspects of urban life – from commuting to energy consumption to personal health – and are receiving eager support from venture capital funds.

In South America, Asia, and Europe, all levels of government are quickly identifying the potential benefits of building “smart” cities, and are working to unlock significant investment in that area. Rio de Janeiro is building capacity at its “Smart Operations” center; Singapore is about to embark in an ambitious “Smart Nation” effort; and Amsterdam recently channeled €60 million ($81 million) into a new urban innovation center called Amsterdam Metropolitan Solutions. The European Union’s Horizon 2020 program has earmarked €15 billion in 2014-2016 – a significant commitment of resources to the idea of smart cities, especially at a time of severe fiscal constraints.

But how can such funding be used most effectively? Indeed, is allocating huge sums of public money even the right way to stimulate the emergence of smart cities?

Government certainly has an important role to play in supporting academic research and promoting applications in fields that might be less appealing to venture capital – unglamorous but crucial domains, such as municipal waste or water services. The public sector can also promote the use of open platforms and standards in such projects, which would speed up adoption in cities worldwide (Barcelona’s “city protocol” initiative is a step in this direction).

But, most important, governments should use their funds to develop a bottom-up innovation ecosystem geared toward smart cities, similar to the one that is growing in the US. Policymakers must go beyond supporting traditional incubators by producing and nurturing the regulatory frameworks that allow innovations to thrive. Considering the legal hurdles that continuously plague applications like Uber or Airbnb, this level of support is sorely needed.

At the same time, governments should steer away from the temptation to play a more deterministic and top-down role. It is not their prerogative to decide what the next smart-city solution should be – or, worse, to use their citizens’ money to bolster the position of the technology multinationals that are now marketing themselves in this field. These companies’ ready-made, proprietary, and typically dull offerings represent a route that should be avoided at all costs – lest we wake up to find ourselves in Minitel City.

Carlo Ratti is a research professor at MIT, where he directs the Senseable City Laboratory. Matthew Claudel is a research fellow at the Senseable City Laboratory.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2014. www.project-syndicate.org