One of the most influential "non-musicians" and producers of all time, the father of modern ambient music, prominent anti-war campaigner, influential art theorist and prolific visual artist, the inimitable Brian Eno was in Cape Town in February. He spoke at the Michaelis School of Fine Art, where he was exhibiting his 77 Million Paintings installation, and a few days later at the Design Indaba Conference.

Brian Peter George St John le Baptiste de la Salle Eno was born in Suffolk on 15 May 1948. His father, a postman, would come home from work so tired that he would fall asleep at the table into his dinner. Young Brian swore that he would never get a job and decided to dedicate himself to art.

At the age of 17, his girlfriend's mother, a scientist and intellectual mentor, could not understand why someone with as good brain as Eno possessed would want to "waste it on art". Not to be discouraged, Eno began to engage more critically with the why and how of art. By his early 20s, he had "lost faith" in painting and began experimenting with other media. It was at this time that he decided to focus on music, the beginning of a career that would fund his concurrent endeavours in the visual arts. Since the late 1970s, Eno has been experimenting with the medium of television, specifically the transmission of light rather than of information.

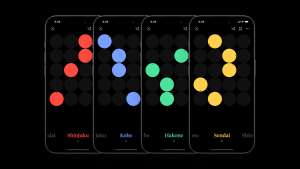

During the 1990s, Eno became increasingly interested in self-generating systems. Generative Art, he calls it, allows an artwork to take on a life of its own. Generative Music, for example, blends several independent musical tracks in such a way that the listener could hear an almost infinite array of permutations. Eno soon realised that he had hit on a new cultural nerve. Today the idea has spread to graphic arts, design and beyond.

The success of Generative Art contradicts the common assumption that our collective attention span is diminishing. The work has the power to hypnotise people, who sit down and stay for sometimes hours. It also challenges the notion that the artist must be in control. Here the artist can accept and enjoy not knowing where the artwork is going, just like the audience. The artist's input simply sets the trajectory for the work to evolve beyond the control of the artist, a kind of pre-programmed improvisation. And because the simultaneous soundtracks are not synchronised or coordinated, it challenges the assumption that syncopation is a necessary feature of music. Above all, there is no direction, no beginning or end. There is nothing to tell the audience what is going on, what sort of experience they should be having, whether they "get it" or not.

Combining generative art and music, Eno has taken his 77 Million Paintings installation around the world. Visually, a flower-like constellation of TV screens that always contain three different slides prepared by Eno, which slowly morph into new ones. Musically, six CD players each play one "horizontal layer" of the soundtrack. Each CD is a different length, with a different number of tracks, and set to random shuffle. It would take 9000 years to view every combination of audio and visual.

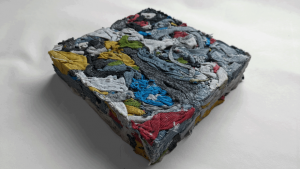

Late in 2006, Eno released a software/DVD/booklet package of 77 Million Paintings, which allows buyers to take the installation into their own home. 10 000 were made and quickly sold out. In doing so, he managed to make a conceptual installation commercially viable, making it accessible and commercially viable, exporting it into the homes of willing consumers.

David Bowie once stated that Eno was always "very aware of breaking down the barriers between high and low art". Three and a half decades ago, Eno was a glam icon, in the words of rock writer Barney Hoskyns, a "cross-dressing Lothario" who was "one of the era's most whimsical stars". For Hoskyns, Roxy Music, under the influence of Eno, bridged "the gap between progressive art rock and disposable teen pop", understanding the radical implications of "taking the avant-garde into the high street."

And now that the avant-garde has been taken out of where it used to be, can we still say that the avant-garde still exists as a viable concept? Eno is doubtful. To him, it brings him back to the notion of fine art as separate. The avant-garde was for some reason always reserved for fine art. Today, though, Eno argues, "fine art" is not better or above or even separate from craft, design or popular art, for example.

Eno sees any distinction between high and low art as an archaic, pre-Darwinian notion. Darwin helped us to realise that all living things are related through evolution. In so going he gave us one language to speak about these things, something that is still lacking in discussions of arts and culture.

For Eno, the fundamental questions are never asked or discussed: what is art? And what is it for? He lambastes the standard of writing by artists today, calling for more rigour in the field – for artists to be able to explain themselves in a way that others can understand. Ultimately, he says, a new theory of art is required to explain what art is and why we make it, to help explain all human cultural behaviour.

Searching for answers at the Design Indaba a few days later, Eno presented a simple slideshow – a painting, a vase, a motorbike, a pair of spectacles, an ornate knife, garden gnomes, a female body builder "sculptor", boyband posing, a woman in underwear and a Shitzu. What's art, and what's not? All of these items have aesthetic and functional traits. But can art objects be functional, and can functional objects be considered art? Eno's answer would be yes.

Having opened it all up, Eno arrives at an umbrella definition that does not seek to rank art in order of importance. Art can be simply understood as "everything which we don't have to do," everything possessing a "stylistic overlay" beyond functional necessity.

And what happens when we engage with an art object? Eno uses the concept of multi-dimensional spaces: when we engage with anything, we consider a complex variety of things. To illustrate, a cultural object that we all share – a haircut. Possible axes include masculine to feminine; rebellious to conformist; retro to futurist; organic to synthetic; etc. All of these values are not absolute but relative and constantly changing. Like a haircut, every art object is a manifestation of a location in a multi-dimensional cultural space, and an invitation into that space.

Eno's bold new theory of art moves beyond cultural theorist Pierre Bourdieu by eliminating rather than explaining the barriers between high and low art, or in Bourdieu's terms, the centre and the margins of the field of cultural and artistic production.

We "do" art not only because we're good at it, Eno tells us, but more importantly, because we're constantly monitoring difference, or history. Art, like language, enables humans to cooperate and communicate in large groups. Art is thus a way of staying in tune with one another. And art is like a simulator – you can surrender to it because it is safe. An exhibition like 77 Million Paintings is proof of this. Art is therefore also a way of commonly testing other realities.

And with that, his time is up. Mr Eno is presented with a medal and sent on his way, probably a little miffed at having been flown to the other end of the world to deliver one of the final talks of a three-day Design Indaba and then have to skim over his notes in double-quick time. But for those lucky enough to see him, his visit was a welcome and refreshing injection of clarity from one who, despite an intimidating track-record, comes across as approachable, humble and passionate about his work, which shows that creativity can stem from unlikely sources, in this case a profoundly simple, yet sophisticated, near-mathematical approach to music and art.