From the Series

Formerly Brooklyn-based, video artist and filmmaker Zina Saro-Wiwa relocated to Port Harcourt, Nigeria in 2013 to launch a new gallery space, The Boys' Quarters, in May this year.

The title of the venue is significant. “The Boys’ Quarters is the colloquial name given to the servants’ quarters,” Saro-Wiwa explains. “It’s a post-colonial hangover and an ever-present feature of West African life. The place where, to this day, servants and sometimes extended family members live.”

Equally significant is the geographical location. “I knew I wanted to engage with the Niger Delta,” she says, “and relocating as an artist, and not just visiting a family member, was the only way I was going to survive the onslaught of history and family and political realities. Being an artist allows you to respond to and shape what you experience.”

The fact that her father – the late environmental activist, writer and television producer Ken Saro-Wiwa – was killed campaigning against the ongoing oil damage within the region, leaves an historical footprint for her family, so housing the gallery in his old office is a powerful curatorial decision.

However, using his former workspace wasn’t her original plan.

She’d initially wanted to create a gallery within the actual boys' quarters behind her family's home, but “they balked at the idea and suggested that I do it in my father’s old office”.

There’s a definite social statement in this symbolic choice of name and venue, as visitors and artists are forced to say they are "going to the boys’ quarters’" to learn and experience something new. “It’s an intervention via language as well,” Saro-Wiwa states.

It forces people to place an alternative value on the servants' quarters, which is something Nigerians are not used to.

"Everyone wants to escape that condition. As a result the masses are not catered to. It is all about the ultra elite.”

There’s a strong sense of Saro-Wiwa honouring her father’s legacy by using the gallery to try to change the script about the Delta region. She’s noted that even a google image search of the Niger Delta brings up overtly political images. These tend to be well-documented visions of oil spills, gas flares and decimated landscapes.

Essentially bored by politics, her creative motivation has far more to do with “building the region's cultural muscle”.

She sees art as an alternative and freer way to explore ideas, so what she’s produced on the second floor of the white-fronted building is a simple space with an interior that makes a strong point that imported materials, particularly the tacky tchotchke items that are sold as objects of desire in Nigeria, are not necessarily better.

Saro-Wiwa has purposefully used the white cube as a format. “The idea of a simple, basic, concrete white cube as a place to show art in the Niger Delta seemed like a good idea given the way art is often shown in that part of the world,” she says.

In Nigeria art is normally highly commercial, and shown in hired spaces such as hotels, event spaces or oil company head-quarters.

"I wanted a more raw space in a truly public place that allowed the art to do its work of telling stories and asking questions.”

To her, the space is like “a magic box” whereby “anything you put in it has to be reconsidered”.

Her design choices, such as the simple painted concrete floor in the gallery reading room, are also important within a directly local context. “It’s bright yellow and has had quite an impact, but not just because of the colour. It reminded certain visitors of how their parents or grandparents used to paint their floors before marble tiles or linoleum were the rage.”

Saro-Wiwa also takes great pride in the gallery’s bottle-top bathroom floor laid by the caretaker who also made artwork that sits within the space. “I love the fact that the gallery is helping create artists. My site manager, Felix, is becoming an amazing photographer.” The nod to thinking about her environment differently also stretches to Saro-Wiwa’s take on African food culture.

She has a blog called Food Is Ready and caters the openings for the exhibitions with re-imagined local recipes.

Petroleum has always been seen as the most important thing to come out of the ground, she says, but now agriculture and thinking about the land differently is something that needs addressing.

It’s this simplicity and the beauty within Nigeria that Saro-Wiwa is keen to show. An artist herself, she acts mainly as curator in this space although she has made work for the venue.

The installations that appear in the Windowall Gallery, which is the wall that was formerly a window in her father’s old office, have so far been made by her. “I made a video piece in response to the first featured artist Perrin Oglafa’s work,” she says. “It’s called 'An Odoni Heart'.”

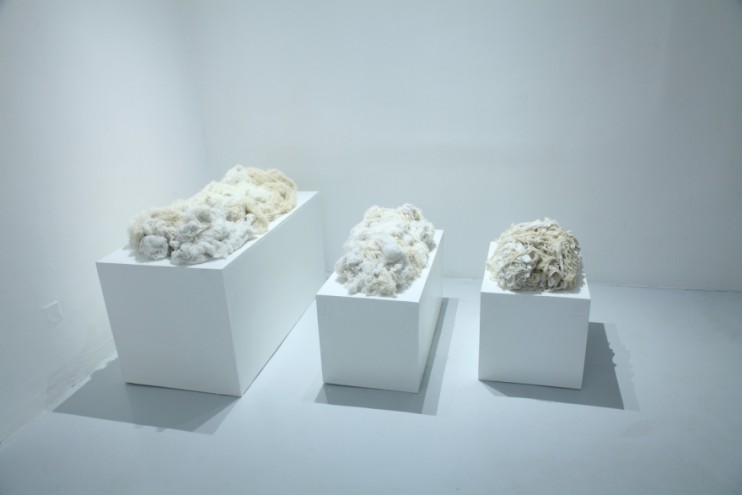

Oglafa is one of three local artists who have been shown at the gallery since its opening, Segun Aiyesan and Johnson Uwadinma being the other two.

There is a fourth name that Saro-Wiwa is also keen to mention – Tony Akudinobi. “He made the incredible furniture in the reading room. All his pieces tell a story.”

She is also developing plans to have Boys’ Quarters pop-ups and exhibitions in galleries and museums around the world from 2016.

Of course, there is a strong desire to see more women artists from Nigeria, Africa and abroad come through the space, as well as more video art. “To expose the Niger Delta to alternative forms of art making will be exciting for me,” she says, “but we have only just begun and I really want to use the space in a way that is not just inventive for the Niger Delta, but inventive period.”

The Boys' Quarters opens a new show of work, "Erasure", by artist Johnson Uwadinma on Saturday 13 December 2014 to 21 February 2015. www.boysquartersprojectspace.com

Nana Ocran writes about contemporary African popular culture for international publications including Virgin Atlantic, Wings Magazine, Selamta Magazine and S14. She is also a Pan African trends watcher for Paris-based think tank Breakthrough Innovation Group (B.I.G.).