“Comics is storytelling, comics is acting, comics is writing – everything. Comics is not just drawing,” says Mohammed El-Seht of Cairo-based cartoon duo Twins Cartoon.

Before 2008, comic artists and street artists in Cairo were underground. When the political revolution took hold, emboldening the people of Egypt, creatives came out in droves despite the threat of censorship and violence from the government and a conservative public.

Mohammed explained it best at the Design Indaba Festival in 2016 when he said, “We won way of how to (sic) express our rights through demonstration against authority but not just through demonstration. It wasn’t just a political revolution, it was also an artistic revolution. This is reflected in the art scene of Egypt.”

But now, over a year since their appearance at Design Indaba, the disillusionment is palpable.

When we meet up with the twin cartoonists, Mohammed and Haitham, we’re in the first leg of a two country visit to North Africa to uncover how design, creativity and innovation is used to build a better world.

As part of the journey we documented stories from people like 25-year-old designer Amna Elshandaweely who uses her Africa-inspired garments to bridge the gap between African identity and Middle Eastern identity, an awkward middleground held by many Egyptians.

We met Dina Amin, a tinkerer who builds machines using junk and promotes them using stop animation – Egypt is one of the most polluted countries in the world.

We also spent time in the historic Downtown Cairo with Omar Nagati, an architect and activist who believes Cairo’s informal architecture is as much a part of the livelihood of the city as big-budget urban developments.

With each of them, we see the limit to what a political revolution on its own can accomplish and the struggle to keep forging ahead despite feeling deflated.

“Actually, after the revolution, many people started to make comics, graffiti and photography. They started to feel like everything is for us, we own the street we own the comic magazine, we own everything,” explains Mohammed.

“But it was fake, maybe the revolution was real, but what they feel was fake because the revolution can’t change everything. It can be a good tool to keep going and struggling. From my point of view, we still have more and more [work to do].”

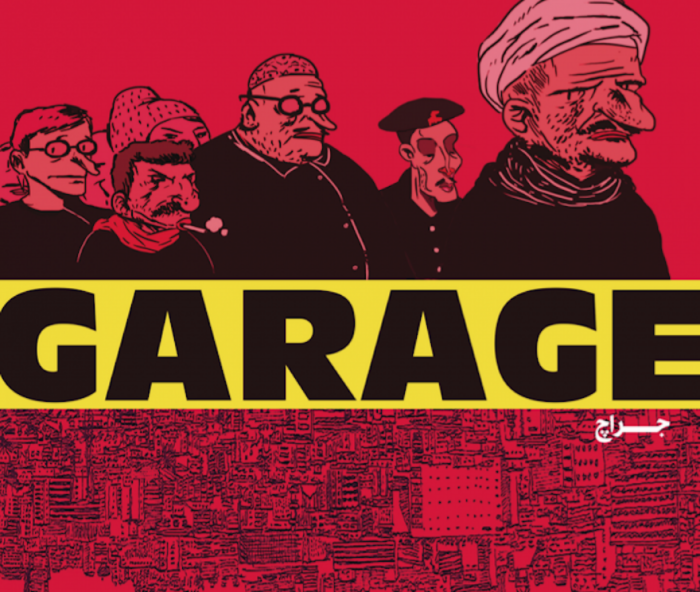

Their work did indeed begin in earnest after the Arab Spring. Following in the footsteps of other Egyptian pop-literary comics magazines like Toktok and Shakmagia, Mohammed and Haithem launched Garage Magazine in 2015, a comic book collective and publication.

They also co-founded the CairoComix Festival in the same year and have since been involved in numerous international comic book projects including the first English edition of Garage Magazine with Design Indaba, which was launched in 2016.

Their work is humorous, vibrant and reflective of traditional Arabic dialect, making it relatable to the everyday Egyptian. And as for their subject matter, the two seem wearied by politics.

There is more to Egypt than sexual harassment and a failed revolution, they tell me as we weave our bodies between cars in the frenetic Tahrir Square.

Mohammed and Haithem lead us to a street cafe in a back alley and we settle alongside the locals who are still drinking, eating and smoking hookah even though it’s 12am on a Tuesday. The streets only begin to empty around 2am in Cairo, they explain.

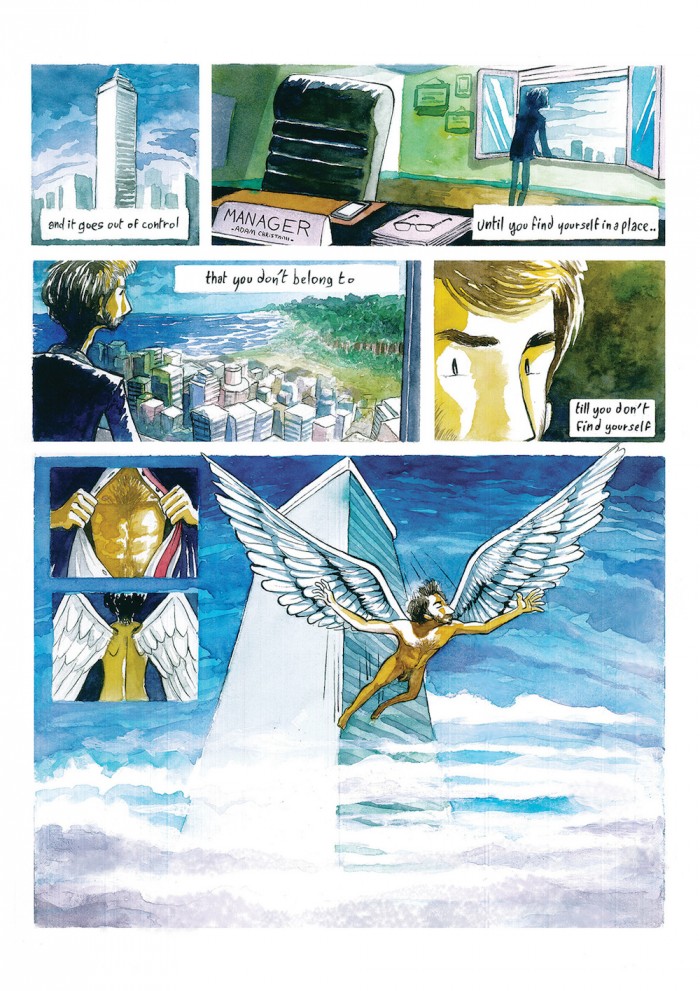

To me, the city seems to always be in a frenzy, with the day’s gridlock often indistinguishable from the nightlife. One of their artists, Farid Nagy captures this feverish energy in New Adam, a short comic included in the first edition of Garage that looks at a man who leaves an idyllic life for the city.

Initially, he falls for the fast food, fast cars and quick money but soon he loses interest, finding that lifestyle unfulfilling. In another of Nagy’s shorts, Bubble, he tells the story of people who are inattentive to the problems facing the underprivileged until those problems begin affecting them.

“We live in Cairo; it’s a very crowded city and it has its own social problems,” says Nagy when we speak to him the next day. “It’s good inspiration. There is a lot of problems such as the crowded places and sexual harassment even political problems.”

Themes like the city, relationships, politics and identity are all part of Garage Magazine’s offering largely because Mohammed and Haithem allow their comics to interpret a theme as they please.

“We give the artists the freedom to do what they want to do because it’s not a dictatorship,” says Mohammed. Haithem adds: “It’s without censorship. It’s important for us to do without censorship.”

Censorship is still a growing concern in Egypt with the country banning scores of websites in a recent crackdown on private media. This recent push to curb dissent makes art collectives like Garage even more valuable as they take aim at not only an oppressive regime but at the people, asking them to challenge their own beliefs about daily life in Egypt.

“I don’t have a fear of the regime or the government,” says Mohammed. “I always have a fear of the people, the public, because many of them are not employed and don’t have an education. So if you make something they don’t like, something out of the box, something they are not used to having, they just come and make censorship by themselves.”