First Published in

As a child, you’re made to think that patterns are decorative drawings that add colour and a bit of spunk to your already abstract creations. Gradually, these patterns begin to translate into everyday life from the kind of clothing you wear to the layout of your home. Patterns cease to be simply decorative and begin to take on the characteristics of those who engage with them.

For pattern designers Renée Rossouw and Laduma Ngxokolo, patterns are a delicate balance between what is beautiful and decorative, as well as being a fragmented expression of their identities. These patterns may act as tools in the composition of their products, but they simultaneously create a conversation between the formal nature on which the pattern exists and what the pattern can be interpreted to represent.

A pattern isn’t only definable by the way it looks, but also by the way it acts and the sentiment it’s able to carry through it. Having graduated with a Masters in Architecture and gone on to complete the RSP Masters at the European Designer Labs in Madrid, Rossouw puts her obsession with patterns down to her extensive travels.

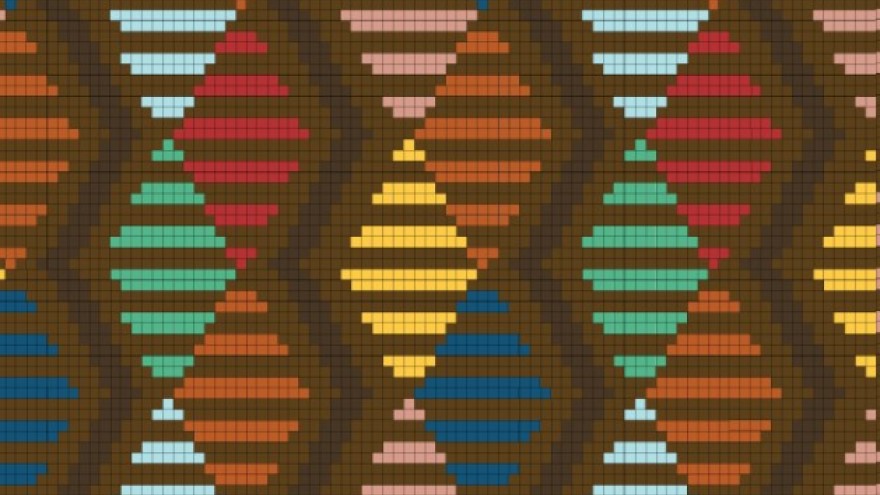

Sitting in her small studio, she chooses her words carefully when asked what makes a pattern exactly that. “A pattern is a graphic, but it is about repetition, rhythm and harmony. It’s as much about negative space as it is about positive space. It’s about seeing something obvious in new and experimental ways that lends an interpretive element to the end result,” she explains.

Ngxokolo discovered his obsession with pattern design at Lawson Brown High School. His designs earned him a bursary to Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University and first prize at the South Africa Society of Dyers and Colourists Design Competition in London last year.

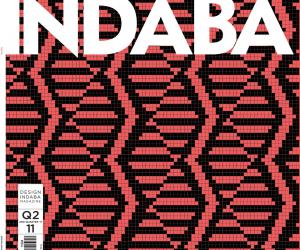

Cautious in wording his ideas about patterns, Ngxokolo is fascinated with the interaction between colour and space, as well as a pattern’s technical properties. Deliberating, he says: “While colour, rhythm and style are important to me when designing a pattern, it is the ability to attach an identity of a certain group, culture or subculture to a pattern that takes a pattern beyond a decorative nature.”

But both agree that a pattern cannot be designed just for the sake of itself. “If you want to design a good pattern, you can’t just copy and paste. Patterns are graphics in harmony and they take time,” says Rossouw. Patterns aren’t born out of the need to create them, but evolve tangentially out of a continually effervescent imagination coaxed by fortuitous inspiration.

Designing a pattern is a highly intuitive process, Ngxokolo agrees. He knows something is pattern potential when he’s able to look at what inspires him and it speaks to him, revealing its distinctive nuances, its visual relevance to the environment and a modern-day novelty.

Speaking of patterns actually “speaking”, it would seem that they have a voice of their own, telling their designer precisely what would suit them, according to Rossouw. At first she seemed a zig short of a zag or even a dot missing its polka relatives, but she is as sound of mind as any designer of abstracts can be.

“A pattern will tell you were it wants go and where it will work,” says Rossouw. The nature of the pattern will always influence the object to which it is applied because once the entire range of products is complete, Rossouw continues, a certain dialogue should exist between each pattern allowing everything to come together in one absolute, yet vaguely displaced identity.

Ngxokolo’s patterned knitwear range in particular emphasises this dialogue between pattern, its canvas and the significance of identity. His knitwear jerseys were inspired by the need for Xhosa-culture initiates to wear clothing that was more representative of their culture once they had completed their initiation ceremony.

“When a boy is initiated into manhood, they are required to burn all their old belongings and buy new possessions to show that they have made this transition,” explains Ngxokolo. “But Pringle was just about the only choice in high quality men’s knitwear and I felt that the clothing should show their heritage proudly and be more culturally relevant and authentic.” His patterns draw inspiration from traditional Xhosa beadwork motifs and other African cultures. Nonetheless, he is also aware that while ethnicity is the foundation for his patterns, his designs should also contain a more modern flair in order to appeal to the increasingly fashionable youth.

When asked where they see pattern design in South Africa, Ngxokolo says that he is in a continuous argument with himself regarding what it means to be a pattern designer, not just in South Africa but globally. If a fashion designer takes a patterned fabric and designs an outfit that is seen by millions, the pattern will still dominate the outfit and Ngxokolo finds himself asking the question of who is the real designer? “There needs to be a lot more money invested into pattern design as it is a vital part in a number of design sectors from fashion and textiles to homeware, decor and jewellery,” he says.

“The potential for pattern designers in South Africa is pretty much unlimited,” says Rossouw. “Inspiration can be found just about anywhere and we have so much here that they don’t have in other countries allowing us to be original instead of producing what has already been done.”