Mixed-media artist Kip Omolade, who was born in New York City, started out as a graffiti artist when he interned at Marvel Comics and The Center for African Art. In a sense, it set the stage for his current work – larger-than-life portraits in bold, saturated, attention-grabbing colour. Design Indaba asked Omolade about his latest Diovadiova Chrome series, the influence of his Nigerian heritage, and what it means to fight for humanity through creativity.

You have been working with masks and the human face for some years now. What are you searching for in your most recent work, and are your processes much the same or different? Can you tell us a little bit more about how you work?

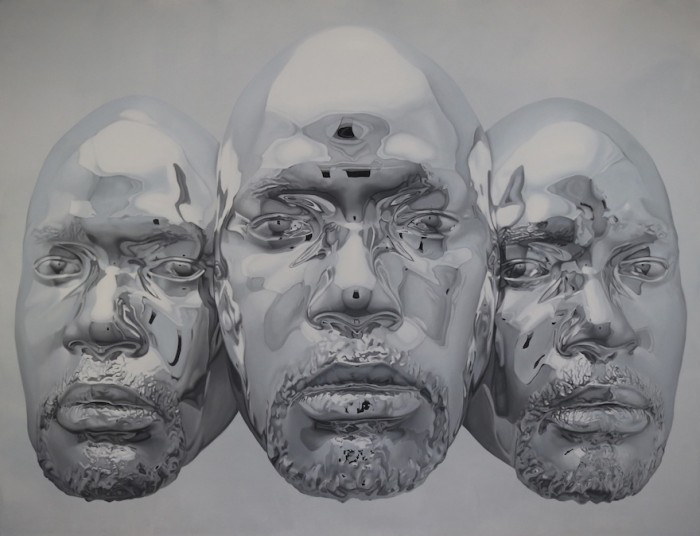

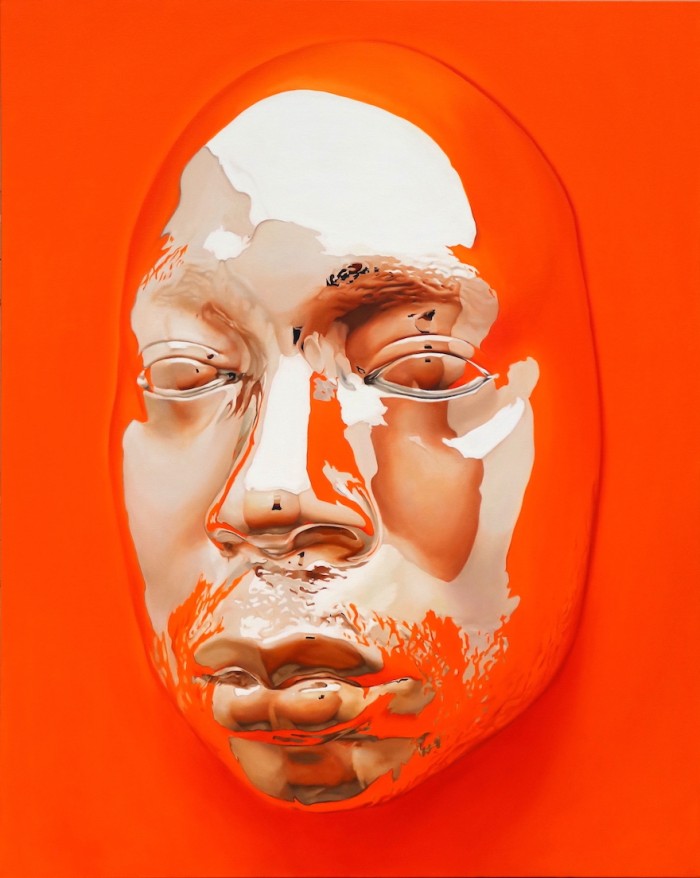

With Diovadiova Chrome, the process involved making moulds and casts of my models’ faces to make chrome masks. I photographed the masks in different locales to serve as photo references for the portraits. In the reflections of my new painting “Diovadiova Chrome Kitty Cash XIV” images of skulls are used to represent death as a commentary on mortality.

With my new GOD BODY series, I’m examining divinity and the Black woman’s body. In the oil paintings, an African American woman in a latex bodysuit is positioned against words. The words in the paintings (“I AM GOD”, “GOD BODY”, “BODY”), reference religion and contemporary culture.

The white latex bodysuit also references ancient Greek marble sculptures of supposed idealised human forms. The use of a superhero-like figure with lettering recalls my teenage years as a Marvel Comics intern and NYC graffiti writer.

Using letters as art is also similar to the works of pop artists like Robert Indiana, and Ed Ruscha. However, as an African American artist, it is important to feature text and the Black body itself as a strong graphic design. This idea was exemplified by the New York Times writer Wesley Morris, who described a Beyoncé and Jay-Z video performance at The Louvre as “representational vandalism: the black body as physical graffiti”.

From civil rights protest signs of the 1960’s like “I AM A MAN” to today’s “Black Lives Matter” iconography, African Americans have used language to target injustice and speak truth to power. Adding a human figure that interacts with important words has a profound effect. The Black woman’s body in my work adds additional context, supports the intent of the words, and sometimes confronts the meaning. Joyce, my sister-in-law, and mother of two, has posed for all of the current GOD BODY paintings. In my recent ten-foot-tall painting titled “I AM GOD”, two “Joyces” confront each other over who is relaying the message.

Diovadiova Chrome and GOD BODY use futuristic, shiny surfaces against bright, saturated colours. In both series I use representations of African Americans to examine universal human themes such as love, beauty, faith, death, immortality, and identity.

You've said your connection to Africa means everything to you. Why the connection to Ife sculptures in particular, and how do you see your work in relation to this historical tradition? What do masks mean in a modern context?

Ever since I was a child, I would see reproductions of traditional Ife masks in textbooks and magazines and feel a sense of pride. The masks were made from a “lost wax” technique that involved making moulds and casts to make shiny sculptures that were used in rituals. I share both the technique and the representations of deities, but I use more contemporary aesthetics and concepts.

By now, most of us are used to wearing masks due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Initially, my Diovadiova Chrome masks were used to show how we present the best versions of ourselves, but now they can also serve as symbols of protection.

The theme of deity is prominent in your work – what does it mean to you, and what elements of worship do you think come across most strongly?

I’m interested in how iconography can be used to show the relationship between spirituality and humanity. Many religions base their faith systems on the idea that the divine can exist in human form. How that is represented is based on the art, technological advances, and beliefs of a culture.

With Diovadiova Chrome and GOD BODY, I’m showing how humans can be a part of God not apart from God. If people from different faiths can see the divine in each other there would be less war and destruction. My art is about the fight for humanity.

Your colour palette is so striking. What has drawn you to these bright, saturated colours, and to chrome? You've spoken about the brightness of graffiti and the need for art to fight for attention, in a sense, but the scale of your work alone means it already has presence and gravitas. Why this particular colour palette?

I feel the potency of colour when I design a painting. Something happens on a spiritual, visceral level when I connect with a particular colour. I see colour as readymade art. I often use the oil paint fresh out the tube. I don’t have to add anything to the colour, I just have to find ways of incorporating the raw colour into my painting. Applying layers on layers intensifies the impact of the colour even further.

I’m always looking for the highest level of intensity to express myself and connect with the viewer. This comes from the universal human triggers of scale, light, shiny surfaces, the face (and now the female form), and colour.

Read more:

Nigerian artist Victor Ehikhamenor explores the responsibility of the African artist.

Nigerian artist Dennis Osadebe on isolation, the future and African art.

Graffiti increased the property value in this Miami neighbourhood.

Credits: Kip Omolade