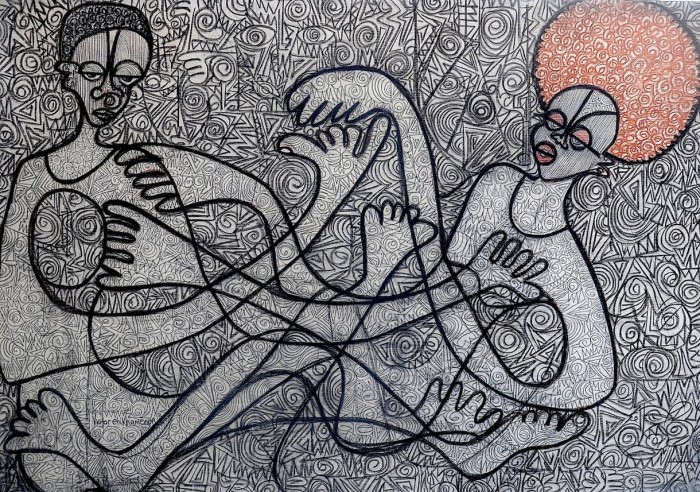

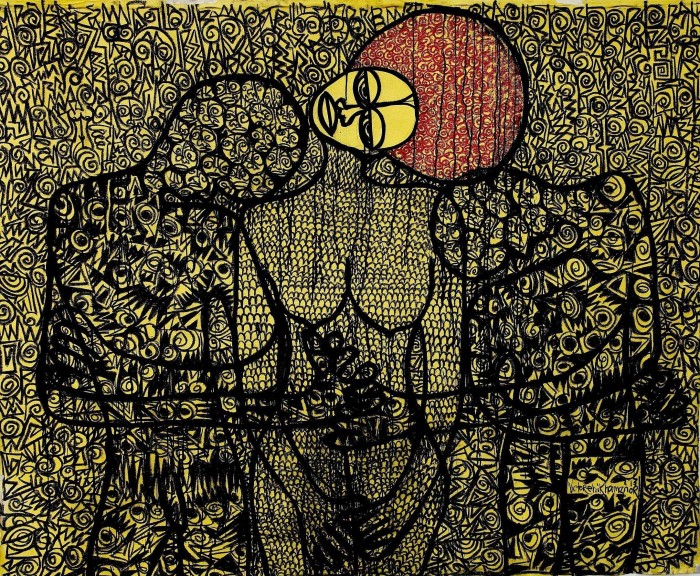

Victor Ehikhamenor’s work is all-consuming: it draws you in, and, in a manner of speaking, spins you around and spits you out, leaving you to question all that you thought you knew. The hypnotising lines and curves of Ehikhamenor’s work came from his hands at an early age.

“Between the ages of four and five I drew obsessively- just drawing lines. I never stopped. I grew up in the village, so we didn’t have art teachers, so this was all me, just doing this stuff by myself,” says Ehikhamenor .

At this age Ehikhamenor was unaware of what an artist was or what creating art even meant. It took a family friend, gazing upon his work, and stating, “Oh, you’re an artist”, before he realised the potential of his work.

“My brother’s friend called me an artist one day. Confused, I asked, “What is that?” He responded, “It’s what you’re doing.” "I was like OK, I’m an artist.” So I would write on my notebooks and on everything: My name is Victor, aka artist,” says Ehikhamenor, laughing as we sit for lunch at a hotel in Kigali where we're being hosted on the 25th anniversary of the country's genocide.

Being a working artist wasn’t always possible for Ehikhamenor. Growing up in a small village in Nigeria, he had little exposure to art education. He mentions that looking back at his childhood, he now can see that he grew up in a very artistic home.

Being an artist was encouraged and supported by his family. But he realised that only creating art wasn’t always going to pay the bills. Ehikhamenor’s father sent him to further his education and looking for the closest thing to art, Ehikhamenor found himself in the lecture theatres of the English and literature department.

“I fell in love with storytelling. I would often write letters for old women who wished to communicate with their families in the city. Because of this new venture, my focus shifted a little bit from art making to writing,” says Ehikhamenor.

Writing for major publications such as the New York Times and The Guardian was great, but Ehikhamenor still wanted to become an artist. His art and writing were still not paying the bills and he was struggling.

“I knew what kind of artist I wanted to be right from day one. I could immediately differentiate what different types of art were, and I realised that I wanted to be an institutional artist, not just making stuff and just selling for the sake of selling,” says Ehikhamenor.

While going back to studying and working in IT, Ehikhamenor continued to create his works of art. He may have been qualified in IT, but he clearly states, “I won’t tell you that I am an IT person, I will tell you that I am an artist first.”

Today Ehikhamenor is based in Lagos, Nigeria. His return to his home country began with a feeling of restlessness that he could not get rid of while living in the western world. When he returned, he held an exhibition of his work, and put his feelers out for how the country would respond to his art. By the end of the exhibition 90% of his work had been sold. It was then that he knew that he had made the right decision.

Ehikhamenor’s art has travelled across continents and has been exhibited in some of the most prestigious galleries and museums around the world, including the first Nigerian pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale. One of his works can also be seen at the Norval Foundation's sculpture garden in Cape Town (below).

Speaking about the kinds of things that inspire him and his work, he always finds himself going back to his simple beginnings. “When I get to a place and I’m asked to create artwork, I have to 'consume' the place first. I go to the villages. I like going to the villages - I grew up there. There’s so much that a village can tell you,” he says.

Ehikhamenor looks for the things that resonate most with the people of a particular area. He refers to the Rwandan landscape that we've been travelling over the past few days, and mentions that the straw fences used by the communities in the rural areas was something that drew his attention.

Seeing the intricate designs and weaving techniques, he noted that if he did an art installation in Kigali, it would be something as commonplace as that, and that he would place these straw fences in a museum.

“I would move something like that to the city, to a place where you would least expect it. President [Paul] Kagame has probably seen something like that without taking note. But if I bring it to the national museum, he would stop and take note of what has been done,” says Ehikhamenor.

He says that was the type of thing that would force those in power to take note of the art coming out of their country, and perhaps motivate them to invest in the arts. He wants art to generate a conversation, and to ask questions that others are afraid to ask. He wants it to be confrontational if necessary.

One of Ehikhamenor’s exhibits shines a light on the environmental degradation that has occurred as a result of capitalism and the greed of the human race. One of his artworks is a dripping oil drum suspended over a trough of water, which Ehikhamenor uses to comment on the oil industry of Nigeria, and the amount of pollution that it has caused in the country.

The artist feels that his work has been shifting more towards using his art for activism, and to uplift his community. He believes that the development of the African continent lies in the hands of the African people. He is of the opninion that relying on outside help only leads to major corporations stealing from the continent, or making a mess of the natural environment.

This is why he started his studio/residency, Angels and Muses. The residency offers two artists a space to create their art, host book readings, workshops, film screenings as well as press conferences. Completely self-funded, Angels and Muses is an open space, where artists can receive free mentorship from Ehikhamenor. The studio itself is a work of art, and has been featured on Netflix’s Amazing Interiors.

Ehikhamenor’s latest exhibition, Daydream Esoterica, recently took place in Lagos. The exhibition is described by critics as being an invitation into the inexhaustible mind of one of Nigeria’s finest artists. It deals with how the city of Lagos entices the artist to dream big, but at the same time it feeds off the frustrations of the artist. According to Ehikhanmenor, in order to survive, one must continue to daydream.

Read more:

Nigerian photographer's romantic visions of Lagos

Nigerian artist uses posters to tackle issues of climate change