Migration is part of being human. Wherever we may find ourselves in the world, somewhere in our history lies the story of moving to another place – for a variety of different reasons.

Migration decorates family trees, gives birth to stories, provides colour to our world, lies entrenched in our collective memories. Preserving these memories is essential and meaningful, but this is not always easy: as migration is often a traumatic experience, especially for those doing so because they are under threat.

In a time where global leaders are calling for borders, bans and bombs, the concepts of migration and refuge are constantly in the news.

This, together with a personal sense of responsibility to learn and tell these stories, is what inspired the work of the Foundland Collective. It was founded in 2009 by Syrian Ghalia Elsrakbi and South African Lauren Alexander, and operates between Amsterdam and Cairo. Their story in itself is steeped in migration. Elsrakbi was born in Damascus and later moved to Cairo. It was during their studies at Sandberg Institute in Amsterdam that the pair first met.

The real stories behind the news

After the 2011 Syrian Uprising, they became more interested in issues surrounding politics in the Middle East. They were particularly interested in portraying alternative narratives to those found in the mainstream world media.

They have achieved this by gathering information, and presenting it using a combination of visual arts including photography, graphic design, film and installations. While they’re an art collective, essentially the core of what they do is research.

Like their art, their research is drawn from a myriad of sources, from personal experiences to official archives, audio recordings and qualitative analyses of visuals.

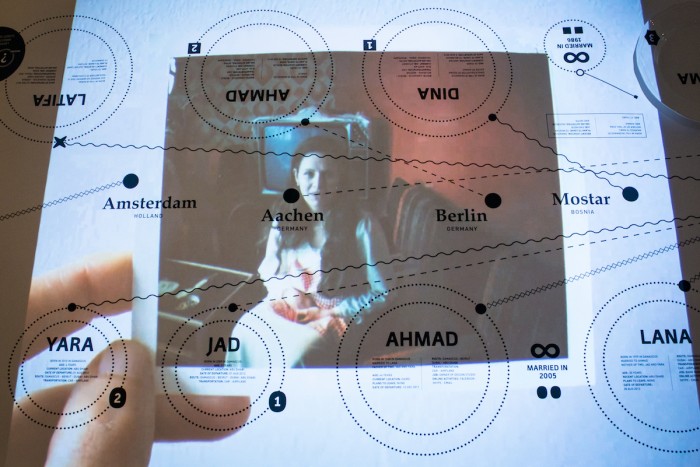

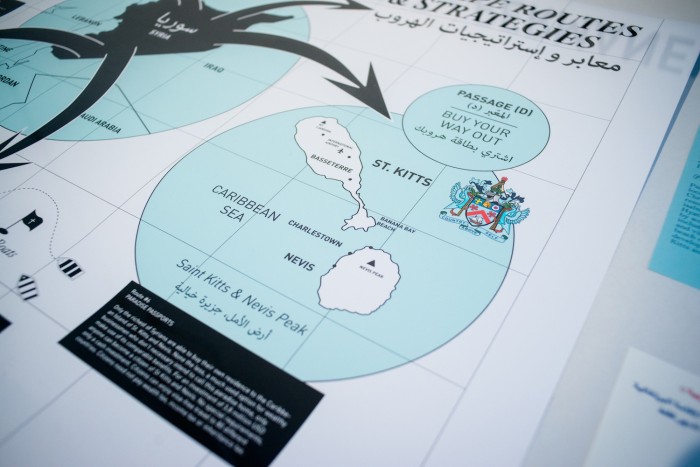

Their 2014 exhibition titled Escape Routes and Freedom Mirages, which they describe as a documentation of migration, had as its central feature a table depicting the stories of families who have fled from Syria. Named "Friday Table" it is an installation that visually maps one family’s migration. It’s inspired by Elsrakbi’s own family tradition of Friday night dinners, and depicts the seats of various family members – and where in the world they fled to or went.

Privilege affects refugee experience

Those destinations focused the pair's attention on another area of interest, namely privilege and access.

“If you have access to more money you can move to places such as Dubai, but if you don’t, your only option is to go to the camp,” says Alexander. It becomes clear that the crisis of forced movement can mean very different things to different families.

This installation also shows that only four family members remained in Syria when the installation was put together in 2014.

This is just one example of the ways Foundland is telling the human stories behind the headlines. “This is a way of using different levels of information graphics to communicate a more personal story. This is what we’re really interested in,” says Alexander.

Remembering the house in which you grew up

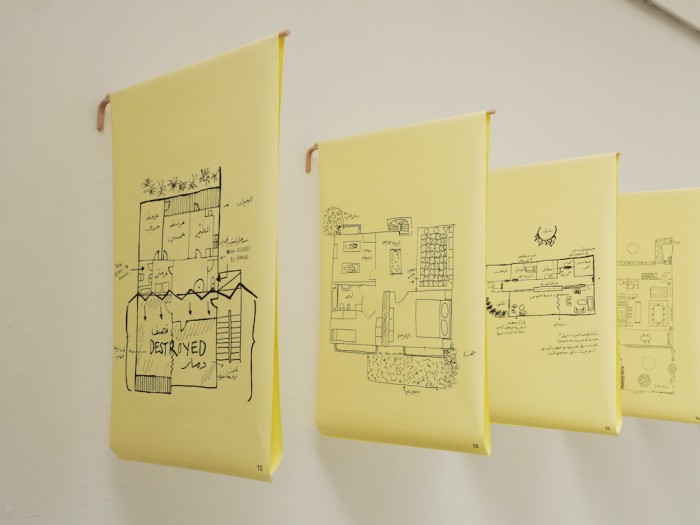

Another poignant personal depiction of the Syrian story is the Groundplan Drawings. The concept is simple, but it has much impact: it’s a collection of floorplans of homes drawn by Syrians forced to leave their homes as a result of the war. The chances of them ever returning to their homes as they remember them are slim, and so Foundland asked that they draw the floorplans from memory, and also depict some of the events that took place there.

“We thought this was quite a fascinating thing to do, as most people remember every detail of the house in which they grew up. But then when you can’t return to that house, holding onto this kind of memory is quite special,” says Alexander.

With many of these homes now destroyed, these memories become a validation that they ever existed. This is what Groundplan Drawings aims to preserve.

Right now we find ourselves deep in the age of citizen journalism and its obvious offshoot, fake news. With conflict in the Middle East never ceasing, and versions reported by news outlets not always getting the story right, the everyday woman and her mobile would be the way to tell the world the ‘real’ stories.

But Alexander and Elsrakbi wondered to what extent the authenticity of people's personal stories and pictures could be trusted. Could technology be a tool with which to distort versions of memories? It’s a new-age problem that we’re only really on the cusp of critically investigating as a society. Real-time History is intended to start that discussion.

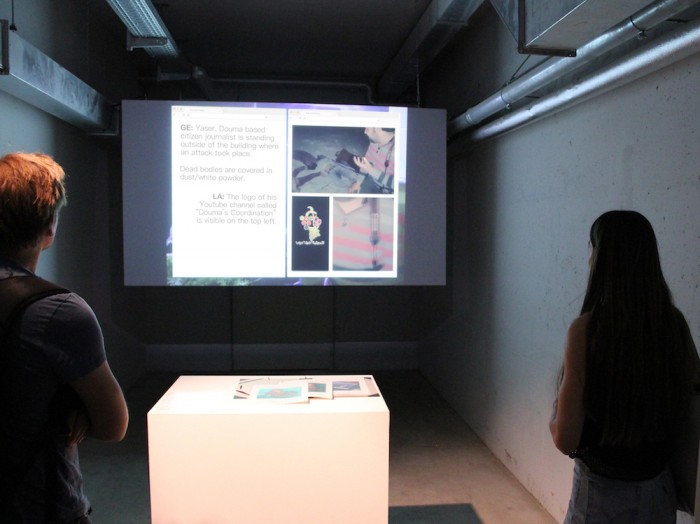

Using the alleged Russian chemical attacks of 2017 and 2018 as a case study, Foundland started to collect evidence in the form of video materials from both sides of the conflict and proceeded to analyse these to investigate the ways the same materials are used in different contexts and for various intended outcomes.

Alexander says that their angle was not to establish what happened, what didn’t happen, what was true and what wasn't true, but more how fiction was constructed in those videos - for example, how the same video was used in multiple places to tell different stories.

With access to the Syrian Archives, Elsrakbi and Alexander painstakingly manually analysed the footage - a process that could only be achieved by using qualitative data - to present their findings in a graphic novel using different windows to depict the different narratives.

Their main aim is not to investigate the truth, but to take a close look at how and why narratives around migration and refugees are created, and to scrutinise how evidence can be used, and abused, according to Alexander. This most recent project also points to ways that the challenges facing migrants are constantly changing and demonstrates how technology is at once a benefit and a hindrance.

Read more:

Two artists use video and sculpture to explore perceptions of history and memory

Alexa Pollmann: Design, migration and a future form of statehood