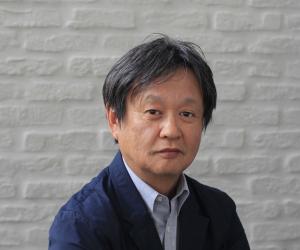

In this presentation at Design Indaba Conference 2014, industrial designer Naoto Fukusawa fleshes out his approach to product design, preferring to see it as a version of “interaction design” with objects as the interfaces.

The Japanese designer, described by Bloomberg Business Week as one of the world’s most influential designers, is most popularly known for his minimalist designs for “no-brand” Japanese brand Muji. He has designed mobile phones and CD players, household electrical appliances and architectural products, furniture, lighting and even fashion.

His approach has always emphasised the importance of an object or design integrating well with its surroundings. But it’s a shift that he observes in the design world as a whole, he says here, which is becoming more and more interconnected. So much so that the university at which he has taught since 1997, TAMA Art University, recently established a department of integrated design.

In fleshing out his design philosophy, Fukusawa lays out his building blocks:

Environment

The “world” in which designers insert their work is “a place where we belong rather than an aggregation of different nations,” he says. It is the stuff that surrounds our bodies.

Aesthetics

Fukasawa defines aesthetics as “the beauty of relations” – it is rooted in the relation of one thing to another and one thing to its context. “There is no singular form that is beautiful anywhere. Every situation and environment allows us to define the beauty of objects,” he says. “The reason why everyone can sense something is beautiful is because people recognise common experiences, behaviours, situations and environments.”

Form

The form or composition of an object is “a boundary line that traces relationships between things and people”. We know it through touch: “People recognise good design through tactile experiences,” he says. But it’s not only our hands and bodies that are stimulated – “our eyes are also touching things”.

Medium and matter

Fukusawa’s aim as a designer is to define an object in relation to its environment. “My role is to draw some outlines in the air,” he says. “Design is like drawing a new outline in space.”

He divides the world or environment into the categories of matter (object) and medium (such as air or water).

We could think of designing as an act of drawing a new outline in the space or an act of arranging matter in order to establish beauty or functions.

As technology has progressed, Fukusawa observes that “matter” has begun to integrate more seamlessly into the human body on the one side (through things such as wearable technology and portable devices) and our built environment on the other (for example, air conditioners, TVs, music listening devices built into walls and buildings).

This doesn’t mean that objects will disappear, however. “We are still left with the traditional objects that we use every day – like chairs, umbrellas, plates, bags…” But these things need to consider the “medium” in between: “From now on the designer’s role is not only to create things but to create interaction or relationships between things, the environment and people.”

Designs need to communicate

Picturing design as a piece in a much larger puzzle, Fukusawa says, “You can’t focus on just one element. You need to consider the whole environment that we share with each other.”

His mental model for a successful design involves starting with the environment and creating a solution tailored to suit it. “You can’t start with the design and make it fit. You must start with the environment,” he says.

Affordance

The designer invokes U.S. psychologist James J. Gibson’s concept of “affordance”, defined as the “random values each environment and situation presents us”, in his definition of what good design should be.

“It’s the way we naturally and inevitably interact with our environment,” he says, pointing to his design for an umbrella stand that draws on the way we naturally lean an umbrella against the wall. It dispenses with the cylindrical holder and consists of just a groove in the floor to stabilise the leaning umbrella.

British artist Richard Wentworth found numerous examples of affordance in a photo series of everyday improvisations people have made to improve their environment. “It’s about doing something without thinking, solutions in harmony with the environment,” he notes. “You can see the human here,” he says, pointing to photographs of bottle tops turned into tiny ashtrays, ramps from street to pavement made with a brick and piece of wood, and a rubber boot wedged under an open door as a doorstep.

If you ask your body, your body is more honest than your mind, he states. That’s why we focus on your body when we make a design.

Fukusawa’s iconic design of a minimal wall-mounted CD player for Muji in 1999 resembles a discreet ventilation fan. It’s a prime example of “design dissolving behaviour”, he says.

Designs such as these draw on our “active memory” – what you remember or are aware of without thinking. They speak to intuitive behaviours ingrained in the human mind.

“It’s the things you do naturally, inevitably, every day. You have to observe how people move, what they touch, how they feel, what they look at around you.”

His Juicepeel juice carton designs from 2009, whose packaging reproduces the look and feel of the fruit, is a case in point. The banana packaging worked on an intuitive level – it had the same weight, texture and temperature of the fruit itself. Realistic details such as brown marks contributed to the effect. But other fruits didn’t work so well – the packaging for soy milk resembling a block of tofu lacked character, and the kiwi and strawberry ones weren’t enticing.

Sometimes it’s the small things that give a design its intuitive appeal, from the rubber base on a bag that has “been borrowed” from tennis shoes, to an indentation on the cover of a notebook mimicking a coffee ring.

“You can tacitly predict the future because all human bodies react the same way if the environment is the same,” says Fukusawa.

Other examples of his work that illustrate his intuitive approach are Muji’s paper shredder, which is essentially a lid with a motor attachment that can be fitted onto existing rubbish bins, and his Grande Papilio chair for B&B Italia, whose curvaceous shape is complemented by a seam up the back resembling a zipper.

“Shape shouldn’t be complicated,” he notes, showing the streamlined taps and sanitaryware he designed for Boffi.

Humans are at the centre – that’s why objects shouldn’t stand out too much.

Designs such as his task light for Artemide, consisting of just two round disks, keep things very simple. “I focus on your mind, not just the things I want to make. It is not about me ... I would much prefer to read your mind or your body as an animal and how it behaves.”

People tell him all the time his products look like they have seen them before. He prefers to see it another way. “My product is already in your mind but you have not seen it yet.”