First Published in

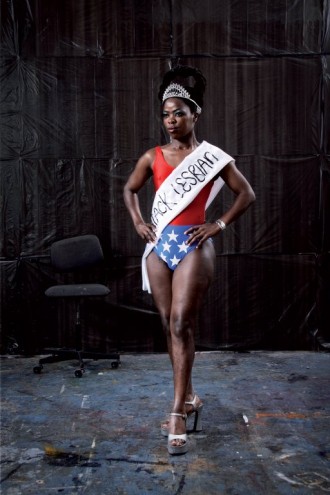

Being a lesbian is not easy for black women. It’s a lifestyle that often has violent discrimination and the threat of “corrective rape” by men in their communities as repercussions. And if they’re lucky to escape that, they still can’t hide from the prejudiced stereotypes of female homosexuality being unnatural or, worse, un-African.

In 2009 Zanele Muholi was awarded the Fanny Ann Eddy Accolade for her outstanding contribution to the study of sexuality in Africa. Fanny Ann Eddy was a gay and lesbian rights activist who campaigned throughout Sierra Leone and Africa. She was brutally gang-raped, stabbed and murdered in 2004. Muholi receiving this award is strangely uncanny in light of the headlines that followed just shortly after that, this year.

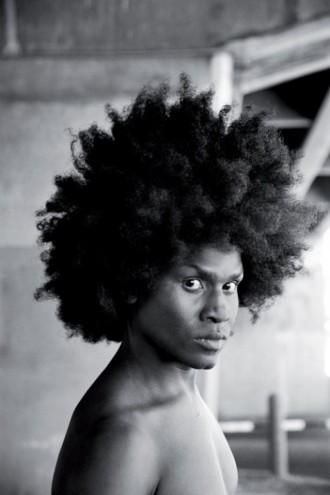

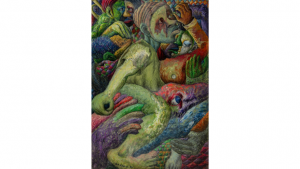

Muholi made headlines when it was reported that the Minister of Arts and Culture, Lulu Xingwana, walked out of the Innovative Women exhibition. Along with work by 10 other female artists, the exhibition featured photographs by Muholi of naked black lesbians in various intimate positions. The ministry in question had donated some R300 000 to this exhibition, which the Minister found to be “immoral” and “against nation-building”. This incident raises questions about the construction of black female sexuality and our understanding and acceptance thereof. Muholi’s work challenges viewers to reevaluate perceptions of black women’s bodies.

Muholi, now based in Johannesburg, was born in Umlazi, Durban. In 2004 she completed an Advanced Photography course at the Market Photo Workshop in Newtown. In that same year she held her first solo exhibition. Muholi has taken part in numerous group exhibitions and has contributed to a number of publications. In 2006 she became the first BHP Billliton/Wits University Visual Arts Fellow. In 2009 she was the Ida Ely Rubin Artist-in-Residence at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

You’ve mentioned that your mother often inspires your work. What sort of influence did she have on your life?

My mother passed away in September 2009 and I really regret not making her more of a priority in my photography. I realised too late that I needed to prioritise my family in my work. I put so much energy into my work and building relationships with the people I work with, that I neglected my own family. My mother raised me and my sisters as a single parent, which is a remarkable feat on the salary of a domestic worker. I cannot begin to imagine how a woman can do that.

The influence that she has had on me has led me to believe that I can do anything with nothing. Her lesson was that you don’t have to wait for money to say something or do something. If you want to tell your story, you have to make do with what you have. My mother loved telling stories; she had a lot of patience and relationships were the most important thing in her life. Even her employer’s children were like her own, even though this must have divided her emotions sometimes. My mother taught me about connections and influences, this has been the basis that has shaped my work. My mother also taught me about having respect for people. It’s the whole idea of “I am because we are”.

In my work I create relationships with people. That is what you need to do if you want to grasp their issues and confront them. My work is about confronting issues. Photographs are about relationships. My participants are like my employers, without them I don’t have a name. They are the ones that help to make sense of my work, they are the ones that create the stories. People who have never been recognised before, or that have been marginalised in some way, matter in my work. Ordinary people also have stories to tell.

You’re a visual activist. Is that a coincidental result of your work or was it a conscious decision for you to try and influence opinions and inspire change through your work?

Visual art is the way in which I try and speak about social and political issues. There is the reality of daily issues that need to be tackled in some way. I have to present a photograph in order for some people to understand this. We need to respect that all people are different, we need to respect their history and understand that they need to be given a platform to express themselves in a way that they are comfortable with. I want to give people a space in which they can be who they are and be ok with it. In this space people are not degraded because of how they define themselves. Visual activism is a form of expression.

Visual art and activism is a universal language. It crosses the language barrier making it accessible. It allows for the individual’s interpretation and for one to create their own meaning in a way that they are comfortable with and in a space where they are not judged.

Visual art is there to share histories, to inform, to educate and to entertain. It is a means by which to ensure that under-representation is erased. In a particular instance it is an opportunity for black lesbians to be brought to the fore. It has the power to serve as a reference document for future generations, to facilitate an understanding.

Your work is about creating a collective history and about telling the story, rather then being the subject or the object. If one thing can be taken from your story, what would you like it to be?

We all have different backgrounds and stories to tell. I want all people to know, but especially those that exist on the fringes of society, that it’s not a crime to “be”. There should be no need to hide your sexuality, as it is intimately linked to your individuality. If you can’t express that, how can you express who you are? I want to give people the confidence to experience that beauty and to present themselves to others, just as they are. If you can’t tell yourself that you’re beautiful, who can?

What do you think it is about your work that resonates with a global audience?

Blackness. The confrontation with blackness. Very few black people have been documented in the way that I document them. It’s like an insider’s view into certain communities. Speaking to and photographing black lesbians is giving access to that community. I speak on behalf of women who are oppressed, I challenge perceptions and allow women to come out on many different levels. History has completely erased the experiences of black women but my work brings another dimension to black women, that of lesbian. It is about understanding that women exist in different spaces and allowing them to just be in those spaces. Even just the idea of a black lesbian disorganises the whole patriarchal setup that is still prevalent in many communities around the world.

Sexual violence against women and children are two of the biggest threats to our social and moral wellbeing in South Africa. What role does art have to play in this fight?

Firstly all people need to be educated about issues relating to gender and sexuality. That is the only way that these things will then be understood without prejudice. Women and children need to be exposed to art as a means of articulation. Art can be used to convey messages in countless ways. Children need to express their sexuality through art, as art is a neutral way to deal with these issues. Teachers can use all kinds of found objects in the classroom to teach children about sex. They can make the sexual body parts out of old plastic bottles, for example, and then talk about its function and purpose, and what should and shouldn’t be allowed. Art makes the message more tangible, ensuring a bigger impact and more relevance.

The recent incident where the Minister of Arts and Culture, Lulu Xingwana, walked out of one of your exhibitions because she believed the photographs of naked lesbians to be “immoral” and “against nation-building”, sparked a lot of controversy. What is your take on this incident?

The fact that Minister Xingwana does not understand that we exist as black lesbians, and that we are contributing members to a democratic society and to our African cultures, is unfortunate. The fact that she does not want to engage publicly on the issues we continue to struggle with in this country like hate crimes, sexual assault, HIV/Aids, poverty and unemployment is simply irresponsible as a representative of a democratic government and against the spirit of our Constitution. The Minister wants to censor my attempt to raise awareness about the complexities we lesbians experience in the new South Africa. This is very un-democratic of her. I may not like how homophobic Minister Xingwana is, but in a truly democratic society the problem is not her homophobic opinion. It’s the fact that she used her power as a government official to try and silence the views and experiences of other women.

A collection of Muholi’s new work, Indawo Yami, is on show at the Michael Stevenson Gallery in Woodstock, Cape Town, until 29 May 2010. Indawo Yami, which means “my place” or “my space”, explores the implications of being black and queer. Website: www.michaelstevenson.com.