First Published in

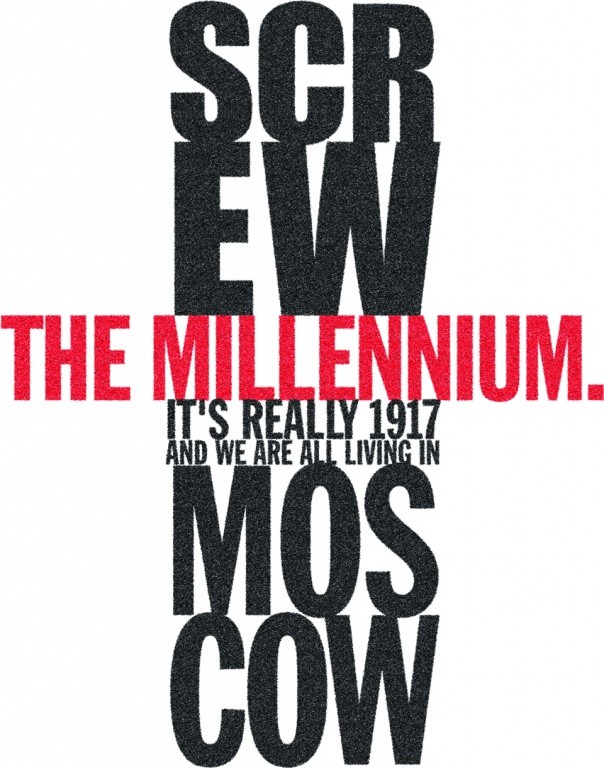

The people’s uprising in Russia gave rise to the most influential movement in modern graphic design. Russian Constructivism still influences communication almost ninety years later. In 1994, South Africa was only the second nation in history to create an opportunity to rewrite its own cultural language. A new social order. A new visual order.

Seven years on, little if anything, has changed. Why?

We all have to come from somewhere. But it's what you do when you're there, and where you end up, that counts. I am a white boy from the suburbs. You see, I am supposed to be a Yorkshire man. I have red hair, freckles and white skin that burns by the moon - let alone the sun. My family (on both sides) are English going back at least 400 years (and probably 400 before that). Both my mother and father ended up here separately, and quite unintentionally, a long time ago. My parents agreed that Africa was a much more interesting place than "home" so, in celebration, I duly arrived in Pretoria 44 years ago, the first of my kin to be born on foreign soil. Ja, ja, we've heard all of this before, from every colour, every culture and every background.

So what does this have to do with graphic design?

Quite a lot, actually. If you live in the USA, you think American and you are American no matter where you started out. The fact that I am here is what makes me African. I see myself as an African. Africa is in my blood, in my head and in my seed. I was born here, I live here, my parents died here and I too will die here. My delicate Northern roots were torn apart by an ancient life force - the same creative energy that started man on his journey from savannah to skyscraper, not far from where we now all sit. Fire was discovered on our land, man’s earliest tales line the walls of our caves and death still stalks our grasslands. A little more interesting than snow, fur coats and warm beer don't

you think?

Africa is a land of contrasts. We Africans embrace excess. Life, death, wealth, poverty, fame and obscurity are all taken to extremes. The world envies our ability to stand on the edge, stare into the abyss then pull back. Why then, given the raw forces that have created us, is design not better able to develop a new language reflective of our history, our past and our future? To be the global creative leaders we should be, would like to be, MUST be. The Nelson Mandela of global design. Are we really the "Rainbow Nation", a "fruit salad", the "unity through diversity" that everyone wants us to be?

Yes. And no. That contrast again.

Yes, because we Africans are closer to our core, our primal origins. We still worship and respect the spiritsof our ancestors through song, dance and ritual.We have something new to offer the world in music, art, movement and craft. Our past is the gateway to our future.

No, because many of us are looking back and not forward. We see only the sins of the past and not the hope of the future. Our design language isrooted in the ownership of cultural lineage - and the dogma of international design annuals.

As a wit oke, I make no claim to own the culture of ballet, opera, space shuttles or abstract expressionism. I enjoy them and I am influenced by them but I am not enslaved by them. They are a part of my past and perhaps my future. But the greater part of both my past, present and future, is the cultural gemors that surrounds us all. The culture of theworsroll, Bafana Bafana, taxis that aren't yellow or black, Castle Lager, bakkies and Egoli. This is the stuff that makes me feel I have a future here. They say to me I'm not in London, Tokyo or New York. I don't want to be Sven in Sweden. I want to be right here, right now, speaking with my own voice, in my own language to my fellow citizens. The important thing (for me, anyway) is to create stuff we all recognise as ours. I happen to like black Father Christmases, BMW convertibles with leopard skin upholstery, pavement hair salons named "all is for God" and ZamBuk.

Amazing things happen when you cross cultures. I have learned about Zulu burial customs by walking the battlefields of Isandlwana. About eating cooked sheep eyes from Seaman Chetty in Durban's Victoria Market. The taste of ijuba in a crowded men's hostel and on the six-day bus journey from the DRC to the streets of Hillbrow. We have all around us the very stuff of our creative fantasies. Creative freedom. An opportunity to create something new and wonderful. Something not seen before. Something that can be exported to every corner of the globe. There is no roadmap, no "what's right" or "what's wrong". Nothing exists. We have a chance to create it all. To have the famous of London and New York copying us - using our language to unite their own cosmopolitan cultures.

So why is little of this happening? (Come on, you know it's true). Maar daar's a vlieg in die salf...

Are we ashamed of our roots, our traditions and our symbols? There are amongst us creatives, academics and "big business" folk who see Africa, it's visual language and it’s culture as being "Third World" - and all that that label stands for. “We are an ‘emerging economy’, so we must strive to look international.” Less African - more global. Every day I am asked to design a brand identity to “look like it's not African - or at least make the African part look nice”. There are fellow creatives, here and abroad, who accuse us of exploiting "African culture" by using traditional indigenous craft patterns and symbols - as ingredients in a new and common visual conversation. Well, tough shit. I happen to see indigenous African culture as an equal part of my own culture. I have huge respect and love of our collective and shared heritage. I am surrounded by it. I have absorbed it. I have embraced it.

As yet, there are no "rules" as to what's right or wrong - so we must accept that trying is more important than succeeding. Many of us have long moved on from the beaded borders and the Ndebele mural to something more layered, more subtle and more personal. Creativity thrives on adversity. We live in one of the most violence-scarred societies on earth. The prospect of a gun to the head certainly sharpens the creative pencil. It's a huge advantage in the design process and a chance for every one of us to speak with his/her own voice and be heard. It's an ideal opportunity to explore new ways of communicating. Let's escape the 'there are no black designers' syndrome and bring together creative spirits from music, dance, fine art, craft and every design discipline before it’s too late. Before we are consumed by global brands and mashed into a collective American TV soap opera. Let’s do something about real issues that effect us all. And prove design can "feed people".

So what do we have to do?

We have to collectively believe that South African design is going to make a difference. We have to become organised with a common goal (THINK). We must escape the tyranny of local advertising views on design - those ad wankers who do crap work and refer to designers as “the guys who do logos”. They are invading our turf (in some cases even doing a better job). We have to lose this obsession with being "big in NY or London". One look at D&AD should convince any local ego that it ain't gonna happen. Instead, we should be trying to be big in NY or London with what they don't have. The very special creative spirit of Africa. We have to escape the safety of Sandton for the streets of Hillbrow. To become real people doing real design.

Connect. Explore. Experience. Create.

We have a chance to rewrite our visual history. Our way. Design's way. Maybe even your way.

What are you doing?

Taken in the MSINGA area (southern Zululand). I was accompanied by a Zulu historian and linguist who was able to obtain permission to photograph from the families of the deceased. In most cases, the graves were within the parameters of the family kraal (in the case of men). What interested me was the transition from traditional Zulu graves (rock and thorn tree enclosures) to a more western and modern looking grave. The interpretation of the headstone is a particular point of interest. The names of the deceased are self-explanatory.