Every year after harvesting, when the people of Matobo in southern Zimbabwe have more time on their hands, the women paint the exterior of their huts with intricate designs using charcoal, ash, water and soil. When the rains come in summer, the murals gradually wash away until – come the onset of winter – the women start again.

It’s an annual ritual that replenishes the women’s cultural traditions as season after season they beautify their homesteads with continually changing imagery.

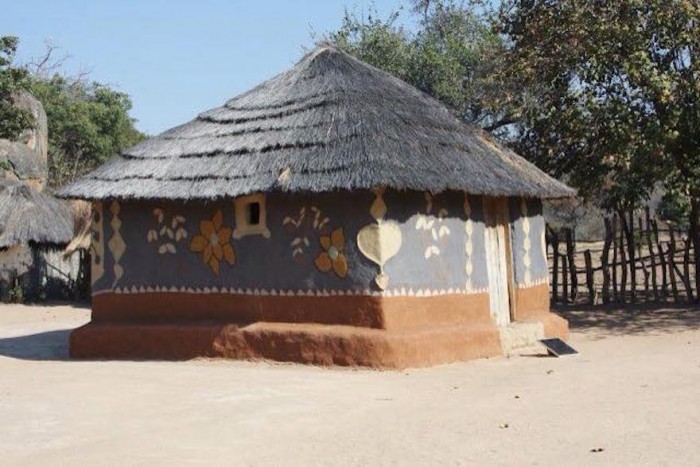

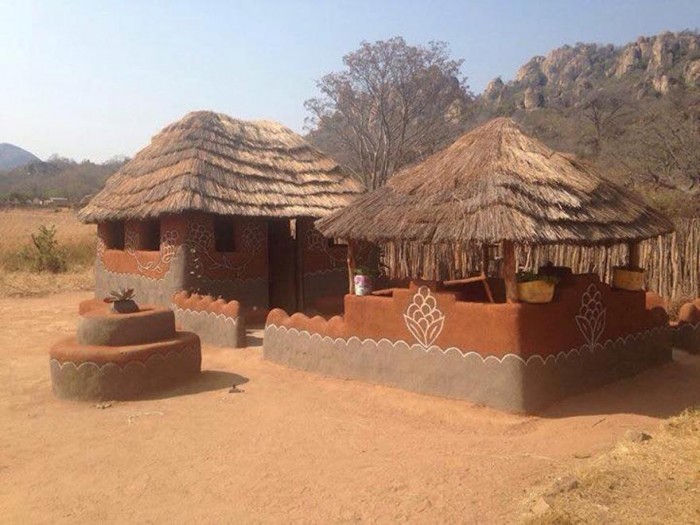

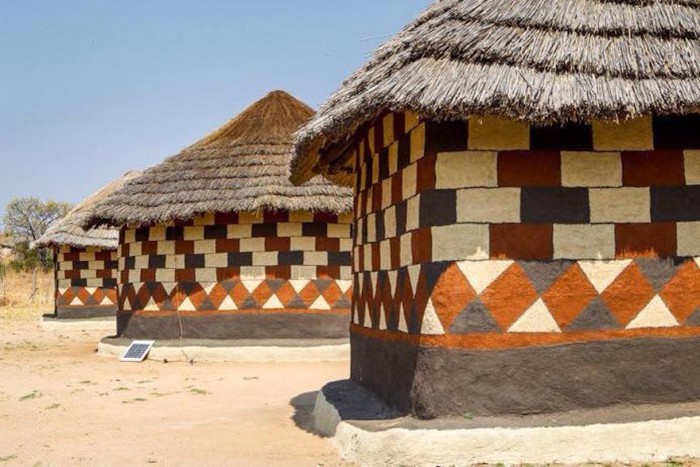

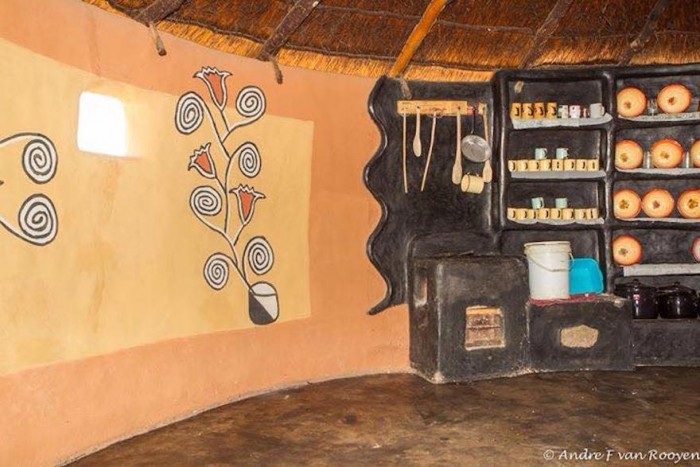

The women translate the rhythms of their lives into abstract patterns – zigzags and diamond shapes, scallops and stepped lines – as well as motifs taken from nature. Giant flowers burst out from a terracotta background, tendrils unfurl and elephants and buck parade across the walls.

But the traditional art form is in danger of disappearing as more and more Zimbabweans opt for brick houses rather than mud huts.

“Architectural traditions are changing in design, style and type of construction materials,” says Pathisa Nyathi, a prominent cultural historian. “Painting by brush has eroded the artistic tradition that has for centuries been executed through the use of hands.”

Nyathi runs the Amagugu International Heritage Centre in Matobo, which works to preserve indigenous Zimbabwean cultural traditions and knowledge. He and a group of like-minded volunteers launched an incentive to encourage the local women to explore their creativity when adorning their huts. The My Beautiful Home competition started off small in September 2014 in just two wards of the district.

Nyathi and his fellow competition organisers – John Knight from the National University of Science and Technology, photographer Andre van Rooyen, Cliford Zulu from the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo, Veronique Attala from local car-wash business Squeaky Clean, writer Violette KeeTui and Butho Nyathi from Amagugu – opened the competition initially to those whose houses already had been painted.

The restriction was intentional so that the committee could track the impact of their initiative in subsequent years. In 2014, 30 homes were entered and seven received prizes. This year, the competition was open to seven wards with close to 300 women entering and 77 receiving awards.

The judges travelled around the district for two months, visiting homesteads and choosing 10 finalists in each ward.

“Throughout, we met strong, independent women, often running single parent households and on the flip side, men who were evidently proud and supportive of their wives and their work and often, when news travelled that our car had been spotted in the area, waited on the side of the road and waved us down, urging us to come and look at their wives’ handiwork,” says KeeTui. “If nothing else, this competition, we realised, has given women stature, and recognised and rewarded their role in the homestead and beyond.”

They were so impressed with the creativity they saw that they added new award categories to include the best exterior, interior and overall homestead as well as a special prize for innovation and two Photographer’s Choice awards to encourage artistry among the participants.

Thulisa Ndlovu’s striking designs in black, brown and white stretching from earth to thatched roof took the Gold Indlu, or Best Exterior, award. Ironically, the pattern is modelled on brickwork in alternating colours, with a chevron band below.

“The same consistent design covered each hut and there was a clear understanding of space and form, not only in the design but in the placement of the huts within the compound,” said the judges.

Second place went to Queen Ncube whose vibrant floral paintings broke away from the earthy monotones usually used in the area. Her depiction of the flowers’ petals also showed a sophisticated understanding of perspective and three-dimensional form, even though it was rendered in flat shapes.

To be considered for the coveted Gold Ekhaya award for best overall homestead, all the structures in the compound had to show a consistent level of thought and creativity. Winner Doreen Nyathi developed her own delicately rendered floral design that she applied to all the buildings making up her home.

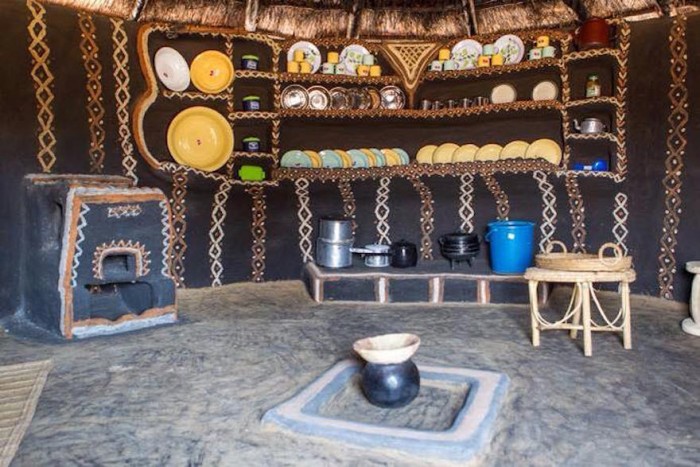

What really stood out for the judges, however, was the ingenuity the women showed in decorating the interiors of their homes. With so little at their disposal, the women showed an inspiring degree of inventiveness in building shelving units and even furniture such as chairs into the hut’s structure. “Great efforts had been taken not only in creating an indoor space that was practical and efficient, but also aesthetically pleasing,” said the judges.

Winner of the Gold Iziko award for best interior went to Sithembiso Sibanda, whose interior stood out for its unusual black background against which the stylised black and brown designs popped out. Second place went to Sichelelise Mkandla for her massive kitchen with bold black and red fittings and third prize went to Sichelesile Ngwenya, last year’s winner of the Gold for the Best Interior. To the clay oven that wowed the judges last year, Ngwenya added an innovative sink with an outlet pipe that waters a small vegetable garden outside.

The impact of the competition can clearly be seen in the transformation of the same huts over the one-year period. Take Thokozile Dube’s kitchen, for instance: in 2014 when the My Beautiful Home competition was introduced, her hut was painted with a black shield-like motif and a middle band of red ochre. In 2015, she used a more elaborate geometric pattern and finished the low wall around her entrance with sculpted elements.

The competition committee hopes to take the competition throughout the country and while they acknowledge the massive effort it took, they are heartened by the increased support they got from sponsors providing prizes for the women.

As they generate more pride among the Matobo communities, Nyathi and his compatriots are also documenting their findings and conducting research so that the symbolism of the painted imagery is not lost. They are also hoping that the painted huts will turn what has been a passing tourist attraction into a major drawcard that creates some income for the residents.

“There is a danger that if this trend continues Zimbabwe will be left with little to distinguish it from any other part of the world as poorly adapted versions of bungalows replace the culturally rich, climatically sustainable and economically viable homesteads to which these decorations are applied,” says Cliford Zulu, a curator at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo.

If the competition continues to elicit as much interest in the future as it has in only one year, it’s not far-fetched to imagine it having a reverse influence on its Western-style counterparts in the cities.