First Published in

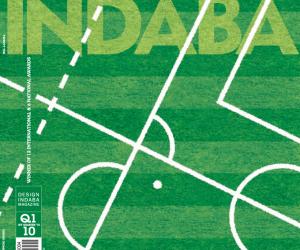

All stories start long before the first word. This is a small story, on a big stage, about one man and how the details of his life helped him play a small but immensely big role. The story is set here, in South Africa, the country that Wikipedia – for once surprisingly accurately – describes as a country “marked by immigration”, a country that will soon welcome the world when it hosts the first FIFA World Cup on the African continent.

The man in our story starts as a boy, the child of Portuguese parents, the son of an immigrant, the charge of a Zulu nanny. He grows to be a man with an incredible talent in design. Talent that comes in equal thirds: passion, insight and dedication. Talent that will lead him to create the logo that precedes and then supports the first officiated moment of the 2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa.

Like religions FIFA, the Vatican of the sport, has a very set idea of what symbols should and will be used to communicate to the masses. Stage left, our man is a disciple. A man named Gaby de Abreu, a designer who has won numerous national and international awards, the co-founder, co-owner and group creative director of Switch Design. Once a child who grew up at the bottom of Corlett Drive in Johannesburg, a man who identifies himself with the idea of an immigrant Portuguese community, but is wholly South African in this outlook, and, most importantly, a man who wished to dedicate his life to professional soccer, but instead opted for the responsible choice: design.

As the child of the “typical Portuguese fruit-and-veg family, the ones who lived across the road from the shop”, De Abreu and his brothers and sister were obliged to help out at the shop from an early age. He says that in the Seventies this community had the feeling of a mini Bronx – a place where your neighbours played a huge role in your life, where families supported each other, and kids helped out in the shop and rode bikes in the afternoon, often acting as messengers. “It was like the movies,” he laughs, “but without the Mafia”.

His father came from Madeira with a limited education and spoke very little English. As the eldest of four children, organisational tasks such as balancing ledgers, and checking and writing contracts fell to De Abreu. But while his brothers took an interest in the running of the shop it was graphic design that instinctively captured his heart: “I loved it, I was more interested in doing my dad’s signs outside the shop than ever doing the money side of things.”

At night, after working in the shop for many hours, their father passed on his passionate love of soccer, teaching the children about the European soccer teams while they listened to games on the radio with Portuguese commentary. “In the South Africa of the time, my heroes were Pele and Eusebio. We didn’t see colour, the player was the hero,” says De Abreu.

When he was very young, De Abreu’s mother passed away and, as often happens in South Africa, the family domestic worker, Victoria Tshabalala, became the primary maternal figure in the children’s lives. “Because my father worked the whole day, got to work at 4am, came back at 8 or 9 at night, Victoria was there... She became the mother figure and she started teaching me about her Zulu culture. So I used to play soccer with the black kids in the neighbourhood.

“As a kid I got to know all the black teams. Underneath the bottle tops of Coca-Cola you could find all their faces. I got to understand who all the players were. And Victoria taught me more: In those days the teams were separate, black league and white league.”

All through school, De Abreu played soccer, hoping to become a professional player when he matriculated. At the age of 14, he played at the Orlando Stadium in the curtain-raiser game of the Mainstay Cup Final between Orlando Pirates and Moroka Swallows. The game was one of the first matches in apartheid South Africa that took place between a black and a white youth team.

“We played a Soweto 11. After the game, the stadium was so full that we had to sit around the field next to the players’ benches. It was the late Seventies, the country was burning but it wasn’t that we would get hurt. Nowadays, when you see old footage, there we are – that is the one game that seems to have been televised.”

At school, De Abreu got his colours in soccer but despite his passion and talent, when he matriculated he had to choose between a professional sports career and “doing the responsible thing”. As the eldest he felt that the right thing to do would be to get a degree. He chose to study design at Wits Tech, but continued to play soccer at provincial level, staying in the Southern Transvaal team from the age of 18 through to 32. After Wits he joined KSDP Pentagraph (which has gone through many incarnations and is now known as the Brand Union) where he became creative director after eight years. In 2000 De Abreu co-founded Switch Design, an award-winning company that aims to change consumers’ perceptions of brands using strategic design.

Over the years, De Abreu has personally worked on such iconic South African logos as SAB, the redesign of the Springbok rugby team’s emblem and the Olympic Torch Relay logo. He is also the brand custodian of Orlando Pirates, an honour bestowed on him when he and Irvin Khoza met and bonded over their mutual love of local soccer and the history of the game in this country. He says that the game of soccer has influenced how he works: “Because of my soccer experience I know about teamwork. When you are a creative director there are a lot of ideas that get brainstormed, but it’s the team that has to put them into place.”

“As a designer, you always aspire to do an Olympic type event,” says De Abreu and when the opportunity to pitch for the 2010 World Cup logo came, De Abreu’s experience in design and his natural affinity and passion for soccer combined to form the winning symbol.

In the first stage of the logo pitch 30 companies presented their credentials; then five companies were chosen to submit a few logos each. “At our place the whole company was involved, even the tea lady – and there were some really good ones. But somehow they chose mine, which is some type of serendipity. Soccer has always been part of my life and in a weird way, soccer has come back into my life.”

For the logo, De Abreu wanted to portray what makes African soccer different from the European game. “European football is quite technical – they play with strategy in mind. Whereas here – we don’t score too many goals, because we play with flair. How do you show that happiness, that flair, that is so unique to African football? What I thought of is the bicycle kick – because it’s one of the most difficult things to execute, but African players do it so incredibly well.”

The logo shows a San-styled man executing this kick, with the South African colours and the iconic map of Africa in the background. “From a design point of view, it’s not the most classic logo in the world. Right in the beginning the design community gave me so much flack – and I kept quiet the whole way because they didn’t know the process. They didn’t understand that this logo needed to tell a story. And, as you can imagine,” he adds, “FIFA has very strict guidelines”.

The logo had to encompass a number of things – the brief asked for unity with past logos, it had be South African but with international appeal, it had to be celebratory and welcoming, and most importantly show African-ness. “A logo is supposed to be simple, but with this one I had to ensure that it was not just South Africa but Africa. From Cape to Cairo, it had to work.”

The logo and poster have been put up all over the world, on the arms of De Abreu’s own heroes, outside airports in Portugal, above barbers in Lagos. He smiles. “I know these stories. I sat on this field on the stadium in the horrible days of apartheid, at Orlando Stadium. In my own little way, now I can make a difference.”

Now let the story begin: that first whistle, the thud of the soccer ball and the roar of the world’s crowds nestled around TVs watching the only religion that unites – the polytheistic world of football. “The shaman is now the soccer player, the gods are in the fields, and people are watching them, hero worshipping. My aim is to show Africa united through this – after 2010 that is what will count”, concludes De Abreu.