Part of the Project

In a beautiful big, flat-top Albizia outside ST(E)AK’s house, a tree-feller is busy with a chainsaw. The tree is the stage for a thrilling, edgy, gut wrenching piece of performance art. Dangling from a limb, six meters off the ground, with a chainsaw strapped to his waist, he lops branch after branch from the iconic silhouette. As the tree is reduced to a nub of broken wood, ST(E)AK is unhappy.

Staring up at the nasty aftermath of the chainsaw’s destruction he mourns, “That was such a great tree man, my own private giant bonsai. Now it’s fucked.” Only moments before the extreme pruning session began, ST(E)AK was holding forth about another act of desecration inflicted on the beautiful trees of landscape painter J.H. Pierneef; one hanging in the Johannesburg Regional Court had been damaged by water while another had its frame ripped off and burnt for firewood at the Free State’s Dihlabeng municipality. We were discussing Afrikaans culture, and the ironic difficulty of fully recognizing all the aspects of your own culture, from the inside. “What is Afrikaans culture now anyway? It’s not a fucking braai and a brandy. Maybe its Pierneef?”

Dismissing a clutch of kitschy traditional Afrikaner stereotypes in one breath, ST(E)AK is angry at the desecration of the great painter’s work. Unwilling to associate himself in any way with a form of cultural identity that reeks of political nationalism, he robustly defends Pierneef (as an artist) against the perception of being racist. Though he’s the first to admit his uncertainty over where the boundaries of Afrikaner culture lie today, ST(E)AK does believe a large part of his own culture is what he calls “a personal struggle for survival”.

As an artist, ST(E)AK’s work is literally defined by his struggle to live. Not in the conventional starving-artist-in-a-garret kind of way, but in the drop dead, heart attack kind of way. At the age of 19 Stefan Naude (ST(E)AK’s real name) was diagnosed with Marfan syndrome, which almost cost him his life and resulted in him receiving a pacemaker. Since then he’s been fitted with a succession of four, and there is nothing quite like a bum ticker to make you appreciate what you have here and now.

Making the most of what you have appear to be words ST(E)AK lives by, and while he couldn’t care less about politics, the attribute he admires most in fellow Afrikaners is an ability to adapt. Whether or not the root cause is his cultural heritage or personal medical circumstances, ST(E)AK is nothing if not adaptable. Since his brush with mortality as a teenager, ST(E)AK has moved through life by concentrating only on what is in front of him at any given moment. His apparent ease of movement is purely because he adapts so comfortably to new circumstances. “I never planned any of this,” he says, “I never, ever, wanted to be an artist”.

The transcript of his life so far seems to back him up. Born in 1976, the young Stefan Naude spent the bulk of his childhood in Randpark Ridge, near Johannesburg. At age 15 he fell in with a loose crew of young skaters, “riding waxed curbs, banks and the three steps in front of the Post Office all day. Those were some of the best times of my life.”

Along the way he picked up his nickname, courtesy of an American classmate who teased him by mercilessly playing on the pronunciation of Stefan Naude, calling him “Steak-Farm No-Idea”. The “Steak” bit stuck, the brackets added later as a tribute to Jean- Michel Basquiat.

Getting out of school in 1994, ST(E)AK moved to London. Striking out on his own in a foreign city was a conscious disavowal of any expectations his parents and society had for him. Working at skate shops and later as a pizza chef, to get by and getting to know London from the street up, as a skater, open to anything that came up.

What came up was an invitation to participate in an exhibition called The side effects of Urethane. “It was huge, 10 000 people came to see the exhibition and there were several floors of work – including a massive indoor skate park”, he says. His piece, Economic Leftovers was well received – strangers complemented him on his talent and a few agents even came calling. ST(E)AK didn’t follow up.

Like many creative people ST(E)AK suffers from “a beautiful curse”, which is how he describes his condition of acute bipolar disorder. He admits that it’s at the root of some of the best work he’s done, but it’s also the reason he is always searching for new beginnings, starting over at the bottom. What has saved him time and time again is his concept of Afrikaner adaptability. Leaving one place for another means a new opportunity to engage in his favourite pastime of watching people and waiting to see what lands in front of him.

In the past decade, that nomadic trekboer penchant for finding new artistic territories has drawn ST(E)AK to a variety of different media and opportunities.

In 2001 he was one of the founding members of SESSION skateboarding magazine and worked as an art director on many other youth culture magazines at the time.

In 2007, he embarked on a two year project to document his life with a cell phone camera. He titled the resulting collection of pictures JAPANESERUBBERONCOUNTRYTAR, drawing the attention of a Joburg based ad agency who loved the series so much they sent ST(E)AK out to document live bands for a Jägermeister campaign.

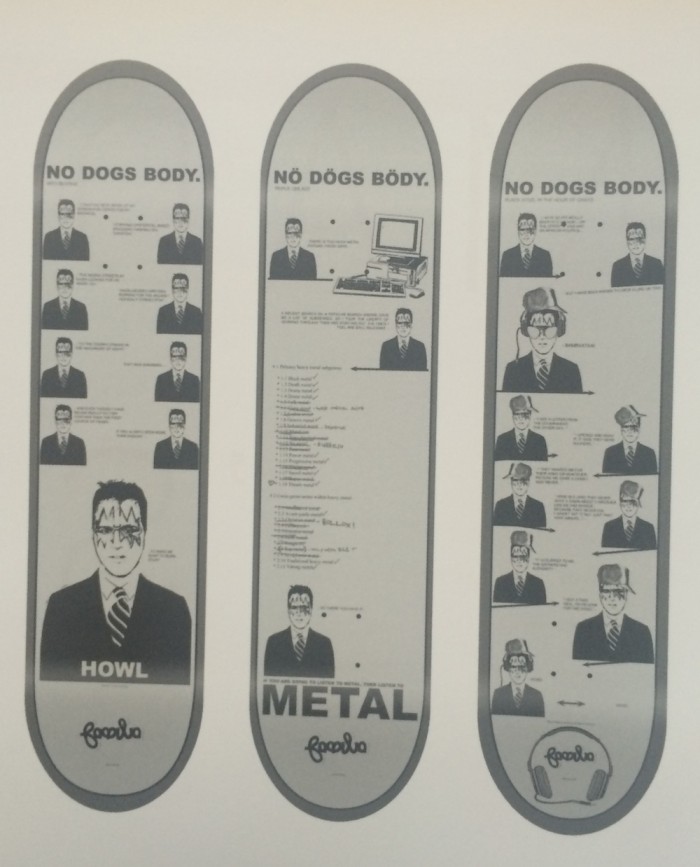

The following year, in 2008, skateboard company, Familia skateboards invited ST(E)AK to design a range of deck graphics.

The result was a series of silhouettes of kitchen utensils and cutlery, printed onto the skateboard decks. Familia were so pleased with the results that he was invited to produce the following year’s range.

ST(E)AK was invited to participate in Them and Us, the 2009 African/European poster project curated by disturbance and Noel Pretorius, creating a conceptual piece inspired by patterns derived from quantum physics and chaos theory.

In 2009, Trent Read of the Everard Read Gallery saw an image of the piece ST(E)AK had produced for the Side effects... show in London. He made contact with ST(E)AK to see what other work he had produced and after reviewing some of his work, Read offered ST(E)AK gallery representation.

2011 saw ST(E)AK creating work for seminal Durban club Unit 11, where he produced a series of posters to advertise events at the club. He set about reproducing versions of Jeff Wall’s photographs Destroyed Room, leading to his haphazard arrangement of chairs wittily named, The effect of Hip Hop on African politics.

Underlying his creative wanderings and the medical conditions that play havoc with both his heart and mind, ST(E)AK has the fortune of creative insights that capture a restless and emerging young Afrikaner struggling to survive in the world. Its not an easy perspective to come to grips with, but well worth the journey.