From the Series

Larry Harvey, founder of Burning Man, famously drew a line in the sand of the Nevada desert and proclaimed, “From here onwards, everything will be different.”

On the other side of that line was a new set of values: a decommodified culture of sharing and gift-giving that burners say has a profound spiritual impact on all who experience it. A number of the speakers at day one of Design Indaba Conference 2015 drew metaphorical lines in the sand – whether in the world of branding or industrial production or digital technology. Though diverse in their disciplines and ways of engaging with industry, there was a chorus of defiant no’s – from Hella Jongerius’ call for new industrial values that pit quality over profit, to Stanley Hainsworth’s “conversion” from the religion of brands to striking out on one's own.

It’s a lesson local communications group Joe Public United learned the hard way, after merging with an international network that ultimately saw them lose their focus on creating a culture of excellence and ideas. In 2009, they bought out their owners, opting instead to run a 100% South African-owned agency. They recommitted to the “mighty why” of what they do: growth.

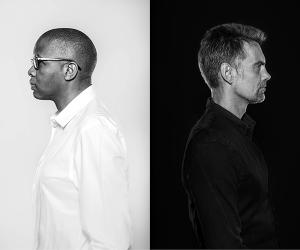

“If you’re uncomfortable, it’s a good thing. It means you are growing,” said Joe Public's Xolisa Dyeshana.

Every project is seen as an opportunity for growth and service: “Ultimately we serve the growth of our country,” said colleague Pepe Marais, through projects such as One School at a Time, which works to improve underprivileged learners’ performance in subjects such as maths by focussing their attention on upgrading their fluency in English.

Jongerius rattled the cage of industry, proclaiming, “There is too much shit design” to rapturous applause from the audience. “I’m fighting for new industrial values,” she said, laying out her mindset as a “pastor” – not a “trader” – of design. She called for a holistic approach to design that considers quality above all, but one that tolerates imperfections. “Perfection kills everything,” she concluded.

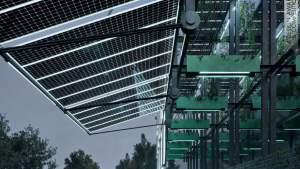

Naeem Biviji, who runs his architecture practice Studio Propolis with a rare devotion to handcraft, concurred. Being off the radar of the mass design industry – he is based in Nairobi – plays a huge part in his orientation. "Lack of resources, tools and craftsmanship forced us to innovate. But we turned this into an opportunity,” he said. He and his wife, Bethan Rayner, make everything themselves by hand in the workshop alongside their studio.

“Our hands-on way of making everything ourselves positions us somewhere between the trade and profession,” Biviji said, meaning at times they have to work closely with manufacturers to get their designs right; at others they have to learn to let go for the sake of the end result.

He dubbed this approach a kind of “design tolerance” that tries to take a gentler approach to collaboration.

There were lots of other examples of designers going it alone: The Workers setting up their own studio after graduating. And, rather than choosing a design specialty, opting to “go up” to operate at a level that connects digital technology, interaction design, product design and branding; recent graduate Ackeem Ngwenya, who has devoted himself full-time since graduating from RCA and Imperial College London to his Roadless Wheel designed with rural users in mind; Stanley Hainsworth, who stressed the need for interconnectedness but from a position of creative freedom in his self-initiated studio, Tether.

Michael Bierut’s new book, How to: Use graphic design to sell things, explain things, make things look better, and (every once in a while) change the world, which he spoke about for the very first time at Design Indaba, is a manual of design’s many uses as seen through the lens of this acclaimed Pentagram designer’s career. Underpinning the lessons he shares and example of projects completed is a generosity of spirit that reveals both hiccups and successes.

It is ultimately the work he did for NYC public school libraries that brings him back to why he does what he does. A smallish job in terms of pure graphic design, it nonetheless encompassed the creation of artwork by different illustrators for use in a frieze-like installation along the libraries’ walls. One of the librarians related to him that her last sight everyday when closing the library and switching off the light that shone on the mural, was to see the children’s happy faces. Her knowing why she was doing what she did for a living ultimately reinforced what he was doing as a graphic designer looking to have some impact on the world.