As the impassioned debate which characterised the awards proved, it is far simpler to define what African architecture is not rather than what it is. It is not, for example, a stereotypical ‘tropical architecture’ or buildings adorned with a light sprinkling of tribal motifs. African architecture is not a European or American architecture cut and pasted into African contexts. And neither is African architecture an exercise in object-making and generating icons. Anna Abengowe, a member of the judging panel and Nigerian architect based in New York, explains that the awards’ judging process "elevated process and complexity over form, we were not looking for 'sexy' form", and instead emphasised the importance of debate and participation in African architectural production. Perhaps, fellow judge and South African architect Tanzeen Razak proposes, African architecture is an architecture which offers voices to those historically without, integrating and making visible narratives which have previously been subverted and silenced throughout Africa’s violent and tumultuous history.

The uMkhumbane Museum by Choromanski Architects – the grand winner of the Africa Architecture Awards announced at the ceremony held at Thomas Heatherwick’s newly opened Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town – does exactly this, providing a mouthpiece for those forcibly displaced from their homes during apartheid in the 1960s. The publicly funded museum is in the township of Cato Manor near Durban, one of the largest ‘forced removal’ sites in South Africa, and preserves the culture and globally significant history of the local people. "The winning project showed the importance of process and the social contract", Abengowe explains. "It shifted the frame from the final product and object-making." Perhaps this fact alone was enough to excuse the generous smattering of ‘Zulu emblems’ which garnish the drum-like facade.

Over 300 submissions from 32 African countries were entered into the Africa Architecture Awards’ four categories – Built and Speculative projects, Emerging Voices and Critical Discourse. The winning projects were not easily agreed by the jury who spent two strenuous days agonising over their final decisions. "Consensus was not always met", Abengowe concedes, "but we didn’t feel it was a necessity." The hotly contested shortlist was decided by a refreshingly gender-balanced judging panel which, alongside Olweny, Abengowe and Razak included South African architect Phill Mashabane and urbanist Edgar Pieterse, Guillaume Koffi, the co-founder of Ivory Coast practice Koffi & Diabaté, and Patti Anahory, an architect from Cape Verde.

The merits of the different projects were not the only source of disagreement among the jury members. While steering panel member Mphethi Morojele argues that "the world is Africa", the indiscriminate inclusion of architects practising outside the continent in all categories was openly disputed, and the inclusion of a separate category for international architects, often living and working in very different conditions to those on the African continent, was proposed for the next awards cycle as a result.

An international winner of the Africa Architecture Awards arguably would have conflicted with the awards’ ambition to set an ‘alternative precedent’ for architects in Africa. This controversy may or may not have contributed to the contested overlooking of Toshiko Mori’s swooping cultural centre in Senegal, which was awarded a Certificate of Merit but was beaten to first place by the uMkhumbane Museum designed by South African architects based in Durban. Hopefully, this dispute was not also responsible for the notable omission of other commendable submitted projects from architects including BC-AS (based between Brussels and Addis Ababa) and the late Australian architect Ross Langdon (with designs implemented by Studio FH), both featured in AR May 2017.

"Colonialism is the elephant in the room", Razak acknowledges, describing the tensions and contradictions in designing "First World architecture in a Third World landscape". And yet inescapable overtones of modern-day colonialism threaten to undermine the awards themselves. French multinational construction company Saint-Gobain is the founder and sole sponsor of the awards and has been very honest about the ambition to grow their business on the continent through the awards programme. To their credit, however, they ensured that the awards were entirely free to enter and the programme has been subject to rigorous scrutiny and robust discussion, by both steering panel and jury, aired publicly at a free colloquium following the awards ceremony at the University of Cape Town.

Also openly debated was the omission of judges’ visits to shortlisted built projects – the shortlisting was based on the entrants’ five-minute films along with drawings and a 500-word overview, while the winners were deduced merely from an additional ‘technical review’. While Abengowe stresses that ‘visiting is imperative’, the innovative film entry format was widely lauded, despite the fear that some projects may have been lost behind an under-developed filmic language.

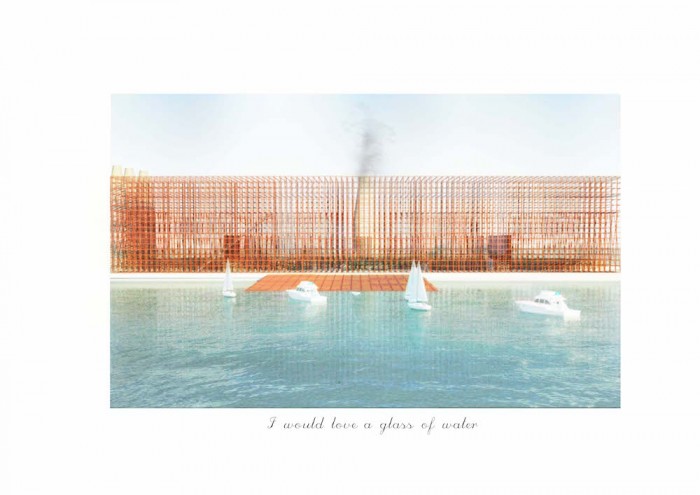

The triumph of the Africa Architecture Awards lies in the incorporation of the Emerging Voices, Critical Voices and Speculative categories, in which the abundance of thought-provoking student work and brave speculative projects bear testimony to a lively culture of critical discourse and architectural discussion on the continent. Student projects were both provocative and creative, perhaps showing up the built projects in their ambition and imagination. Aissata Balde’s arrestingly profound student project, which won the Speculative category, reimagines the journey of migrants and their relationship to different territories, borders and edges, states and nations, through a series of beautiful drawings. "If you’re going to speculate", Razak reflects, "speculate big".

The inclusion of these awards categories, uncommon in many other awards programmes across the world, are indicative of an architectural culture with eyes firmly looking to the future. Abengowe recognises that the profession’s imagination lies in "could-bes and projections", while steering panel member and head of the Graduate School at the University of Johannesburg, Lesley Lokko, likens the awards to Anna Akhmatova’s encounter with Isaiah Berlin in Leningrad in 1945, whom she described as her "guest from the future".

What is undeniable is the invaluable platform the Africa Architecture Awards has offered to the architectural discourse on the continent, making visible the architectural opportunities in Africa as much as the clichéd challenges. "There is strength in disadvantage," evangelises Razak. "You can build a building before you’re 30, and we have been living sustainably and collaboratively for centuries." As Lesley Lokko points out, the discourse of race, gender and power in architecture has had a long gestation period since its first emergence in the 1990s. Closing her characteristically sparkling speech at the awards ceremony, the inside of the faceted jewel-like windows of the Zeitz MOCAA glittering in the background, she makes a final call to arms: "Speak up, speak out, speak back".

This article was written by Eleanor Beaumont for The Architectural Review. From Art Deco apartments to hospitals to wooden skyscrapers, the AR’s May 2017 Africa issue is online now at architectural-review.com and available to purchase here.