From the Series

For someone who works in the tech sector, UX designer Mark Kamau spends a lot of time not only on the road but in some of the most remote parts of Kenya, and for good reason. Kamau is the user experience director of start-up, BRCK and they are on a mission to bring wifi access to more people who cannot afford it.

There are currently about 3 billion people in the world who are offline, the majority of whom are women. Through a range of products, developed in Kenya by Kamau and his team, they plan to change that one Brck at a time.

It started with the SupaBRCK which lets people access the internet during powercuts.

"BRCK is a back-up for the internet in the same way you can have a generator as a back-up for electricity. It uses a sim-card and lasts for up to eight hours and it broadcasts WiFi to about 30 of us," says Kamau as we chat over breakfast in Kigali.

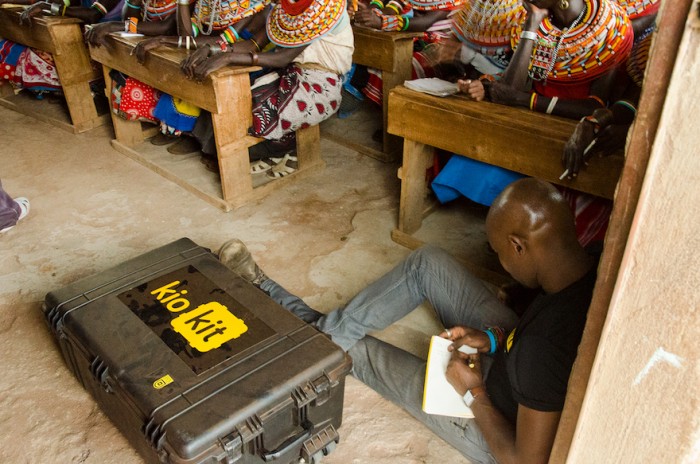

Following the success of BRCK, they realised that it could also be a useful tool for education. This led to the development of the Kio and Kio Kit as a way to bring virtual education to people who live in remote areas that often do not have electricity or other infrastructure that people in the cities take for granted, like a decent Wifi connection.

The Kio Kit turns any classroom into a digital one through the help of a Brck as well as 40 tablets that comes with headphones and designed with young people in mind.

Kamau, who was a speaker at this year's Design Indaba Conference, explains that during the testing phase his job was to go to remote schools and to work with young children, to see how they think and to help redesign the tablets.

"I noticed kids didn’t know where to press the start button because the whole tablet was one colour, so we made the colour [of the start button] orange. Before you’re 8, the way your psyche works is that kids respond to colour quite a bit."

"I started studying the psychology of children and how that affects the way they interact with technology and colour. All of sudden the change of the headphones from green to yellow, and the start button to orange meant that it did not matter where you take the tablets, even if the kids have never seen a tablet before, they will be able to turn it on," he says.

One of the lessons he learned is that because young people instinctively knew what to do with the tablets, the Brck team needed to work with the teachers to help them be more in control of their classrooms.

"Teachers struggle with technology while the children, even in rural areas, pick it up and go. The teachers were starting to lose authority in the class, they felt underminded and they felt threatened, and for them it starts being a negative thing."

"So, it’s my job to design a process that allows them to be in control of the class. We started changing the process where we take the teachers to go and learn how to use the tablets first, within a safe space, where the teachers work together to learn the tablets so they will be experts."

He says another challenge they needed to navigate was that the children would play games during a lesson.

"Observing that, we installed a broadcast button where the teacher can control the tablet from where they are... All of this is learning and designing."

Because the devices are content agnostic, they are versatile enough to be used in schools anywhere. Kamau says they are in schools in Kenya, Rwanda, Mexico and places as far as Solomon Islands, located off the coast of Australia.

The team has recently introduced Moja, a free public WiFi network which offers anyone within range of the signal a connection to the internet for free where they can watch shows, listen to music or read books from the stored content on the Brck network.

He says for him the work that they do is not about ego or building Silicon Valley levels of wealth. He says for him the power of BRCK is a demonstration of how powerful design can be used as a force of positive change on the continent.

"For me that is the power of BRCK and the power of design. It is designing for people. The most powerful thing you can do with design is to do good.”

But computers were not always part of his world.

Growing up in Mathare in Kenya, computers represented a world that was far from his own.

He remembers visiting the city and looking admiringly as women in glass buildings typed away behind computer screens. He never saw a world where he would be one of the people behind the computers. Instead he focused on playing soccer as a way out of the township since his mother could not afford to take him to university.

He even made it to the Kenyan national team as a goalkeeper but had to stop playing football when he realized the football federation was broke and could not afford to pay its players.

“I can’t play football because it won’t pay me. I cannot go to college because my mom cannot afford it. I had nothing to do, so I enrolled on this programme ran by these ladies from the Netherlands.”

This was in 1999. The programme, called Nairobits, was the first free digital design school ran by a Dutch organisation called Butterfly Works. "The first time I used a computer I was super fascinated because you type in commands and it does what you want," he says.

He was in the programme for about two years where they learned how to build websites but also did excursions to art centres and museums around Nairobi learning more about urban planning and design.

When the opportunity came to design a website for the Dutch embassy, Kamau and a friend called Wilson decided to pitch.

"We’d never done any websites before" he says.

But when he got to the meeting at the embassy he explained: "The difference is for us this [ the job] is life and death, for the others it’s just another job. This guy took a chance on us. We got an opportunity to make the Dutch website. My friend Wilson and I worked our butts off."

He says on the day they had to present the final website they had worked through the night and only freshened up a bit just as the clients were arriving. The client was impressed and the two friends made $600 on that job.

"For me it was a big deal. It was a lightbulb moment."

Kamau went on to spend a few years training young people in computer skills before moving to the Netherlands and later Germany working in the tech sector.

"In Berlin I was working for this design firm and we were doing projects for Hugo Boss and governments like the Swiss government. I started getting into human-centred design. This is about understanding who you are designing for and making them part of that process because good design is design with people."

In Berlin, he got to work on the Hugo Boss compliance university, which provides training and development measures to the company's employees around the world.

"If you walk in a Hugo Boss store in Milan, you should have the same experience as if you are walking into a store in New York or in Berlin. And that means a curation of these experiences. It starts with understanding the customer and it touches on everything from the smell when you walk in, the light, spatial and environmental design. There was so much research. I was amazed at this approach."

Having learned about this approach to design he decided that it would be best to apply it back at home in Nairobi. Of that decision he says: “To leave a job that gives you money is a big thing. I am not a guy with a lot of degrees, so it was a big risk.”

Back home he set up Africa's first UX lab for start-ups as part of iHub, the non-profit established by Erik Hersman and Juliana Rotich of Ushahidi.

They had thousands of members who were starting lots of businesses but the success rate was very low. "I was convinced that this was because they were not using human-centred design. So you have people sitting in a room writing code and making something to help the woman selling vegetables but they’ve never even met her."

He adds: "The lab had a two-way mirror where I ask designers questions about their design process. Then I bring the person you are designing for, for example, the lady selling vegetables. I understood that when you start the design process you think your product is great. But when you see her [the vegetable seller] struggling you realise you designed it for yourself."

He says the lab ran on a Robin Hood model where they did consulting work for big clients with an interest in emerging markets like Google and Mastercard. Part of the profits were reinvested back into the lab to ensure that start-ups could access it for free.

“My interest is not my ego, my interest is to help with design."

His career trajectory and the success of BRCK through using human-centred design is a testament to not only the power of design and technology for social change but also of the impact that driven individuals like Kamau can have in effecting that change.

Watch Mark Kamau's Design Indaba 2018 Talk here: