Mere hours after American entertainer Donald Glover – aka Childish Gambino – dropped the music video for his newest single, This Is America, it became exceedingly clear that the hard-hitting, Hiro Murai-directed visual had broken the internet, so to speak.

Receiving over 12.9 million views in just 24 hours, it had gone more than just viral; Twitter users quickly turned screenshots of the video into memes, think-pieces were churned out and published en masse – and even outlets like CNN and Fox News invited panelists to offer up their takes on the release.

“These days everything is audio-visual,” the vice president of creative at Sony Music, Mike O’Keefe, told The Financial Times of this phenomenon. “Music doesn’t exist in isolation.”

It’s an accurate assessment; if there’s an art form that seems to be having a moment right now – albeit one that doesn’t yet seem to be approaching an end – it’s the music video. Today though, this traditionally promotional device has developed into something much more complex, and has emerged as a vehicle for artists and directors to craft fully-fleshed creative identities for themselves.

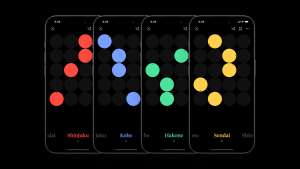

Consumption of the music video has also drastically changed. MTV is no longer calling the shots in terms of what they should look like, and the advent of smartphones, Snapchat, YouTube, and Instagram have blurred the lines between still imagery and video, allowing artists themselves to elevate the medium to new and unexpected levels.

“People want something that is going to emotionally excite them,” O’Keefe says, “With [the Childish Gambino video], its execution is fantastic, and there’s the political statement of intent; it’s something that has significance beyond the music.”

While the visual album and music videos have been a part and parcel of the consumption of popular music for decades – think Michael Jackson’s Thriller and Prince’s Purple Rain – it was the surprise release of Beyoncé’s self-titled fifth album in 2014 that really set in motion the modern movement.

Featuring 14 tracks and 17 videos, Beyoncé united music and film in ways few had witnessed before and the album was heralded as ‘boundary-pushing’ and pioneering – from both a sonic and visual perspective. “I see music,” the artist said in a video announcing the album on her Facebook page. “It’s more than just what I hear.”

Soon after that, Frank Ocean dropped Endless, a 45-minute-long visual album. Less than a year later, Florence + the Machine’s third album, How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful, was released alongside a series of Vincent Haycock-directed music videos that, together, formed a 47-minute long short film. Then, in 2016, Beyoncé released Lemonade.

A 12-track album and a 60-minute long HBO film, Lemonade featured spectacular imagery rich in symbolism, established a public, emotional narrative for a famously private persona, and had an unparalleled cultural impact. “Even if Lemonade is all an elaborate hoax, dreamed up by a pair of cackling Illuminati,” one reviewer for The Guardian wrote, “it is still nothing but magnificent.”

Visual releases like Lemonade have been immensely lucrative for certain musicians but, even more importantly, it's also proved to be a powerful medium for taking control of their own narratives. Beyoncé has not given an interview in years. Frank Ocean is notoriously elusive. Still, there’s no confusing their respective messages: hers, a sex-positive, feminist manifesto; his, an esoteric rejection of conformity.

“Ocean and Bey directed each film by themselves,” writes Consequence of Sound’s Michael Roffman, “making these direct visual counterparts and representations of their music. Nothing was compromised. Nothing was altered.”

This creative direction that has not eluded the consciousness of South African artists, with many choosing to follow suit and experiment with eye-popping, highly controlled visuals that compliment their already formed personas. In this way, they are taking command of their own stories and insisting their audience sees them as they seem themselves.

Take South African hip hop sensation, Sho Madjozi – real name Maya Wegerif. The Limpopo-born, Tsonga rapper released her debut music video for Dumi Hi Phone in December 2017 to rapturous fanfare. Fantastically colourful, unapologetically feminine, and boldly imaginative when it comes to its depiction of South Africa's physical landscape, the music video proactively and firmly establishes Madjozi’s persona as a defiantly proud, young Tsonga woman.

Madjozi has also demonstrated a remarkable amount of control when it comes to her own image and how it is presented, echoing the formulas being utilised by big, international musicians. Largely shot by her photographer partner, Garth Von Glehn, both her music and persona feel exceptionally authentic and deservedly self-centred.

“Right now, African art is about Africans taking charge and being at the centre of our art,” she said in an interview with Channel24. “We're making art for us now, and taking that to the world, as it is, as we are.”

More powerful and complex than ever, the music video has clearly evolved. They’re, to a larger degree, in the artist’s hands to craft and are starting to be developed in ways that are changing our understanding and consumption of music. Richer in story and highly effective in their communication, today’s music visuals dismiss tradition, creating new expectations for artists looking to connect with their listeners.