First Published in

If you could have a superpower, what would it be? John Bauer has made his choice and it’s the ability to transform objects into their ceramic replicas. Knitted hats, stuffed animals and a six-sided Buddha cube, Bauer’s turning it all into china. But doilies are his specialty. Antique shops, crochet and croquet clubs, church sales, and fleamarkets all know Bauer as the guy who comes for the doilies. And he’s a big spender – as far as century-old crochet collecting goes. One time, he snarfed up a stack of 189 doilies – exquisitely sewn cloth pancakes – adding to his collection that tops 1 000 in total.

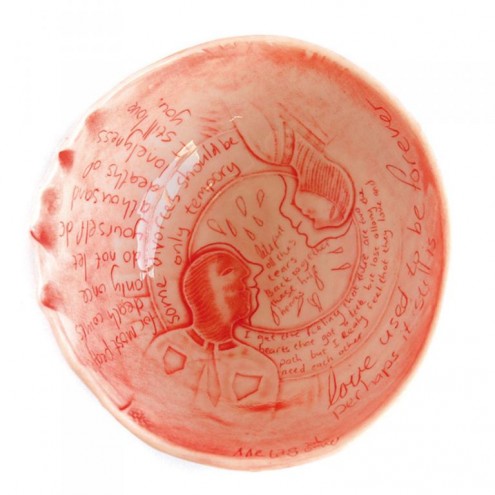

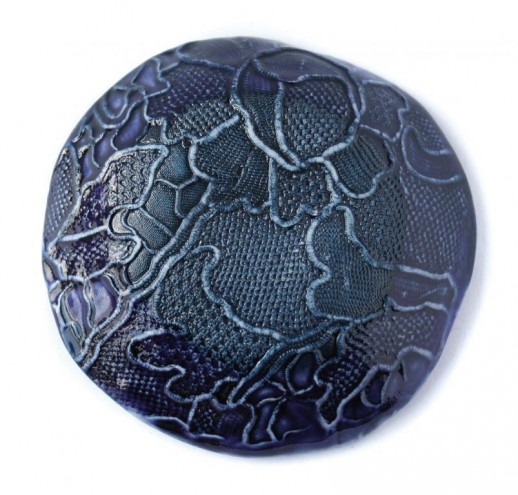

Using a self-invented mould and a secret method he doesn’t describe even to someone as clay-clueless as myself, Bauer transposes each lapel and tassel of a doily onto porcelain products, mainly heart-shaped trinkets and thin bowls no bigger than half a grapefruit. Sometimes Bauer floats a doily design behind another image that he has made on the clay, often a portrait, and the result is a layering of activity in the bowl, a visual narrative that complements the rather touchy-feely poetry etched in by hand.

“I’ve essentially found a way to do for craft what Photoshop pioneered in terms of layering, repetition and opacity,” explains Bauer. According to him, the moulding process is so sensitive that each thread and fray is replicated and renewed in ceramics, without damaging the ancient doily at all. And he’s right. In one bowl, I see the hairs on a hare’s tail show up in their varying thicknesses and I’m struck by the seamless, almost photographic quality of the mould.

These items do well locally and sell wildly overseas at cutesy outlets like Anthropologie. In fact, it’s thanks to a recent mega-order from the trendy lifestyle chain that Bauer’s ample Claremont house is now brimming with work. “When the Americans got hold of me, they took enough work in the first order to pay for the next 18 months of my life.” Who needs a Michaelis BFA when you’re making Forex? In fact, Bauer is a self-trained potter who works prolifically and industriously from home and may even describe himself as a happy craftsman.

“I used to run out of materials and had to actually stop working because of it,” he recalls, “but now I can just keep buying more materials and work away merrily. I’m not restrained in any way.” Indeed, if idle hands do the devil’s work, Bauer is doing extra credit for god. Then again, with the repetition of some of Bauer’s pieces ad nauseam and the dearth of open surface area in the house, one does wonder if restraint might not be the worst thing in the world. Nevertheless, there’s no dismissing the verve with which Bauer discusses his work, the work itself and his recent commercial success.

The bowls are delicate china and Bauer shades them with trippy blues and greens that certainly recall drugged experiences but also contrast well with the creamy three-dimensional outline of a meticulously woven doily. Indeed it is the almost unbelievably accurate transfer process that adds beauty and maturity to the bowls and thin heart slabs. As we sit on a sea-glass-blue couch in the living room and drink tea with mint from the garden, Bauer shows me some doilies before they were immortalised in clay. This particular one is from the 1820s and its simple and balanced arrangement of heavy triangles and semi-circles make it typically Afrikaans. I think about the Voortrekker Monument in Pretoria and see its chevrons and starred front-piece stomped out flat into a lace coaster. The Afrikaans doilies differ from the Portuguese ones, which are frillier and more ambitious, evoking images of Spanish moss, hoary bogs and the Portuguese Fandango.

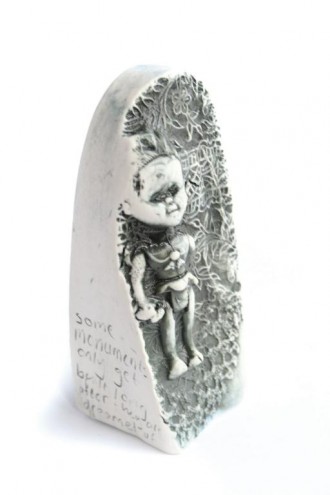

Bauer explains his rather long-term interest in preserving these doilies as a fragment of history: “The workmanship is incredible, however, the piece itself is ageing and is not going to be with us that much longer – maybe another hundred years at the most. Once I’ve taken a mould of it and put it onto a bowl, I can recreate the piece 1 000, even 5 000 times.”

If the bowl smashes, Bower says, its shards will reveal to future civilisations that the original design was made from thread. This will enable our offspring’s offspring to re-engineer the craft processes we used in much the same way that we have done with the discovery of the terracotta warriors in China. There, the emperor’s army was cast in clay and therein preserved some of their intricately woven rope armour. Besides looking out for the careers of future archaeologists, Bauer’s process is also about taking an artefact out of its conventional (and dying) medium and reinvigorating it in another less likely one. His informal crusade is about recognising and preserving human products that are painstakingly handmade and not mass produced: art, perhaps.

Is it, though? Even though Bauer has shown in top-notch galleries, he doesn’t see himself as an artist. Standing over six foot tall in something like hiker’s edition Uggs, Bauer has unruly hair in a loose ponytail and wears blue-jeans and layers of musty sweaters. “I’m really just a craftsperson. I wake up in the morning and perform my craft activities.”

I return to the distinction, if unnecessarily made, between arts and crafts as I’m curious to get his take on it. I suggested that perhaps “craft”, with its folksy connotations, contributes a sense of perpetual creativity and benevolence into First-World apartments, spaces within cities that may be devoid of a “living culture” themselves. Is the new craze for collecting craft-work (in South Africa) the modern-day equivalent of shooting a rhino and mounting it above the mantelpiece? Have developed nations identified, in handiwork, yet another indigenous resource to poach?

But no, Bauer’s happiness levels are too high to be ciphered off by my cynicism. “It’s very fashionable to be the victim, but my interpretation is different. If the beer pot maker isn’t enjoying himself and if the New York people are forcing him into making pots, then it’s a bad thing,” Bauer says and insists that he’s happiest when his hands are in clay and that born crafters often feel the same.

As for art: “Artists are people who are born crafters but are moulded through education and intellectualisation. I don’t think that concept really matters,” Bauer claims, rather emphasising what one feels when making the art. “So many artists hate when they’re creating their art. That’s why you’ve got this tortured art on the wall.”

Bauer believes that people collect craftwork because of the creative energy it gives off. When someone acquires craft-work they establish a personal connection to the handiwork and revel in the piece’s uniqueness. In Bauer’s case, his technique of casting doilies into porcelain is a process that is really one of a kind.

Before he shows me into the kitchen for cake, Bauer repeats that he only works when he’s enjoying it and that everything he does is engineered to encounter happiness. Looking at the 50-odd ceramic magnets on the kitchen fridge, John Bauer is very happy these days and, in his occasionally stunning work, one could see his mission as distributing little nodes of creative happiness all around him.