The drawings in this gallery are the result of a design studio, Unit 1, run in the University of Johannesburg’s Graduate school of Architecture. Students were asked to consider the theme of infrastructure in the city of Johannesburg: the “harder” infrastructure, which join (or divide) the city’s parts, and the “softer” infrastructure, which consists of the people-driven networks that shape the ways in which a right to the city and region is negotiated by its users on a daily, often precarious and unequal, basis.

Architect, artist and lecturer Alexander Opper headed Unit 1 with the assistance of Lorenzo Nassimbeni as a drawing representation specialist. 17 students participated in the studio. The collaborative studio, driven by a drawing-as-seeing methodology, encouraged a simultaneous re-valuation and re-evaluation of drawing as the life-blood of architectural thinking, research and practice.

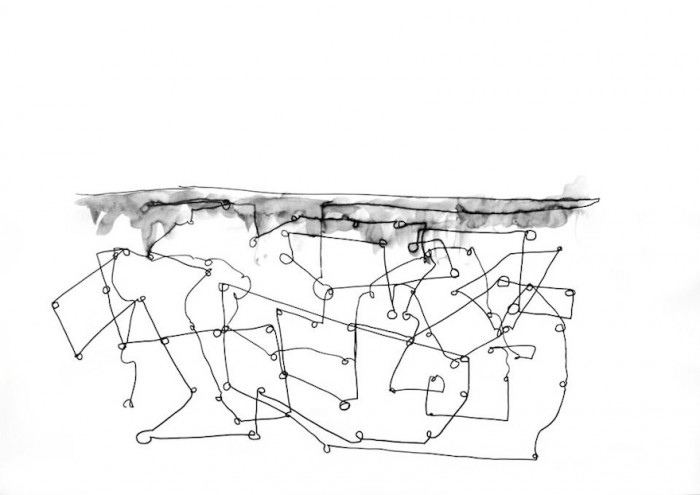

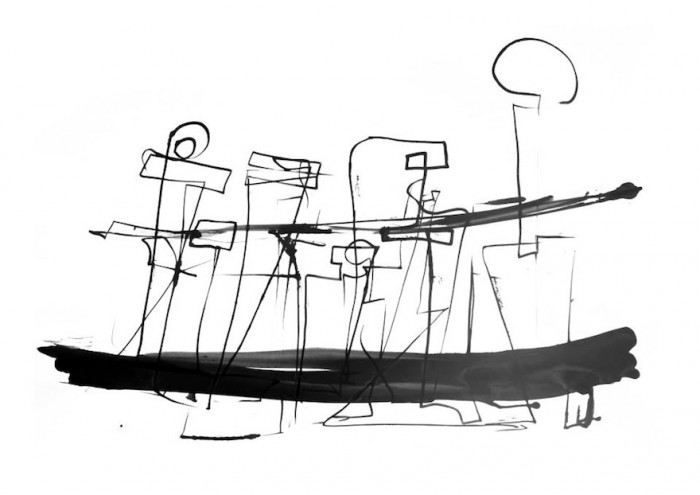

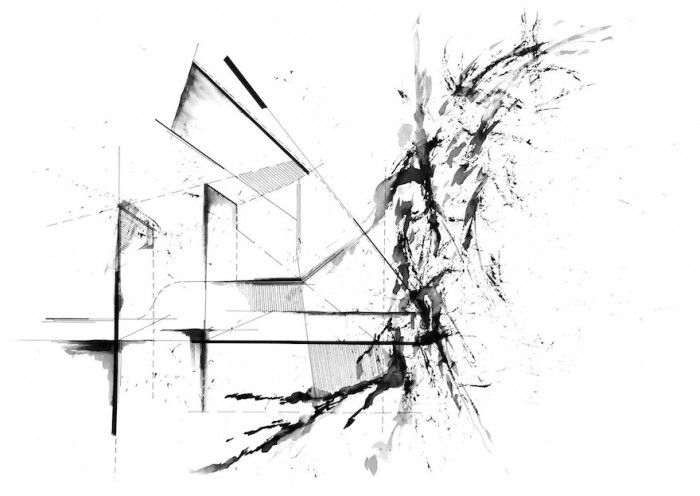

The projects shown here are demonstrations of how students trusted in an intuitive drawing process, guided by carefully structured briefs and workshops set by the studio’s leaders.

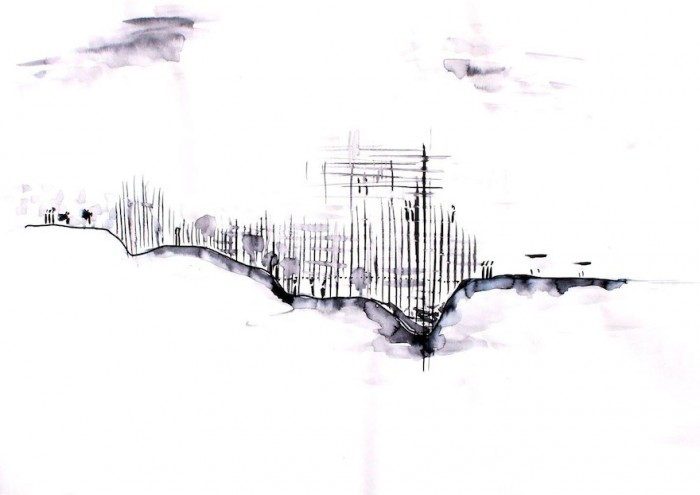

The chosen Johannesburg site for the investigation was Main Reef Road (MRR, also known as the R29). As its name suggests, this road topographically echoes the subterranean seam of gold that catalysed Johannesburg into existence. This currently underexploited asphalt strip runs east-west and, similar to the way a river or body of water in most other cities would do, has inadvertently defined the morphology of the region. In the case of greater Johannesburg, MRR is the functional thread that loosely links a sprawl-driven conglomeration of mining towns. MRR – said to be the longest road with a single name in the southern hemisphere – in all its raw understatement quietly represents a more low-key register of what the skyline of Johannesburg‘s Central Business District achieves as an obvious visual translation of wealth. The chosen road served Unit 1 as a lens of exacerbated possibility, a stage for the questioning, testing and stretching of what “infrastructure” might mean and look like as we dive headlong into the increasing urban complexity of the 21st century.

Infrastructure is often understood as the basic organisational and connective elements needed for a society or city to function effectively. Infrastructure can mean roads, bridges, water supply, sewers, electrical grids, and telecommunications; it can also refer to more typological, architectural building blocks such as hospitals, schools, factories, etc. Unit 1 took a broader view of infrastructure by zooming in on often-overlooked and hidden elements of a society and the ‘softer’ and more flexible nature of “people as infrastructure”. The expression is borrowed from Abdoumaliq Simone’s important 2004 text by the same name. MRR is the meandering line – a 1:1 scale drawing of sorts – the hard infrastructural backbone which ties together a host of seemingly ad-hoc and disparate phenomena. These range from the identifiable programmatic Johannesburg patchwork – residual mine-dumps (unintentional landmarks); theme-parks; middle-class gated communities and so-called informal settlements – to the more elusive networks and aspirational moments, and movements, of people, the “life-worlds” of individuals and groups included or excluded in varying degrees from what could be referred to as the Johannesburg Dream. In the tradition of Johannesburg’s exploitative and exclusive history – physically, as a result of the discovery of gold and socially, via the engineering of difference through apartheid – MRR displays an ambiguous quality: Whilst it bridges the east and west of the city and the larger region one simultaneously encounters it as a meridian-like divider, between the poorer and marginalised South and the disproportionately wealthy North of Johannesburg.

Despite its shortcomings, MRR has real potential to re-invent itself as a more rhizomatic mechanism, an urban weave of connectedness and access to social and economic opportunities. Its currently loose line, and the blurry ‘uitvalgrond’ (surplus-ground) conditions flanking it, exhibits the potential to exploit its formlessness, not towards simplistic form, but towards processual integration, bridging and connection; toward a condition of infrastructural (hard & soft) integrity and inclusion. MRR has the prospect to re-connote and recodify itself beyond Johannesburg’s often overly simplistic branding rhetoric (for example, ‘Corridors of Freedom’), as a reanimated original element of powerful urban identification, both symbolically and physically.

In Unit 1 the typological over-simplification of the urban descriptor, ‘road’ was thickened into, and catalysed towards, regional/landscape/architectural hybrid propositions. Road may be, to consider one example, extended to ‘bridge’, as something which is able to span, link and connect in a different way. The currently marginalised and underexploited character of MRR was used to un-draw, reimagine and re-draw its possible futures. The unit aspired to re-vision MRR’s various flows, as integrative, and countered the fallout of its dated and more divisive DNA. In this vein, Unit 1 continued an interrogative rethinking of architectural teaching and learning tested by Alexander Opper over the last nine years at UJ/FADA (Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture), of “’folding’ the [architectural] studio into the field”, and productively “undoing” architecture. The small selection of projects you see here represent the drawn relationship between body, hand, eye and mind, in dialogue with the larger and more specific social, physical, cultural and economic project context(s).

The architectural investigations and propositions which Unit 1 stimulated in many cases reveal some of the often hidden and undervalued forces, structures and systems that underpin the city and region (MRR spans more or less 80km between the mining towns of Springs, in the east, and Randfontein in the west). The road-as-map served Unit 1 as a permissive framework for a multiplicity of possible interventions at the metropolitan, district and architectural scales, offering students a broad range of opportunities and possibilities to test and redefine existing understandings of “infrastructure”.

Please visit the "Unit 1, UJ" page to see more. Finally, a highlight of this year was the successful public auction of original drawings by the students and leaders of the studio.

* The project title borrows from and extends on two important existing texts. One older: Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Stephen Izenour’s "Learning from Las Vegas" (1972); and one more recent, and closer to home: Lindsay Bremner’s "Writing the City into Being" (2010).