First Published in

JM Coetzee’s Nobel and Booker prize-winning novel Disgrace has the power to break up a dinner party. Google’s image-search function creates a seemingly “democratic voice” by rating pages on popularity. Writer, playwright and critic Stacy Hardy and interaction designer, multimedia artist and software developer François Naudé have combined these two disparate ideas to create "dis.grace".

By matching each word of Coetzee’s novel with its equivalent top-rated image on Google, dis.grace raises a number of questions mostly left unasked. Does the move away from old literary forms towards new digital and image-based culture signify illiteracy or rather a different literacy? What is the relationship between authorship and authority? Are texts translatable across cultures? Does translation entail a politics of universality? What are the impacts of globalisation and consumerism on both personal and national identity? What is the role of art in a culture where the instantaneous proliferation of images and codes in everyday life has led to a breakdown in meaning? What are the implications on society with the disappearance of meaning?

While it may all sound conceptual, the end result is disarmingly effectual. At a scale of large-print words, the paragraph-aligned images immediately invite one to engage in the act of reading, glancing from one sequentially placed word to another. Initially, it is all meaningless but it is relatively easy to identify words such as “a” or “the”, based on frequency. Right away the slippage becomes apparent – after all, what image would one imagine these articles to be denoted by? Jumping between these identified images, one then starts to subjectively ascribe meanings to the images in-between, based on one’s own predilection towards Coetzee’s text.

Of course, based on the experience with the articles, one is already aware that these images are not translatable according to one’s personal logic. Nor even homogenised logic – with only 2.5% of the world’s Internet users coming from Africa, even direct references to the continent in the novel are mostly translated into images that originated in the West. But that doesn’t stop one reading the tableaux like a mirror. Supposedly “shunning both the authority of the author and the omniscient narrator used in the Western novel as the equivalent to the intruding coloniser,” the project only identifies the coloniser in all of us.

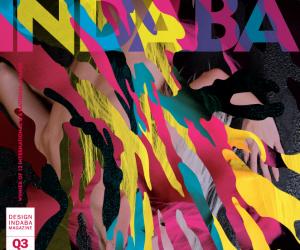

Besides the operative, dis.grace has a number of media manifestations. The program itself can spit out different versions of the book according to how the image ratings on Google change. A video work links the images to a voiceover of Richard E Grant from his narration of the audio book. And the gallery exhibition comprises 200 high-resolution printed works, each priced according to “hot” topics such as crime, sex, rape, violence and racism. This pricing structure highlights and satirises the pathologised view of Africa presented by the global media, which often chooses to focus only on war, famine and genocide in its coverage of the continent.