Self-taught photographer Deepti Asthana grew up in the small Indian town of Uttar Pradesh. She first worked in I.T. while also filling the creative void in her life by experimenting with travel, fashion and wedding photography.

However, these genres didn’t quite fill the gap of a need to create work that made an impact. Passion soon turned to profession once she’d found her cause and immersed herself into it entirely.

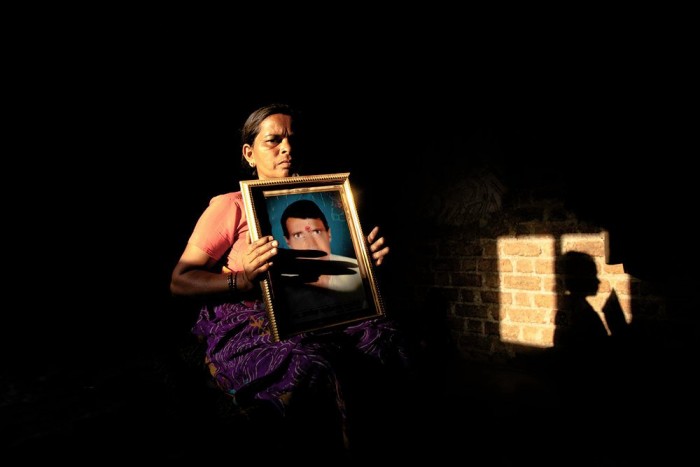

Her motivation stemmed from a deep-rooted dissatisfaction with the largely unseen ways women are mistreated in India’s rural areas. Having herself grown up in a small town, she was exposed to this first-hand, particularly in the way her mother was treated when her father wasn’t around.

“The need to alter the narrative that women are weak or helpless, to one that acknowledges that every girl is a powerhouse in herself influences my practice,” she says.

Her ‘Women of India’ series almost established itself organically as she was finding her own voice.

On a trip to Mithapur, Gujarat, she happened upon a thirteen year old girl, Bharti, laboriously working the salt pans, completely exposed and vulnerable to the associated hazards. Asthana would soon learn that Bharti’s father demanded that she earn a living if she was to continue living with him.

She was resolute in her goal to bring stories like Bharti’s to the fore, revealing the realities of young girls robbed of their childhood and rights to education.

While feminism and gender issues are finally a part of the wider, global conversation, Asthana says this hardly extends to rural environments. And she points out that this isn’t merely a uniquely Indian problem, but a global one.

It’s what underpins the value of the work she’s doing: “The situation in a village in India could very well be of that in a village in any other country, which is why this project becomes even more relevant and important."

The poignancy of her work is a result of her pure connection to her subjects. She says it’s important that she not be seen as an outsider. She puts in the time to blend into people's lives to get a true glimpse of life through their eyes, “that connection I form with them is what lends intimacy and honesty to the images I make.”

Her work has not gone unnoticed.

In 2017 she was nominated for the Joop Swart Masterclass, an annual event organised by World Press Photo. She received a grant from the Serendipity Arts Foundation to document a fishing village in South India.

This year she became a recipient of a Focas Scotland grant, along with the opportunity to exhibit her work across India and Scotland.

This piece was adapted from an interview by Ritupriya Basu for Design Fabric in India.