The Syrian civil war, which resulted in the uprooting and displacement of millions of people, is why neighbouring countries like Lebanon have seen a dramatic increase in the number of refugees seeking asylum in their states. Over 600 000 of these refugees are children who have to come into refugee camps that are not equipped to provide a vibrant and safe atmosphere for children. An expert on youth concerns in war and post-war countries, Marc Sommers, says that children often become invisible within humanitarian programmes that provide help in emergency situations.

As a response to these issues, IBTASEM playground project was launched in August 2015, with a particular focus on refugee children. This project is founded on the belief that children have a right to an education, to feel safe, to play and to develop confidence in themselves. IBTASEM advocates for the design of playgrounds within war emergency response, arguing that playgrounds represent a vital role in providing relief for refugee children who may suffer from psychological trauma and development issues.

By involving children from the beginning to the end of the project, the IBTASEM design approach was able to achieve two things; a playground tailored to children’s particular needs and one which gave children a sense of ownership.

“We had to do a lot of research about the kinds of spaces that we wanted to created in relation to the act of play”, says IBTASEM’s executive director Riccard Conti. The organisation didn’t want to merely provide the children with playing facilities such as swings and slides, but rather to develop spaces within the playground to target different areas of child development.

Examples of these spaces are:

The Active Space or everything related to physical activities such as sport

The Private Space, an environment where the children can be relaxed and enjoy themselves

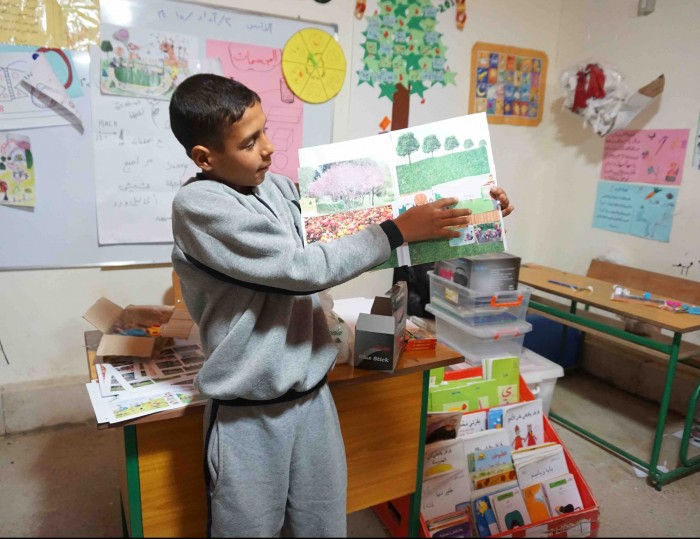

The Educational Space, which are conducive spaces like classrooms where teaching and learning can take place

To ensure that project goals were met, a two-phase design-build workshop was hosted by the organisers. The first phase of the workshop focussed on the building structure of the playground. Locally produced materials such as timber were used to build the playgrounds. The kinds of materials used were of high concern to the programme organisers because they wanted to ensure that they used materials that could be easily assembled, disassembled and transported. The second phase of the workshop focussed on playground components and finishing. This stage allowed the children to communicate their desires for the playground through facilitated exercises that encouraged brainstorming, creativity and even drawing to begin conceptualising and bring their ideas to life.

Talking about the impacts of the playground on the children, Joana Dabaj, who is the principal coordinator of IBTASEM, says, “Syrian refugee children were able to develop healthier ways of self-expression”. Before the playgrounds were built, organisers say that they observed a lot of fights amongst refugee children on the camp gravel sites which could have been a result of all their trapped energy.

Refugee camps are often harsh and restrictive environments that don’t aid in the development of refugee children, therefore the IBTASEM project can be seen as a catalyst, triggering the awareness of the much needed safe spaces for refugee children to grow up.