Part of the Project

First Published in

Ross Lovegrove: You and I have stayed really good friends, because intellectually there is a lot that we share. If I want to see an exhibition with somebody, I’ll always call Fernando because we have a very good level of discussion and a mutual curiosity. Personally I have great respect for what you do. You know your art form very well and refuse to be shaken or stirred – James Bond terminology – by others and movements. You are aware, but you stay true and just keep refining what you do. Would that be fair to say in terms of your own path?

Fernando Gutiérrez: Yeah. It all began for me with magazines. Magazines are incredible social tools. The magazines that I worked on were all related to entertainment and the arts. I’ve continued working in that world.

Ross: Do you see the magazines and the other work you do, the books especially, as an art form?

Fernando: Yes. Magazines and books, if they’re done beautifully and the subject is going to last forever.

Ross: On sale at Christie’s there was an edition of Interview magazine in an acrylic box with Andy Warhol on the cover, drawings by Antony Gormley and Tibor Kalman inside. So there is this idea of the historical and social value of magazines. Do you see it in that way? Like when you were the art director of Colors, that was a very powerful tool at a very powerful time. But also a hard act to follow on from Tibor Kalman and Oliviero Toscani?

Fernando: I just wanted it to continue. It was an incredibly romantic project, of that moment and right for that moment. It still used very traditional ways of communicating – it was photographs on paper. But the visual language was still interesting and quite different. Now it’s a lot easier to do things in real time, which is a whole new way of communicating. I’m still very traditional in that way – I still believe in the book and the magazine.

Ross: Yesterday was the first time ever that I didn’t present a project to a client. I emailed it, which is outrageous for me, I always sit with a client. But I was ill, so I couldn’t do it and he said email it. Ugh. I didn’t get the chance to really explain the surrounding context of what I’d designed. Do you think the electronic medium has taken some of that mystery away or do people expect more from you?

Fernando: It depends on the way you’ve developed. I prefer, and that’s a good reminder, to always meet the person and be close. Because that’s the way I’ve always worked. The emailing side of things I just find too cold. I find it detached.

Ross: Don’t you think that some things appear, and through a sort of global consciousness, become inevitable. When in fact no one has really been asked whether they like that change, it’s just an inevitability. So what you have in publishing for example, is this paranoia that unless they go electronic, they’re going to lose out. It sort of accelerates the death, if you like, of the old medium.

Fernando: What the old medium needs is just a transformation. We’ve got to take the sensitivity of the old medium into the electronic. And right now that’s quite complicated because the digital is all programming and stuff, and things just get designed by default. The sensitivity, I feel is not there.

Ross: But it’s lost all tactility. I don’t want to get too romantic again but the whole physicality, from paper weight to quality of colour refinement.

Fernando: But even in terms of the content – take an interview for instance. Instead of a series of photographs, which is a very personal interaction between the photographer and the person being interviewed, now the whole interview is filmed to be displayed well on iPads and other new technolology.

Ross: Those tools can also be incredibly seductive. This is a golden age for people like me to be able to really show my capabilities, whereas in the past it came down to the gift of drawing or illustration, which is so old fashioned and very slow. Those drawings and sketches have been replaced in the public domain by computer imagery. A studio like mine, which is a very high-level state-of-the-art studio, is expected to deliver everything at that level. But what I try to do, what I pride myself on, is that the object that you see will always be better than the computer image – because of what you just said about graphic design and the fact that there still needs to be some tactile element. Like the staircase that I just did, you’ll never be able to understand the colour and the crispness on a computer screen. It’s the physical act of being with it. Like being with an animal or meeting someone famous that you’ve only ever seen on television, when you see them in reality, there’s another aura.

Fernando: I’ve known you over the years and I’ve seen how your work has evolved. I like that you’ve always looked towards the future. It’s looking at how your objects fit into an improved lifestyle. It’s making us think about our environment and how our world functions. Over the years, you’ve gotten more and more into this vision of the future that connects to now. I think it’s very interesting, the materials that you introduce, and the form and shapes of some everyday objects, some not so everyday. I can feel how it’s transforming, how a little object can become very very large.

Ross: I had a fantastic discussion yesterday with Konstantin Grcic about Black, his series of exhibitions. He loves the power of black and the opposite of nature, meaning the brutal nature of industry as an artificial force as opposed to copying a pebble on a beach. People perceive me as doing white and him as doing black. But actually, I do quite a few things in black. That’s why I sort of understand Konstantin’s approach. I understand it very well, I just don’t do it.

Fernando: It’s interesting that he puts out exhibitions that are not about his work, but more of a debate. He’s provoking debate.

Ross: Unless there’s enough debate, you’re never going to come up with some sort of treatise of observation that can ever move anything. We’re at 50, where we’re not young or old, and we can reflect back and also look forward.

Fernando: It’s a great age, a great moment, a crossroads in our work. I think I’m a bit younger than you but in technology terms, when I started working, there were no computers. So we are of the same generation. When we began, we had to do it ourselves or we worked with people that no longer exist anymore.

Ross: Now today, anybody in any country with visualisation skills and a laptop, can just put this stuff onto the internet. It’s so disposable, it’s incredible.

Fernando: The industry is bigger than ever. There’s more schools than ever, there’s more books being published on design than ever. It’s a huge business. I think there’s going to be a lot more people interested in design and buying design because more people have been educated about it. What I like to think is that these people won’t necessarily become designers, but will have a sensitivity towards design and know to use design in business and culture. Otherwise, the jobs just aren’t there. You can’t just go off and set up your own studio – you’ll get eaten up. Running a business in design is very hard.

Ross: People often say to me that design seems easy to me, like it’s effortless. Well it might appear effortless, but that’s only because I’m not speaking. But my mind is constantly questioning what I do because I’m a hard taskmaster and you’re supposed to get more and more relevant, to get better at what you do. I went to an incredible lecture the other day by Patrik Schumacher, the partner of Zaha Hadid. It was a new manifesto on architecture, a Le Cobusier-esque treatise, “Towards a New Architecture” type of thing. He said that with the onslaught of computing ability and the way that young people have grabbed onto this tool, especially in architecture, a new process has evolved called parametrics. Basically what you do is the computer runs, like flapping a sheet in the wind and freezing it. Then the computer gives you the data to manufacture what you see from the materials. So I’m interested in relevance and the time in which I live, but I can see that there’s going to be an explosion of biodiversity because there’s just so many people designing.

Fernando: But what about the role of the client? For me, it’s very important to have someone who comes and asks you to do something. They challenge you. Propose to do something that is going to be groundbreaking.

Ross: They are few and far between. I don’t have many clients like that. I mean, I just had a meeting about doing an electric vehicle and I knew more than the CEO of the company.

Fernando: Because the idea of a good client is that he is smarter than you.

Ross: You don’t need the client.

Fernando: With the client it is also the dialogue around improving and making an idea and putting it out there. You need someone that’s brave. You and the client have to be brave. The client has to have a vision.

Ross: Most of the time there isn’t the time anymore to sit down with your clients in a pair of jeans socially and talk about, for instance, the use of water in bathing culture and sanitation. Just water, not a product. Because this is a higher philosophical position, it’s about water preservation, use and management, as opposed to style. It’s content over style that I’m after. It would be wonderful to reinstate the old model – slow it down a bit – and still be able to survive. And then to have more of a direct dialogue with a handful of really wonderful, innovative clients and grow with them.

Fernando: That is the old way of working. But the beauty of technology now is that you just don’t need as many people as before. Even with filmmaking, you really don’t need such a big team anymore. One could do a newspaper with a really small team and cover the whole world.

Ross: You could start a newspaper. Doesn’t matter what the distribution is. What’s next for you – any dreams, any big objectives?

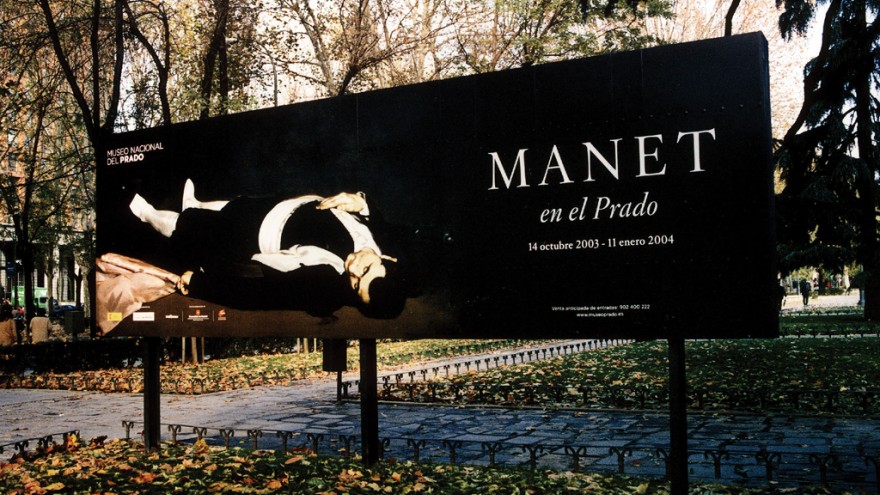

Fernando: In the principality of Asturias, a region of Spain, I’ve been helping to develop a cultural programme as well as the TV station for their local region. I find that very interesting. Another project is in the capital of Spain, Madrid, working on the main classical museum. Both of these things, they’re not directly about design, although that’s important for me in the project. They’re more about helping them to get people to interact with the product, which in this case is culture, and give them something to inspire them.

Ross: I like the way that you approach things like that, there’s enough slap in the face.

Fernando: Is there anything you wish you had designed? What’s your dream?

Ross: I don’t get up in the morning thinking I wish I’d designed those cufflinks. That doesn’t interest me at all. But a car… It’s because I see the car as a large product, I don’t see it as a car. I see it as both the icon of our civilisation or civilising abilities, and our demise. It’s an icon of pollution, but it’s also an icon of liberty and freedom. So to crack that one in my lifetime! I will also definitely work on another space programme. I’m interested in transportation at the moment – moving people: moving their soul and sensuality but also physically moving people. I want to grow as an artistic mind, a philosophical artistic mind and I will continue as the designer in whichever way that light falls on me. I’d like to keep the integrity to grow that way. My real soul doesn’t have to justify things through function or marketing, it’s really more earthy and primitive than that. My mind is in a deep past in order to create a deep future. It might not be understandable for people, but it will be. And you?

Fernando: For me it’s helping to develop and promote good ideas. Essentially giving good ideas the right help. Whatever those good ideas could be. It could be a magazine, a newspaper… I mean I’m very interested in what I said about this regional government, helping them communicate a series of cultural ideas to their public. It could extend to a whole country. However, there’s a political side that has no appeal and to get things off the ground, you do need good politicians that can help.

Ross: That’s it though – you want to step it up. Not because your ego gets bigger. It’s actually the fact that you can effect more, communicate more to people with a broader idea. It’s really tough some days to get up and think that I have to work on a door handle. I can. But I don’t think it’s a significant enough use of one’s experience. So you’re only as good as your client.