First Published in

Eve's apple, or what was left of it after Adam had taken a bite, quickly browned. (Everything browns in time.) And mud is brown. And our human waste is brown, which embarrasses us because it reminds us that we are flesh destined to melt into earth.

But the bright future is brown. Even as I write these words from the distance of California, brown is colouring much of our post-modern world. The world turns brown as citizens of this round earth discover one another, and fall in love with one another, and create children belonging to no distinct race or tribe or tongue.

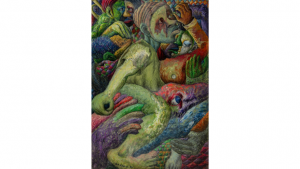

Brown is the best metaphor I know for mixture and impurity and post-modern eroticism.

Brown is not a primary colour - like red or like yellow. Brown is not even a secondary colour - like purple. To achieve a deep, rich shade of brown, you need to combine three or several colours. Indeed, when painters clean their brushes on the edge of a canvas, the resulting puddle or smear is often brown.

The ancient world often knew brown. Violence created brown, as well as the peaceable movements along the spice and silk routes. Brown thrived wherever strangers met, whether in battle or curiosity or desire for trade. In today's Muslim Middle East, you can meet green-eyed descendants of Christian Crusaders. Islands that have greeted galleons from distant continents - like the Philippines and Sicily - have long been brown.

In Latin America, brown dates from the colonial era when the New World Indian met the European and the African. In the lexicon of Brazilian Portuguese, there are today several hundred words for possible racial admixture. In Mexico, where I trace my own ancestral beginnings, the entire myth of nationhood is brown. Mexico describes the moment of its birth in the violent and erotic meeting of the Spanish conquistador and the Aztec Indian. From an act of rape came an entire brown civilisation, the "mestizaje."

But in the United States, where my Mexican parents migrated, brown was long a colour difficult to admit. Brown, not blue, was the colour of illicit love and drawn shades and family secrets.

Since the enslavement of the African, the United States was inclined to describe itself as black-and-white. Colonial slave-owners came up with a notion called the "one drop theory" to discourage racial intermixture. The one-drop theory proposed that, regardless of how light one's complexion or European one's features, a person was "black" if he or she carried a single drop of African blood.

Slave owners had economic reasons for fearing brown; the admission of brown would have undermined their control of the slave. Their terrible influence on the American imagination survived even into the late 20th century. It remained difficult for many African Americans, who were obviously racially "mixed" to speak of themselves as brown.

And do not forget the American Indian. From the earliest chapters of "New World" history, brown children were created from the marriage of African and Indian, throughout the Americas. Today, most African Americans freely speak of American Indian relatives -a Cherokee grandmother, perhaps, or a Sioux uncle or a Mohican great-grandfather. (The American frontier was brown, indeed.)

Today, young American people are broadcasting brown, turning brown into a song, a veritable menu (like the tofu burrito), an aesthetic. Children in California, where I am writing these words, routinely invent new brown names for themselves. I meet, for example, young people who call themselves "blaxicans" (African Mexicans) and "negro-pinos" (African Filipinos). One begins to see on their fresh, new faces, something of what Columbus surmised. For here are children who belong to no one part of the world, but to a world that is round.

Tiger Woods, the most famous golfer in the world, describes himself as being Thai and African-American (because of his mother and father respectively), but also "white" and American Indian. In Hollywood, Michael Jackson creates a rock video in which his face morphs into every face and race in the world, both male and female. And Madonna, the uncrowned queen of brown, yesterday impersonated Marilyn Monroe; today she is Eva Peron; tomorrow, she will be a geisha.

More interesting still, some of the brownest children I meet today are brown not just in ethnic or racial terms, not just in pigment, but in their souls. Racial intermarriage has joined foreign, even warring theologies and creeds in a single child's soul.

I can introduce you to a girl who calls herself a "Baptist Buddhist". My own cousins describe themselves as "Hindu Catholics". I even know a young woman named Jennifer who is (in her own words) the daughter of a "New York Jew and an Iranian Muslim." Some days, she calls herself a Jewish Muslim. Other days, she calls herself a Muslim Jew.

I suspect that religion will become the 21st century's notion of race. Religion will organise us and divide us from one another. So these children of brown soul could reconcile us to one another, or they could end up caught in an increasingly dangerous world.

For the last irony of our brown world is that we live at a time of mixture and retreat. As we mix in airports and on cable television, as more and more of the world confronts itself and is romanced by the foreign, as recipes and musical notes and theologies mix, there are some who will yearn for "purity" or fundamentalism. Even while others fall in love and produce even more brown children, there will come dreams of new borders in this brown, round world.

Author Richard Rodriguez is an editor at Pacific News Service, and a contributing editor for Harper's Magazine as well as the Sunday "Opinion" section of the Los Angeles Times. He has published numerous books, most recently Brown: The Last Discovery of America. In 1997 he received the George Foster Peabody Award for his NewsHour essays on American life. Richard Rodriguez will be a speaker at the 6th International Design Indaba, February 26-28, 2003, Cape Town, South Africa