First Published in

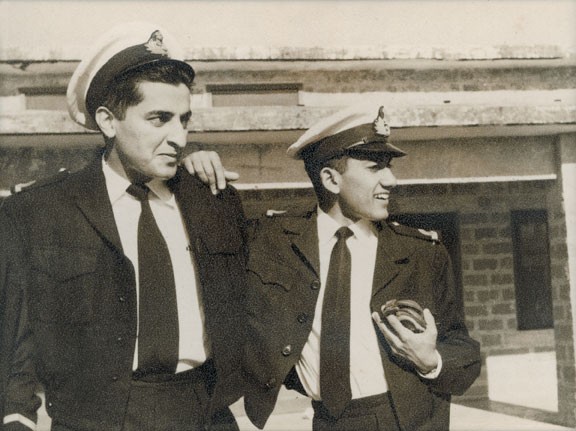

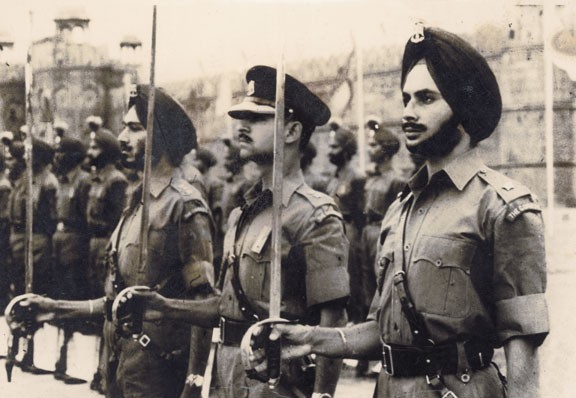

Ours were once simple, starched lines in olive and khaki with the odd burst of colour on turbans, or shoulder patches that reflected a regiment’s ethnicity or a squadron’s cavalier style. Though colonial by origin, these uniforms represented the spirit of an independent and optimistic new republic. Like the individuals who wore them, they had strength and character rather than shiny bombast. The look extended to aircraft and vehicles, all of which were smartly hand-painted and bore stately insignia. Even bureaucrats had a uniform of sorts – a short-sleeved “bush shirt” or the much-maligned safari suit.

Then things began to change. Political idealism turned into cynicism and began to infect all the institutions around it. A brand new republic soon regressed into a feudal state, run by power brokers.

In society at large, wealth and status began to take precedence over honour. By the time the 1980s and economic liberalisation kicked in, the Indo-Pakistan War of 1971 had faded from public memory and the military was regarded as an avoidable, cash-strapped career alternative. The top brass tried to glam things up and polyester, flash and tack started showing up everywhere. Service chiefs began to experiment with golden braids and stars, mix-matching American military insignia with the original Commonwealth look. Interior designers were hired to transform mess facilities into gaudy knock-offs of five star hotels. Cheap chandeliers and deep-pile carpeting started appearing in regimental dining rooms and squadron bars. Even camouflage patterns and unit emblems started looking a bit over the top. And news began to surface of dirty arms deals that involved high-ranking officers. A world of simplicity and strength had been turned upside down.

Today, the men and women in our fighting formations are still noble, courageous individuals who are ready to lay it on the line with no expectation of reward or even respect. Their commanders, however, look more like pot-bellied band-wallahs (marching band conductors) than spartan leaders. But there’s hope. The Air Force has started painting all its aircraft in a uniform, no-nonsense dark grey. And the Chief of Army Staff recently made it mandatory for all personnel – frontline or otherwise – to wear combat fatigues for at least one day a week. Perhaps it’s time for the military to get its image back.

Uniforms express ideals, or the lack of them.

Uniforms express ideals, or the lack of them. Ours were once simple, starched lines in olive and khaki with the odd burst of colour on turbans, or shoulder patches that reflected a regiment’s ethnicity or a squadron’s cavalier style. Though colonial by origin, these uniforms represented the spirit of an independent and optimistic new republic. Like the individuals who wore them, they had strength and character rather than shiny bombast. The look extended to aircraft and vehicles, all of which were smartly hand-painted and bore stately insignia. Even bureaucrats had a uniform of sorts – a short-sleeved “bush shirt” or the much-maligned safari suit.

Then things began to change. Political idealism turned into cynicism and began to infect all the institutions around it. A brand new republic soon regressed into a feudal state, run by power brokers.

In society at large, wealth and status began to take precedence over honour. By the time the 1980s and economic liberalisation kicked in, the Indo-Pakistan War of 1971 had faded from public memory and the military was regarded as an avoidable, cash-strapped career alternative. The top brass tried to glam things up and polyester, flash and tack started showing up everywhere. Service chiefs began to experiment with golden braids and stars, mix-matching American military insignia with the original Commonwealth look. Interior designers were hired to transform mess facilities into gaudy knock-offs of five star hotels. Cheap chandeliers and deep-pile carpeting started appearing in regimental dining rooms and squadron bars. Even camouflage patterns and unit emblems started looking a bit over the top. And news began to surface of dirty arms deals that involved high-ranking officers. A world of simplicity and strength had been turned upside down.

Today, the men and women in our fighting formations are still noble, courageous individuals who are ready to lay it on the line with no expectation of reward or even respect. Their commanders, however, look more like pot-bellied band-wallahs (marching band conductors) than spartan leaders. But there’s hope. The Air Force has started painting all its aircraft in a uniform, no-nonsense dark grey. And the Chief of Army Staff recently made it mandatory for all personnel – frontline or otherwise – to wear combat fatigues for at least one day a week. Perhaps it’s time for the military to get its image back.