First Published in

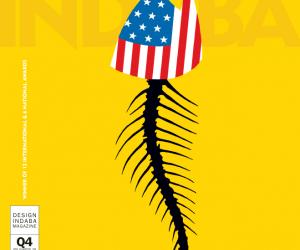

I spent a year of high school as an exchange student in a leafy suburb of Chicago. Back then the United States still had an almost mythical reputation for being the “land of the free”. So free that my host family didn’t lock the doors to their house. It seemed crazy at first, but it wasn’t the only house with an open door. A friend of mine couldn’t remember where he kept his keys when he tried to sell his house – in the two years his family had lived there, they had never locked the door.

Clearly, a world in which people don’t lock their doors and visit each other when they feel like it is a better place than one with high walls and carefully scheduled appointments. Open doors go hand-in-hand with good neighbourhoods. The same is true for knowledge. Sharing ideas with others creates a sense of community. Culture evolves common identity by passing stories and songs from generation to generation; and scientific progress depends on researchers scrutinising and improving each other’s work. A good idea becomes more powerful when many people know it.

Sharing nicely is not a new idea. We know examples of gift societies and collectively owned natural resources that took place hundreds of years ago, and more recently open innovation processes helped increase steam engine efficiency during the industrial revolution. However, much of this seems to have been forgotten and ideas of community and sharing have been replaced by a cult-like focus on individual achievement. So much so that giving knowledge away can seem like a revolutionary new concept today.

A few things have changed recently that make sharing more important. Technology – computers and the Internet – enable many of us to distribute ideas faster, more cheaply and on an unprecedented scale. But more important than the technology itself is the way it has changed the social norms of Internet users. As we experience transparency and the ability to participate online, we start to demand the same offline. The Internet has reminded us what it could be like to live with open doors.

There are plenty of examples, from software and fashion to letting travellers stay on your couch. Open source software projects have created the applications that run most of the Internet, including some of the largest websites, like Google and Wikipedia. Wikipedia itself has become a vast collection of human knowledge, written entirely by volunteers – “Anyone can edit” is not a marketing slogan, but a production model.

In fashion, there are companies like Threadless that let users design T-shirts or RYZ.com for shoes, and the community decide which ones get produced. Profits are shared between all contributors. Through the Open Architecture Network, architects are sharing blueprints and designs to address some of the housing problems in developing countries.

Sharing does not only work for products and design, but even for accommodation or public policy – the couchsurfing community connects travellers who end up staying with each other and often become friends. Putting the public back into public policy, TheyWorkForYou.com makes voting records of political representatives in the UK easily accessible, helping voters make informed decisions the next time they pick a candidate.

In order to design for this sharing economy, we need to better understand how it works. What are the common characteristics of the projects mentioned above, and how can they be replicated? These are important questions for everyone: from social movements trying to create a better world, to companies needing to better understand and serve their clients’ needs.

The fundamental drivers of the sharing economy are the concepts of openness and participation. Open is often used as an adjective, but more appropriately describes a process that is participatory and collaborative. For example, in order for software to be “open source”, developers agree that their contributions are licensed with four rights that allow others to participate: the rights to use the software; to study it; to make modifications to it; and to redistribute the results (these characteristics are also referred to as the four freedoms, defined in Richard Stallmann’s free software definition).

The four freedoms translate well from software development to other processes. Processes have to be transparent so that potential participants are able to see how things work – and also how well they work. They must be permeable, with low barriers of entry so that people can float in and out of the community. And they need to be malleable so that participants are able to improve them.

While the sharing economy is often associated with ethical values or political convictions (critics mention communism, supporters speak about meritocracy), it remains inherently pragmatic, aiming for efficiency rather than belief. Projects may start with a few people who are trying to create something that they need, realising that it’s easier or more fun to do it together with others. More often than not, these people know more about the problems they are trying to address than anyone else – they are the real experts. By working with others who have the same problems, they can try out different solutions and find the one that works best.

The real power of the sharing economy comes from two phenomena: when anyone (and everyone) can participate, chances are that enough of the right people will; and many small contributions can make a big difference. In companies, only a few people – the employees – work together. Companies that have smarter employees than other companies typically do better. However, there are many people outside of the company that might have good ideas, or one good idea, and there is no mechanism to incorporate these ideas in what the company does. The sharing economy is built on the premise of many people making small contributions. Because the distribution of participants is spread out when more and more diverse people contribute, it is sometimes referred to as a long tail. This is not to say that there are not some people that do most of the work. Anyone who has ever cleaned up after a dinner party will know that some do more than others, and it’s no different in open projects.

In the sharing economy, participants deeply engage with the projects they work on, and develop strong trust relationships with each other, even if they never meet in person. This kind of engagement is special and something that traditional companies are trying very hard, and mostly failing, to create. In the sharing economy it comes naturally. People participate not because they expect to be paid (although many get paid), but because they believe it is important as it helps them solve their problems or simply have fun. There are many different reasons to care and money is usually not the best one – not just in personal relationships.

Is the sharing economy here to stay? Chances are yes, because once processes have been pried open, they are very difficult to close again. Once we have access to more information about our politicians, we are not likely to give that up again. People want to design their lives and open processes let us get more involved than closed ones. Once we realise that participating in the sharing economy is fun and efficient, why would we go back to a closed model?

However, not everyone thinks this is so great. Companies and organisations that rely on the control of information are trying to implement stronger legal regulations and technological measures that prevent sharing. Tension between our new social norms and these legal and technical restrictions is mounting. The sharing economy holds great promise for culture, knowledge and business, but it needs information and ideas to flow freely.