First Published in

While the sustainable development issue remains the subject of intelligent discussion, debate and research, it is not these things that make it meaningful. Rather, it is images. Our understanding of those two big words, "sustainable" and "development", is largely defined by a vast personal library of images particular to each of us. Filed away in our minds, these images describe all that we intuitively know as being related to the sustainable development debate.

At the moment, I personally can't get a particular image out of my head. It is a fictional image of truckloads of tomatoes being deliberately wasted in order to protect food prices in the USA. I have never actually seen this image. It merely exists in my mind, prompted by an email from Josh On, a previous Design Indaba speaker. It is informed by pictures I have actually seen, photographs of farmers 'working' to earn state funding by destroying their crop surpluses.

Another image comes to mind. Lake Baikal is the oldest (25 million years) and deepest (1 637 m) lake in the world. It is also a place I have never visited - and yet its existence resonates in my mind. I recently read In Siberia, a magnificent book by Colin Thubron. In his book, Thubron touches on some of the growing concerns about pollution feeding into Lake Baikal, a lake that contains almost one quarter of the world's fresh water.

As with the tomatoes, my image of Lake Baikal exists only in my mind. It is uniquely of my own making, and is comprised of an amalgam of other photographs. It takes the form of an intriguing lenticular image pattern, quite similar to one of those two-way viewing experiences that sometimes enrich the gifts found in breakfast-cereal packaging. In my mind's eye, I can visualise the fragile, albeit imaginary, purity of Lake Baikal, this image merging with that of beached ships in the Caspian Sea, a place horrifically affected by changes in water flow and pollution.

I could go on here, the vast file of imaginary images stored in my head as endless as my curiosity for rifling through them. In choosing to reveal these two examples, I have tried to point out how influential and infinite the images are that prompt our enthusiasm for any given subject. Asked particularly to consider what role image-makers have in relation to the sustainable development debate, I would argue that they are all-pervasive. Professional photographers, including the image-makers that exist inside of us all, are endlessly at work creating an illusion of the concept known as sustainable development.

Let me clarify this by asking you to consider the following. If you had never personally experienced a dramatic example of environmental apocalypse, never even encountered an image of it, would you be all that concerned about the issue of sustainable development? I argue not. We only care because our intellectual engagement of the subject is backed up by a searing set of images that argue its case emotively.

We live in a rationalist age where everything needs its credibility proven, everything needs to be made real. Very often it is images that achieve this, quite irrespective of whether they are 'real' or imaginary images. The irony is that 'real' images - those artefacts that actually document the external world - can be so much more misleading than the ones we dream in our mind. At least we know the facts and fancies that have fuelled our imaginary images. Not so, however, with an ostensibly real image; it is so much more fraught with problems.

If you weren't there when an image was taken, you really cannot know what truths lie beyond the camera's frame, or how these other truths would affect how you interpret the truth captured in the lens. And even if you were there, it is no less problematic. What if you had arrived earlier, or later? What if you had simply turned around, or dared to walk a little way further to take a photograph? Is there not a likelihood that you might have seen and captured some other information, information that like so much else in this world is conflicting and contradictory?

Images and image-makers bear a huge responsibility in fostering and developing our notion of what sustainable development means. They can either underpin, or undermine what we think we know. This is the mercurial nature of documentary photography, and defines its importance in giving credibility to 'what we know'.

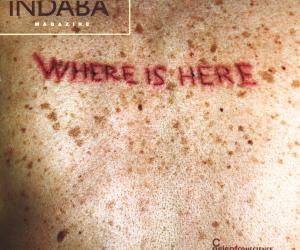

To illustrate my point, pause for a moment on the accompanying image. I could start out by telling you that it is documentary photograph, or suggest to you that it was art directed. I could state that it is quite recent, or suggest to you that it was taken some years ago. I could digress, talk about filters and film, even linger on the technical aspects that may have subtly altered the illusion we see.

As it happens, the photograph is a documentary picture of a Naga Sadhu holy man, a naked ascetic representing one of Hinduism's most revered holy sects. The photograph was taken by Art Wolfe, an individual whom I have previously written about in this publication. Art is a photographer with impeccable credentials and his images bear testimony to a responsible and concerned individual. I was with Art when he took this particular photograph. Of course, I may have given him some art direction in the sense of 'going in close', and we may have chosen this particular man because his face paint was done with the most conviction. But other than these concerns, this is a 'real' image, if you care to believe me.

I selected this image of a Naga Sadhu holy man because his image speaks of a world threatened by industrialisation and globalisation, a world where the most extreme practices at the heart of the world's oldest religions are increasingly out of step with other facets of Indian culture. His image might hardly speak the conventional concerns underpinning the sustainable development debate, but then it is as important to understand the intangible spirit that drives our collective concern for a sustainable future. The debate is not simply about economics.

Feeding that spirit is perhaps the most valuable thing the image-maker can do. Perhaps all else is illusion.

Lewis Blackwell is senior vice-president of Getty Images. He is the author of several leading books on design and communication, including the End of Print and Edward Fella: Letters on America. His most recent publication, edited with Chris Ashworth, is Soon: the future culture of brands. For more images by Art Wolfe go to gettyimages.com