First Published in

It may not be wise to judge a book by its cover, but we do. And if you’re browsing in one of South Africa’s bigger books stores, which stocks at least 30 000 individual titles, all roughly the same size and shape, a book’s cover can seem, well, all-important.

Imagine a packed stadium full of teenage girls, each trying to get the attention of Robbie Williams. The competition is not unlike that.

Author cachet and marketing are huge factors, of course. They can, in fact, mean that book buyers don’t care what a cover looks like, as long as they’ve seen the book clutched and held aloft in Oprah’s manicured hand. But for your average reader with a gift voucher, scanning the shelves in idle curiosity, The Cover is king (closely followed by that royal jester-cum-spin doctor, The Blurb).

No wonder a huge amount of effort goes into creating and selecting a cover for a book. Yet until quite recently you wouldn’t have said this was the case in South Africa. People would say that a book ‘looked local’ (polite-speak for ‘ugly’).

In the past few years, fierce competition – from UK publishers, DStv, magazines, new local imprints – has had South African trade publishers paying more attention to their books’ packaging.

Consumers are demanding beautiful products, be they in the form of book covers, shop window displays or television title sequences. Visual engagement matters like never before.

Internationally, there are publishing houses that have built their brand reputation on great cover design, Penguin being one of them. Designers like Chip Kidd, Jon Gray (more commonly known as ‘gray318’), Kai and Sunny are renowned and revered for their book covers.

In South Africa, the trend is catching on: imprints such as Double Storey and Jacana consistently publish interesting covers and designers such as Toby Newsome, Dale Halvorsen, Richard Hart of Disturbance Design and Michiel Botha of Flame Design are becoming known for producing them.

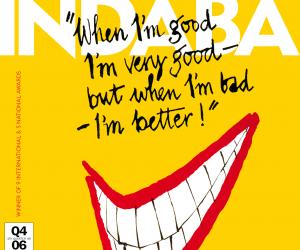

Publishers are not only more open to encouraging the art of book cover design, but are also thinking differently, and cleverly, about how they use covers to sell their books. As Michiel Botha says, “Whether you like the spirit of the new Two Dogs imprint books or not, their cheekily styled quirky covers are attractive.”

Two Dogs is the new Struik imprint for men, and they have created a standard template for all their book covers, which mimics the feel of magazine features, while also strongly reinforcing the Two Dogs brand by treating the logo as a kind of masthead.

“The best book jacket design, like any other design, should be a surprise and a brush with the unfamiliar,” says Richard Hart. “This isn’t always possible and sometimes publishers ask designers to follow a formula, anticipating (perhaps correctly?) that readers who are used to having certain types of literature packaged in certain ways will respond to a product packaged in the same way.”

Toby Newsome confirms this, but suggests it’s not necessarily a bad thing: “There are formulas, especially in educational and academic covers, where there is a lot more concern about legibility and misinterpretation,” he points out. “There are also classic design approaches which can be revisited time and again.”

Designer Sean Robertson believes that most staid formulas are not consumer driven: “I think that the more conservative publishers stick to what they think are winning formulas, which might make people think that there are set formulas in place. A cover is supposed to have impact and make the buyer at least pick the book up out of interest. But does a cover need to be in your face in order to make an impact? I don’t think so.”

Michiel Botha proposes that there should not be formulas, as such, but a visual language that could be subverted to enrich a design or increase its impact.

The idea that book cover design has a visual language that needs to be acknowledged and then tweaked for on-shelf visibility has seen interesting new cover approaches in genres that have traditionally had formulaic covers (generally, literary fiction titles are where publishers allow themselves to get ‘arty’).

Jacana is currently in the process of re-jacketing its Sappi Tree Spotting series. The originals showed the usual ‘tree-dissected’ approach of most field guides. The redesign (by Georgina MacRobert of Hothouse Design) combines the formality of traditional botanical illustration suitable for a guide with an unconventional tight crop that evokes the sensual beauty of the subject being examined.

There may have been some fear of losing the appeal to the ‘common denominator’ in this approach, but in a world inundated with information there’s the real potential for success for publishers who have the conviction to aim straight for the intended consumer.

For example, the image selection of the Struik cooking title Season to Taste avoids typical mass market ‘food porn’ or chef deification á la Jamie Oliver and appeals directly to the precision and aesthetic clarity of the professional chef, the main target market of this book.

When considering the character of a particular book, it may be important to the integrity of the work that a publisher and designer subvert the expected.

The cover of the autobiography Acid Alex by Al Lovejoy, illustrated by Anton Kannemeyer and published by Zebra Press, both eschews and embraces the ‘moody, posed author photo’ convention used for memoirs and uses the right illustrator to capture the author’s personality in a memorable way.

For publishers, how much of a cover design is a physical manifestation of the author’s vision and how much of it is product packaging is a sliding scale that depends on the book.

“In an ideal world,” says Richard Hart, “the designer would always read the manuscript (the best covers I’ve done have always been for books that I’ve read before designing), and make a considered, thought-provoking cover that complements, even extends, the thrust of the work. But time and money don’t always allow for this and often covers are simply thrown together or worse: a solution is dictated based on notions of market tastes.”

Authors can give designers the inspiration they need to ‘solve’ a cover, but they can’t always drive the process.

“Authors often have very clear ideas about what they imagine the cover should look like,” says Newsome. “This is always useful, but I don’t let it stop me from looking in even completely different directions.”

Sean Robertson explains, “I don’t think that a designer should only try and make the author’s vision a reality and ignore what works on a bookshelf. This is where the publisher steps in.”

This is probably one of the most inspiring, yet frustrating, elements of book cover design for designers: the number of cooks stirring the broth.

Andy Jamieson and Greg Lomas of Green Tea Bag Design describe the three spheres of influence in the cover design process: The Designer, The Author and The Publisher (who usually also embodies the opinions of the company’s sales, marketing and production staff). The more common ground shared, the smoother and quicker the process will be.

The production process puts more pressure on designers. Print runs in South Africa are small – usually about 3 000 copies for a first (sometimes entire) run – which means no economy of scale. Design budgets are tight. Paper is expensive and the range is meagre. Special inks and other processes are very expensive and local repro houses have limited experience with them. While some designers and publishers claim that if you can’t pull off a decent cover design in four colours then it’s not strong enough, others would like the money and opportunity to have a bit more fun.

A cover like Michele Staples’s At Her Feet (by Nadia Davids, Oshun Books) was lifted from ordinariness by a veil-like UV spot, a clever solution for a play about Muslim women that had to have a patterned cover (representative art is not permitted in Islam). Production extras must make publishing and design sense; as Sean says, “Sometimes too many finishes can ruin a book cover just as quickly as too few can.”

When budget does allow it, designers can enjoy pushing the boundaries of what the book format allows.

Toby Newsome’s end papers for the anthology Nice Times! (Double Storey) enrich a book that celebrates joyful indulgence.

The full, bright flaps of Glass Jars Among Trees (Jacana, designed by Roger Jardine of Disturbance Design) mirror the colourful surprises of the book’s content.

Cover design can even extend to the title page. In fact, a well co-ordinated book design should see the cover pulled through the whole book.

“It’s very easy to see when a cover is freelanced out and the typesetter or book designer does not communicate with the cover designer,” says Robertson. “Fonts differ, design styles fight and it just looks like a forced relationship between the inside and its jacket. Obviously budgets can determine what the inside of a book looks like (cash for illustrations, photos and so on) but this does not excuse poor design and weak typography inside a book.”

Lauren Rycroft of Flame Design enthuses: “There is enormous potential for book design and typesetting in this country. People are becoming more visually literate and information is also demanding to be more visually accessible. It’s a great opportunity for designers.”

For all its challenges, book cover design is still highly conceptual work that offers great rewards for designers. “No-one in South Africa is going to make a living doing book covers exclusively,” Richard admits. “But they do offer unique design opportunities… and it feels so much better dressing a work of literature and contributing something of cultural value, than devoting time and talent to an anonymous corporate bottom line.” Michiel says simply, “It makes my heart beat.”

The question nervous publishers are still asking themselves is: “Is the South African book-buying public ready for interesting, subtle cover design?” “I don’t know,” says Richard, “but I think there’s a growing awareness and appreciation of good work. I’m often complimented on my good book designs, never on my crap ones, so at least there’s an appreciation of the difference!” Eventually, traditional book publishers will have no choice but to respond to this growing awareness. As information goes digital and people go visual, the stimulating physicality of a well-designed book is the ultimate USP.

Interview

Are South African book cover designers responding to trends in other areas of South African design (visual, fashion, product or other)? Are they using these trends to enforce a ‘local’ aesthetic?

Toby Newsome: I think there is a response, yes. There’s a lot more illustration being used, as well as collage and references to old SA packaging, scrollwork and so on. As far as ‘local aesthetic’ is concerned, I hope it’s something that just happens and is not enforced. It’s only going to happen thanks to individuals who are passionate about what they’re doing and who have an awareness of other artistic media around them.

Michiel Botha: I don’t think designers are consciously responding, but they’re certainly drawing from local trends, whether these are purely local or influenced by international trends.

Is a book a product, an artistic endeavour, or both? Should the designer aim to complement the author’s vision or simply package it for the reader?

Newsome: It can definitely be both, but it is paramount to complement the text or key ideas espoused. Ideally it’ll be as enticing to the author as to the reader.

Botha: Both. Very importantly, it’s a form a communication. Designing for fiction is different to designing for an academic text – the genre of the manuscript determines the design to an extent. But it’s lovely to mess with this distinction and generate surprise through design.

What methods do you use to produce your covers? Which do you think are most effective?

Newsome: I love working with illustration, and hand-made design elements. I love playfulness in covers – of course, not all books lend themselves to this.

Botha: Get a feeling and understanding of the manuscript. Determine who you are speaking to and do research. Be familiar with the visual languages of different genres.