First Published in

A quick gloss through the general archives throws up names such as James Montgomery Flagg, famous for his 1917 conscription poster for the US army, or, on the other end of the spectrum, Seymour Chwast, whose 1967 antiwar posters can be seen in New York's Museum of Modern Art. But what happens if you tighten the focus a little by concentrating on South African posters, especially that great body of work produced during the 1980s?

It is said that the real era of South African posters began in the 1980s, a fact largely attributed to the formation of the Screen Printing Project (STP) in Johannesburg and the Community Arts Project (CAP) media project in Cape Town. Thus despite some interesting anti-fascist pro-Allied posters dating back to the 1940s, the most interesting political posters to concern themselves with the theme of war and militarism date back to the 1980s. The history of these posters is particularly tied up with that of the End Conscription Campaign (ECC), a grassroots organisation that used design activism to challenge the mandatory conscription of white South African males.

The story of the ECC is a short one, but nonetheless offers a meaningful account that is intimately a part of the larger narrative of South Africa's struggle for freedom. Formed in August 1984 by a small number of white students at the University of Cape Town, the organisation played a key role in late 1980s grassroots politics, tirelessly campaigning against white male conscription. But there was more at stake than just conscription; the ECC openly questioned the increasing militarisation of South African civil society. Such a policy, of course, garnered the group enemies.

Former Defence Minister Magnus Malan, in a rather conceited outburst, branded the organisation "anti-South African", while Gavin Evans, an ECC activist and Weekly Mail reporter, narrowly escaped being murdered when apartheid agents sent to despatch him went to the wrong address. (The plan had been to stab him and make it appear the work of burglars.) The ECC's political career, if one could call it that, only spanned a meagre four years in total. The national State of Emergency of June 1986 effectively heralded the organisation's demise, as calls for an end to conscription were made illegal. Undeterred, the ECC soldiered on, the government finally resorting to banning the organisation from "continuing any activities or acts", in the spring of 1988.

Why so much fuss over an organisation comprising 40 offices (mostly campus branches at that), an organisation seemingly concerned with one detailed minutiae of the apartheid monolith: ending the mandatory conscription of white male South Africans? The answer spans more than the short period of the ECC's existence, and starts in 1912. The Union Defence Force was South Africa's first national military force, established some two years after the formation of the Union of South Africa. Early on in its history the South African military played a key role in "policing" civilians, troops used to suppress strikes by white mine workers in 1914 and 1922.

It was not until the 1960s that expenditure on defence started to become a priority for the state. A United Nations sanctioned arms embargo, as well as the concurrent development of Armaments Development Corporation (ARMSCOR) were formative in shaping a burgeoning military culture within the pariah state. By the mid-1970s, South Africa had built up a powerful and significant arms industry. In 1979 over 14% of state expenditure was allocated to defence, the newly empowered military flexing its muscle all over the subcontinent.

While much of Africa was coming to terms with the winds of change heralded by decolonisation, South Africa intensified its own form of military (and economic) destabilisation of the subcontinent. The defence force were involved in invasions and "hot pursuit" operations into Angola, pre-emptive strikes against the South West African People's Organisation (SWAPO) in Namibia and Angola, actions against the African National Congress (ANC) in exile in countries such as Mozambique, Swaziland and Lesotho, and military support for rebel anti-Marxist groups such as RENAMO and UNITA.

All this activity was paired with increased spending on the military. In 1982-83, for instance, defence expenditure had risen to almost R3 billion, and by the mid-1980s almost 20% of the government's total annual budget was devoted to defence. Not that money was the only fuel needed to bolster this system; a constant supply of ideologically sound young recruits was equally essential.

"Conscription was the most intimate connection I had to the struggle being fought on so many fronts in my country," recalls ECC activist Kathryn Mathers. If the war in the townships was an abstract to many white South Africans, the militarisation of everyday life wasn't.

Retail stores displayed 3D posters of anti-personnel mines, triangular roadside signage indicated where it was okay to pick up young recruits on leave, and white schools enforced a weekly regime of cadets, or youth preparedness programmes. Alongside the promotion of war toys and games, there was a compulsory system of registration of 16-year-old white boys for conscription and the progressive extension of compulsory military service for white male youths to two years (in 1985) plus annual camps.War was omnipresent - quite literally.

From 1981 to 1988 the SADF was also more or less permanently inside the provinces of Cunene and Cuando Cubango in Angola. On the home front, in 1985 alone, some 35,500 troops were used in the townships to evict rent defaulters, occupy classrooms, identify the injured seeking treatment in health clinics, and break strikes - a key campaigning point for the ECC. The creeping military empire sponsored by the government did not come cheaply. In 1986, at the height of South Africa's counter-insurgency war, 453 SADF members committed, or attempted to commit, suicide. As Kathryn Mathers states, conscription depended on misplaced patriotism and relative poverty. For many white youths, the border also became an ephemeral place, a place "more ideological than geographic."

This intrusion, of the mechanics of the apartheid state on white privilege, proved fertile territory for the ECC. As Judge Edwin Cameron, a tireless campaigner for the ECC, recently pointed out in a Mail&Guardian interview, the ECC's success largely derived from the organisation's pinpoint focus. Rather than attempting to confront a broad range of issues, the ambit of their assault was specific: conscription, troops in the township, the fractured psychology wrought by a faltering system.

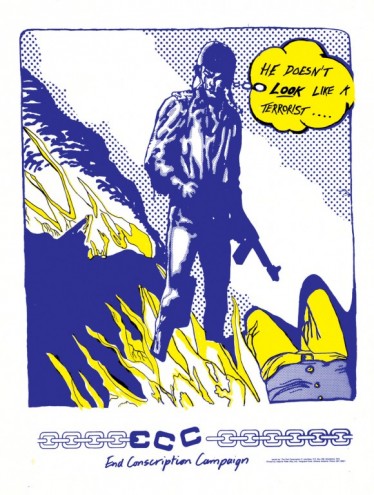

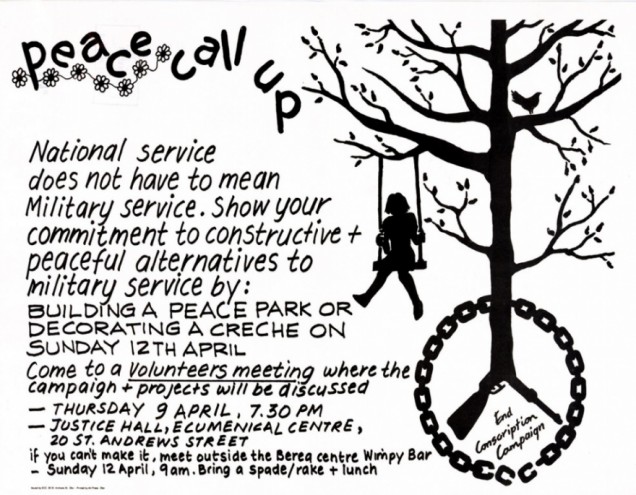

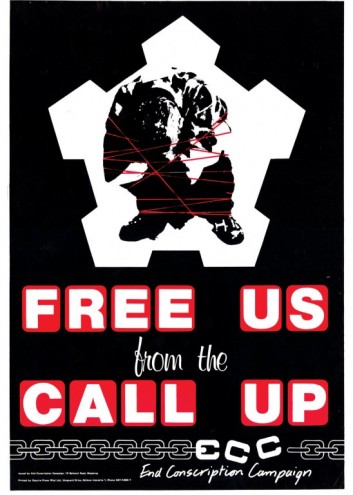

Not that the various remnants and artefacts of the ECC's enthused campaigning are by any means the apotheosis of the graphic form they exploited: the political poster. Like many artefacts of the South African anti-apartheid movement, the visual style of the ECC was visually naïve, stylistically raw, in short a mess. Which isn't to say that the output of the antiapartheid movement (or the ECC) isn't interesting.

Forced to operate on modest budgets, sometimes in clandestine cells subject to police harassment and sabotage, the rough-hewn style of the anti-apartheid poster is as much a testament to a haphazard process that birthed every poster, as it is a celebration of a tireless spirit of activism. The jarring colour schemes, erratic selection of typefaces, some of which were even hand-lettered, even the plagiarised antiwar motifs used by largely volunteer designers, all attest to a visual style that was shaped from the ground up. This is quite significant given the current propensity for advertising focus groups to dictate the content of anti-Aids posters.

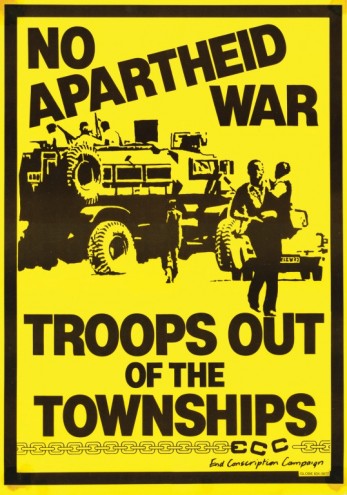

Some of the group's posters were however quite sophisticated. A good example is the poster calling for troops to remove themselves from the townships, an image also used for the cover of the Forces Favourites album, a musical compilation sponsored by the ECC.

Imprinted on the sleeve is one of the ECC's most striking graphic images, the outline of a Casspir armoured vehicle set against a yellow backdrop, the unmistakable chain-link logo running across the bottom of the image. The whole concept for the album is striking example of the Situationist trick of detournement, or the theft of aesthetic artefacts from their contexts and their diversion into contexts of one's own device. In this case the album's title was a loaded reference to a popular nationalist radio show, that every Sunday broadcast letters and dedications to conscripts on the border. It predated Laugh It Off's corporate hoax T-shirts by almost two decades.

This pop-political approach proved quite successful in attracting members to the ECC, people from disparate ideologies and backgrounds. As with any political organisation, the broad framework of 'the cause' had to resist its own internal contradictions. Ivan Tomms, for instance, a gay doctor in the township of Crossroads, was one of the ECC's most prominent activists. He had conducted a 21-day fast as part of the ECC's 'Troops Out of the Townships' campaign, and was later jailed for refusing to attend an army camp. As part of his defence, Tomms had discussed raising his homosexuality as a primary reason for justifying his conscientious objection to the army.

Daniel Conway, an academic researcher at WITS, recently revealed that fellow members of ECC prevented Tomms from incorporating his sexual identity into his objection. "Gay activists in the ECC were amongst the most opposed to Tomms using his sexuality as a basis for his objection," says Conway. "The ECC's reasoning was undoubtedly influenced by the states conflation between their individual political stances and their personal sexual identities. "Not known to overlook the power of parody (fascist detournement?), state-sponsored groups were known to promote slogans such as, 'ECC gets you from behind' and 'Every Cowards Choice'.

That there is a darker subtext at play is borne out by recent findings published by Noel Stott, a researcher at the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation. In an extensive review of the South African military he refers to findings implicating the SADF in a secret project to "cure" homosexuals, by means of sex-change operations, medical torture and chemical castration. Psychiatrists, with the assistance of army chaplains, identified suspected homosexuals amongst new conscripts. Those who were identified were sent to Voortrekkerhoogte military hospital in Pretoria for screening and "rehabilitation". Those who could not be "cured" by drugs and psychiatry were given sex-changes or chemically castrated. One Mail & Guardian report claim that about 50 sex-change operations were performed annually between 1971 and 1989.

Not that the ECC posters always confronted these darker secrets. But ECC's activism did touch on issues far deeper than simply the erosion of white privilege by the apartheid state. Unbanned in 1990, alongside the African National Congress and a host of other liberation movements, the raison d'etre for the ECC's existence dissolved on the eve of 1994's first democratic general election. The SADF was replaced by the South African National Defence Force, a new military structure that integrated the non-statutory forces of MK and APLA with the SADF and homeland forces. Mandatory conscription was done away with.

While the South African military is heralded as one of the most successful state sectors to deal with transformation the presence of South African soldiers in Burundi and the DRC, as well as the furore surrounding the recent armsprocurement deal, suggests that the semantics of power, particularly military power, are still a constant of South African life. Quite possibly it will take a new batch of graphic activists to craft a visual language to challenge its threats.