First Published in

Historically, South Africans have been starved of design - to the detriment of our culture. Slowly but surely, however, the public, industry and government are starting to grasp the fact that design is not some trivial activity that flirts around the fringes of our economy. On the contrary, design forms the core of a knowledge economy and is a powerful and critical function for driving economic growth.

But the question begs: why have South Africans taken so long to embrace and harness the natural human trait of creativity? Some will argue that South Africans are indeed creative and I would not dispute this. The question revolves more around the fact that we are not creatively competitive in the international arena.

What I am saying is that "South Africa does not have a design culture" on a broader national level. I can almost anticipate a barrage of criticism for making such a statement.

"What about our world-class advertising industry, our flourishing interior designers, fashion designers, or even the Kreepy-Krauly?" you may argue. Indeed, these are examples and proof that we have great talent in our country; but it does not mean that we have a design culture.

So what do I mean by a design culture?

Take industrial design, for example, which is arguably the most marginalised sector, both historically and currently, in South African design. Yet industrial design should form the vanguard of the manufacturing sector and competitive advantage in our country.

Industrial design as a profession was born from the industrial revolution when machines, manufacturing and technology combined to mass-produce the products and systems that we use in our everyday lives. The countries that led this revolution in the late 1800s were Great Britain, Germany, the United States of America, Europe and, last but not least, the Asian Tigers of the East - Japan, Taiwan, Singapore and, during the last decade, China and India.

But not South Africa.

If we take a brief look at what international management, economic and design gurus such as Richard Florida, Tom Peters and Francis Fukuyama are saying about contemporary design, then some interesting points can be raised about the South African scenario. These include the fact that successful economies are progressing towards "advanced industrialisation" where the design process from "idea to market" is now a highly sophisticated process. The political and social structure of a country is also crucial to developing a knowledge economy - where democracy and a liberal constitution are regarded as fertile breeding ground to encourage the creative class. South Africa can truly boast of such political and social attributes. Yet it cannot boast of any advanced industrialisation.

A recent cover article of the Engineering News, October 2005, reads: "Manufacturing Wilderness - Domestic manufacturers say de-industrialisation threat is all too real". The article further explains the "lack of design and engineering skills" as one of the key reasons for this dire situation.

But why is this so? The reasons for a lack of a design culture run deep into the psyche of South African industry - and the country's political history. During Apartheid, design became yet another weapon of the regime, in that the majority of industrial design companies were military. Such military companies were supported heavily by the government's "research and development" funds. Such companies then sold their products back to government at huge profits.

In the quest to develop military products for the purpose of "defending the laager of Apartheid", international patents and designs were also ignored and disregarded at will. It was with similar contempt that the apartheid regime ignored international laws against human rights abuses. The resulting products usually consisted of ugly metal "boxes", defunct of any aesthetic value and based on a racially slanted design process, which set the primary function of the design brief that the product had to be "kaffir-proof". This term depicted the culture at the time that regarded black people as being "too stupid" to use products as they would inevitably break them. Thus a "good design" was one which a black person could not break. Ironically, much of the technology and products developed during the apartheid era were used to kill black people. Take for example the only vehicle South Africa has ever designed - the armoured Ratel, a tank-like truck, would bear troops into the townships to quell political resistance.

At the end of the Apartheid era, ex-military companies simply re-tooled and supposedly turned their technology towards "commercial" development to take advantage of South Africa's re-entry into world markets. There is of course nothing wrong with such a strategy. Except for the fact that the bastardised "military design culture" of the apartheid era was still prevalent in such companies, as was incredible ignorance as to the meaning of "industrial design" and international competitiveness.

South Africa is highly acclaimed the world over for having achieved political and social "freedom" for all her people but I argue whether we have achieved the basic creative right of "freedom to design". The problem of course lies in part with a culture of design and development that was fuelled by oppression and a verkrampt, ignorant and contemptuous disregard for the value of design.

A "culture" is about a "way of life" that is accepted, respected and valued by a certain community or country. A "design culture" would then mean that DESIGN is accepted as a valued contributor to economic growth and therefore given the respect it deserves.

A national design culture would also mean that industry, government and the people of a country demonstrate pride in the creative process because they understood the value of design. Our new democratic government seems to understand such value yet our manufacturing industry, which seems for the most part to be rooted in the past, does not.

A design culture cannot be imported. It cannot be bought. It can, however, be created. In South Africa, due to our past and current experience, it seems this will have to be created through revolt by the people for the "right to design" and the attendant economic success. A design revolution. And by good South African custom, a peaceful one, for the prosperity and benefit of the people of this country. o

About the writer

Bernard Smith's company Artec Product Design is the winner of a Technology Top 100 Company and Export Achievement award, presented by President Thabo Mbeki. Its design for one of the biggest breweries in the UK utilises bar code and infrared technology to electronically track aluminium beer kegs to prevent theft.

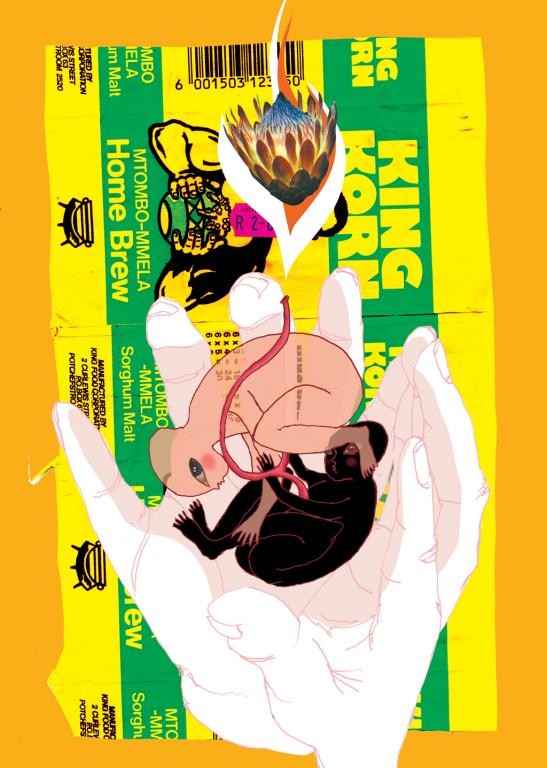

About the illustrator

Sheila Dorje created this piece in response to the article. Before starting her own company, Snoek Design, three years ago, she worked for Orange Juice Cape Town and her work appeared frequently in Garth Walker's i-Jusi magazine.