Beneath a Christoph Niemann illustration there lives an entire story, which is often discovered with a spontaneous smile. For years the German artist’s drawings have been delighting audiences on the front covers of the The New Yorker, Time and The New York Times, making him a well-known name in the industry.

Settled in Berlin, Niemann spends his days in his at-home studio where he sits drawing cartoons and creating illustrations for various publications. We pulled the busy illustrator, graphic designer and author away from his desk to discuss his current exhibition at the Bluerider ART gallery in Taiwan, what social sharing has come to mean for artists, and his insight on the very act of creating.

Would you mind telling us a little about your current exhibition, The Observer, at the Bluerider ART gallery?

It’s my first exhibition in Asia, which is very exciting. What’s new about this show is that this is the first time it’s only original drawings. Something that has happened over the last few years is that – through Instagram especially, and also Twitter and Facebook – I’ve started showing more and more original drawings, whether it’s ink or pencil. And that has created a nice relationship directly with viewers, whereas before my work has always been shown through magazines or through books. Now I feel that these personal drawings are a new way of communicating with those readers.

How would you describe the style of your illustrations?

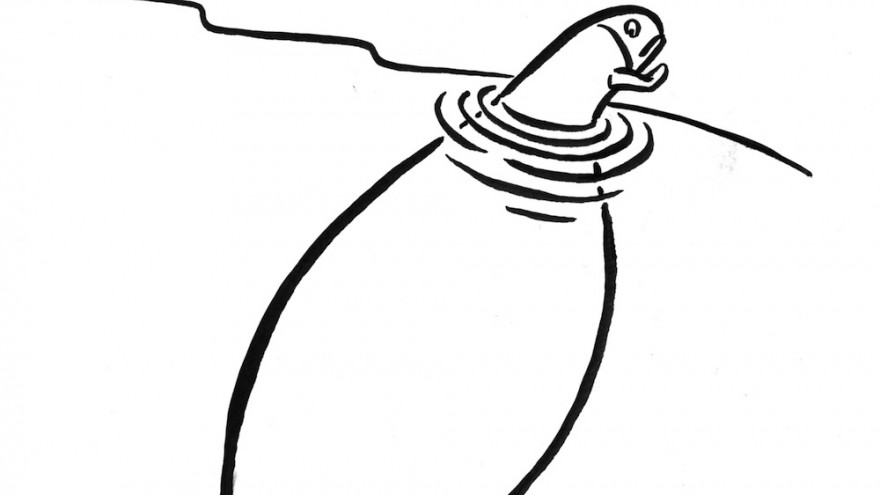

I’ve always tried to be very unpredictable stylistically. I try to do new stuff with very traditional methods. It always comes back to the question of trying to find the right amount of abstraction. For me, this is the most fascinating aspect of drawing. The idea of taking the 3D world into 2D and describing with very few lines a very complex situation or object is the greatest power of drawing.

You have a rather systemised daily routine – how do you find creativity within it?

Often it’s just a matter of sitting down and drawing. Of course it’s very difficult when you work under deadline or when you start a big project, there’s always something to do and there’s always an urgent thing to finish. I have a big demanding To Do list, which on the one hand is great because it structures your day but on the other hand, it means I have to then force myself to take an hour to draw.

Drawing is an amazing exercise in feeling and in looking.

Do you ever wake up and think, “Erg, I just really don’t feel like producing anything today”?

Frankly, no. I have days where I feel that I might not have the touch to do a drawing that has a special something but I wish a day had 72 hours because there’s always so many things I want to do. And then there are also so many different kinds of work – if I don’t feel artistically inspired, I’ll work on something that presents more of a technical problem. But I have to say that I’ve never had a day where I say, “I just don’t feel like it at all.” Maybe I should! Maybe I need to take more days off and just recalibrate.

Did you start doing children’s books after becoming a father, or were you doing them already?

I didn’t make a vow to never do children’s books but I always thought that children’s books for illustrators are a little bit too predictable – like little girls wanting to become doctors for horses. It happened pretty organically. It was a story for my oldest one, who was terrible at falling asleep. The only way I could make him to go to sleep was to bore him to sleep and ramble on for half and hour in a senseless combination of all the things he likes: helicopters, police, fireman and clouds. I mixed these words together into endless, super-boring stories until he eventually just gave in and one evening I realised this story actually made sense and that became my first children’s book.

What’s different (more liberating or more challenging) about creating for a young audience?

I don’t see that much of a difference. Obviously you use different metaphors and may not work with images or scenery that requires historic or political knowledge but ultimately I think it’s very similar. Kids are very smart and grownups are sometimes not as smart as one might think, but I don’t have a different approach.

What has your work as an illustrator taught you about yourself?

On the one hand, my work is my greatest reason for being afraid of going insane. On the other hand, I think that it’s the single thing that has kept me from going insane. But I don’t know if there’s a greater truth that I have learnt.

When you were a kid, is there anything in particular you liked to draw?

I was pretty much into the straightforward pirates, monsters, knights and weaponry business. There was nothing outrageously special that I did.

Do you ever get anxious about people’s opinions of your work before it gets published?

I think you have to make yourself independent to a degree. But I think it is extremely hard to deny that in any creative profession there is always a certain amount of vanity involved and I don’t even think it’s a bad thing. If you are a fashion designer, of course you have to dream of people on the street wearing your clothes. I’m an artist and of course I’m driven by the idea that people will look at my drawings and be excited in the same way that I look at other people’s drawings and get excited. This can also be paralysing if you just sit there, not able to draw anymore because you’re so anxious about what other people think about your work. So I think during the act of creation you can’t try to second-guess what people will think.

Would you say that you are your own toughest critic and do you think that every artist should be?

Yes and no. Every once and while you have to step outside your own persona and look at your work as an evil misanthrope to find all the mistakes, find everything that’s wrong and really ask yourself, “are you doing lame work or relying on old tricks?” I think it’s extremely important to be critical and yes, maybe be your harshest critic. But what’s as important as that is that you separate that from the creation because I think during the act of creation it will just completely paralyse you. The moment you put the pencil in your hand that’s when you have to be very benevolent with yourself, and trusting, and daring. If you are too critical there is no way you can create something exciting.

Are your private sketches and doodles just as important to you as your most successful (public) pieces?

I draw my kids very often and I have not much intention of showing these because they’re private. But the whole divide between personal and public work has completely changed and become one. There used to be a time where you’d draw for a magazine or for a book, and that was public and then you did your own things and showed them to friends, and that was private.

Now when I share something on Instagram, the audience can quickly become much bigger than a normal magazine would reach.

We have to be careful with these platforms because I still want to do quality stuff – I don’t just want to put out anything. I give the assigned work and the unassigned work the same amount of importance because the only thing that matters to me in the end is what effect the work has on the viewers.