First Published in

"The great struggle in life is not between good and evil… but the desire for certainty and the desire for freedom. Freedom and certainty cannot equally co-exist. The more you have of one, the less you have of the other." - Tim Robbins in Even Cowgirls Get the Blues.

The modern world is a place of paradox and nowhere more so than in the emerging economic nations. Money, it seems, is a key factor in the global melting pot of certainty and freedom.

Western culture has traditionally put emphasis on individual interests, while eastern culture has stressed collective interests. But now, in direct contrast to the Confucian ideal of seeking benefits for the whole, there is a growing advocacy of individualism that has resulted in huge psychological tensions and societal conflicts in many "new" economies. More money implies more choice and freedom and in all corners of the globe the individual is increasingly taking the centre-stage role.

So, the greater the personal freedom, the greater the opportunity for individuals to truly be whoever they want to be. With the advent of the Internet, "how to" and "how not to" information is readily available at our fingertips. It's possible to use web information to develop all the different aspects of our personalities - we can "learn" to be anything we want to be, whenever we want.

We can now dress up or dress down - we can choose our core motivation in accordance with circumstances, company, mood and desire. We pick and choose contradictory behaviours; we are "modal". This is undoubtedly the era of "multi-me".

Indeed, with the increased cross-pollination of Eastern and Western tastes and styles, and "modality" or contradictory behaviour an ever-real phenomenon, it is now impossible to describe a single "consumer type". The English, the Chinese, the French, etc. can no longer be boxed as one collective.

What implications does this have for design? Is it possible to represent a contradictory consumer in one package design?

Design serves as both a tool and a language to harness a brand's power and potential. It is a key medium, principally because it can reconcile contradiction by simultaneously appealing to our split personalities.

In the beauty world, for example, the "ingredients" listed on a cosmetic brand can appeal at two different levels: at a functional level ("pore cleansing") or at an emotional and pampering level ("enriching" and "illuminating"). Designing for the cosmetics industry has traditionally responded to either a key emotional benefit or a functional benefit of the product. However, in this modal society, it is increasingly important and indeed possible to appeal to a number of needs at the same time and, in effect, design for the contradictory consumer.

So are there any key starting points for designing for the contradictory consumer?

Think in evolving terms. No design should be completely static. If possible, there should be an element that is continually changing. Imagine an original design that has the capability to evolve in the user's hands like the FUSE phone that changes shape to fit the individual's hand shape and size. Rem Koolhaus's Prada Store in New York is another perfect example of a design in continual evolution or a constant state of re-incarnation. It is a store that has the capability of transforming itself into a catwalk, a theatre or a museum. If desired it has the flexibility to create a new look everyday.

Designing for the contrary consumer should, in fact, allow for their participation in the creation process. In essence no design should be 100% wholly designed by the "designer". The opportunity to personalise a product, to add a "me touch", is essentially the truest form of contradiction. A sense of mystery is also engaging to the growing number of savvy and contrary consumers. We all love to discover that extra "something" for ourselves: where there is exploration there is often delight.

Complexity will be expressed in layers. Just think of an interactive touch screen or a museum or art gallery that allows you to delve in at different levels depending on your information needs. Here, the end consumer decides for himself how much background history to buy into - power to the buyer, not the seller.

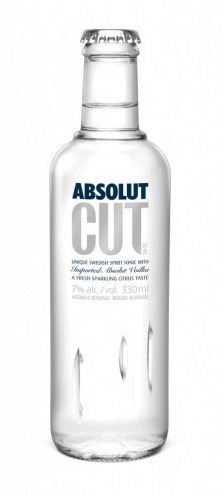

So, designing for the contrary consumer will probably have an element of surprise; an unexpected side that challenges the perceived norm and involves a change of context. The recent design of Absolut Vanilia demonstrated again how an ordinary, expected flavour could be transformed into a success story if interpreted in a distinctive way, reflective of the parent brand. The graphics were executed on a sensual matt bottle which re-introduced some of the mystery and luxury that vanilla once enjoyed and also evoked a globally understood sense of purity and premiumness; a case of consistency with personality.

Of course, design that imbues a sense of contradiction should never undervalue the power of humour. The clever use of wit can add a down-to-earth or human voice to a largely functional product and again provides a "cross-stitching" of the emotional with the functional. The US hair and beauty brand Not Soap, Just Radio and the UK Smoothies range are all perfect examples of brands that, in these uncertain and fearful times, recognise the value in poking fun at their own selves. Indeed copy has come to the forefront as a product driver. For example, Philosophy promotes back of pack information on the front of its products and uses creative and witty copy to convey product benefit. The challenge in a machine age is to add a human dimension to mass production.

The de-styled style is en vogue. Design will be stripped back to its most simple and natural form - less is more so to speak. Again, a sense of contradiction is added through a twist of context in the smallest detail or by allowing the end consumers to add their own personal touch to create a final "me" layer.

Simple, clean design does not, however, imply "average" design. The world over, now equates average with blandness. The middle ground is losing out to the extremes of high and low. Increasingly, we are looking for super-luxury or a super-deal - either way we are attracted by a risk factor, albeit perceived risk. For the contradictory consumer, it is all about perception.

Of course, a brand in its true essence is a personality, so it's important that it should have some REAL (contradictory and multi-faceted) personality. Italian brand Diesel is a great example of a brand that continues to show different aspects of its personality according to the zeitgeist at the time. Diesel design and marketing communications rely on the same underlying message but with an ever-changing and time-specific tone - contradiction implies speed. Similarly, Europe's biggest fashion-store, TopShop, themes its clothing perfectly for that exact "moment in time". Style turnaround is constant. Although designing and selling clothes might be their primary business, their secret success code is in the art of knowing what next, correctly gauging the "bubbling" undertones.

So, regardless of the choice of colour, material or copy used, designing for the contradictory consumer involves an understanding of the consumer mindset. Death to clichés and stereotypes, nothing is sacred now. Each of us, the world over, will cherrypick the best of the past while increasingly choosing to go our own way.

Going your own way involves a logical point of balance between the contradictory compass points of certainty and freedom. So, designing for the contradictory consumer will be a case-by-case scenario, where the brand in question will determine the logical point of balance between certainty and freedom, emotion and function, to transfer knowledge and desire. The challenge for all countries will be to recognise the changing personalities of people and to mirror such personalities in design.

"The great struggle in life is not between good and evil… but the desire for certainty and the desire for freedom. Freedom and certainty cannot equally co-exist. The more you have of one, the less you have of the other." - Tim Robbins in Even Cowgirls Get the Blues.

The modern world is a place of paradox and nowhere more so than in the emerging economic nations. Money, it seems, is a key factor in the global melting pot of certainty and freedom.

Western culture has traditionally put emphasis on individual interests, while eastern culture has stressed collective interests. But now, in direct contrast to the Confucian ideal of seeking benefits for the whole, there is a growing advocacy of individualism that has resulted in huge psychological tensions and societal conflicts in many "new" economies. More money implies more choice and freedom and in all corners of the globe the individual is increasingly taking the centre-stage role.

So, the greater the personal freedom, the greater the opportunity for individuals to truly be whoever they want to be. With the advent of the Internet, "how to" and "how not to" information is readily available at our fingertips. It's possible to use web information to develop all the different aspects of our personalities - we can "learn" to be anything we want to be, whenever we want.

We can now dress up or dress down - we can choose our core motivation in accordance with circumstances, company, mood and desire. We pick and choose contradictory behaviours; we are "modal". This is undoubtedly the era of "multi-me".

Indeed, with the increased cross-pollination of Eastern and Western tastes and styles, and "modality" or contradictory behaviour an ever-real phenomenon, it is now impossible to describe a single "consumer type". The English, the Chinese, the French, etc. can no longer be boxed as one collective.

What implications does this have for design? Is it possible to represent a contradictory consumer in one package design?

Design serves as both a tool and a language to harness a brand's power and potential. It is a key medium, principally because it can reconcile contradiction by simultaneously appealing to our split personalities.

In the beauty world, for example, the "ingredients" listed on a cosmetic brand can appeal at two different levels: at a functional level ("pore cleansing") or at an emotional and pampering level ("enriching" and "illuminating"). Designing for the cosmetics industry has traditionally responded to either a key emotional benefit or a functional benefit of the product. However, in this modal society, it is increasingly important and indeed possible to appeal to a number of needs at the same time and, in effect, design for the contradictory consumer.

So are there any key starting points for designing for the contradictory consumer?

Think in evolving terms. No design should be completely static. If possible, there should be an element that is continually changing. Imagine an original design that has the capability to evolve in the user's hands like the FUSE phone that changes shape to fit the individual's hand shape and size. Rem Koolhaus's Prada Store in New York is another perfect example of a design in continual evolution or a constant state of re-incarnation. It is a store that has the capability of transforming itself into a catwalk, a theatre or a museum. If desired it has the flexibility to create a new look everyday.

Designing for the contrary consumer should, in fact, allow for their participation in the creation process. In essence no design should be 100% wholly designed by the "designer". The opportunity to personalise a product, to add a "me touch", is essentially the truest form of contradiction. A sense of mystery is also engaging to the growing number of savvy and contrary consumers. We all love to discover that extra "something" for ourselves: where there is exploration there is often delight.

Complexity will be expressed in layers. Just think of an interactive touch screen or a museum or art gallery that allows you to delve in at different levels depending on your information needs. Here, the end consumer decides for himself how much background history to buy into - power to the buyer, not the seller.

So, designing for the contrary consumer will probably have an element of surprise; an unexpected side that challenges the perceived norm and involves a change of context. The recent design of Absolut Vanilia demonstrated again how an ordinary, expected flavour could be transformed into a success story if interpreted in a distinctive way, reflective of the parent brand. The graphics were executed on a sensual matt bottle which re-introduced some of the mystery and luxury that vanilla once enjoyed and also evoked a globally understood sense of purity and premiumness; a case of consistency with personality.

Of course, design that imbues a sense of contradiction should never undervalue the power of humour. The clever use of wit can add a down-to-earth or human voice to a largely functional product and again provides a "cross-stitching" of the emotional with the functional. The US hair and beauty brand Not Soap, Just Radio and the UK Smoothies range are all perfect examples of brands that, in these uncertain and fearful times, recognise the value in poking fun at their own selves. Indeed copy has come to the forefront as a product driver. For example, Philosophy promotes back of pack information on the front of its products and uses creative and witty copy to convey product benefit. The challenge in a machine age is to add a human dimension to mass production.

The de-styled style is en vogue. Design will be stripped back to its most simple and natural form - less is more so to speak. Again, a sense of contradiction is added through a twist of context in the smallest detail or by allowing the end consumers to add their own personal touch to create a final "me" layer.

Simple, clean design does not, however, imply "average" design. The world over, now equates average with blandness. The middle ground is losing out to the extremes of high and low. Increasingly, we are looking for super-luxury or a super-deal - either way we are attracted by a risk factor, albeit perceived risk. For the contradictory consumer, it is all about perception.

Of course, a brand in its true essence is a personality, so it's important that it should have some REAL (contradictory and multi-faceted) personality. Italian brand Diesel is a great example of a brand that continues to show different aspects of its personality according to the zeitgeist at the time. Diesel design and marketing communications rely on the same underlying message but with an ever-changing and time-specific tone - contradiction implies speed. Similarly, Europe's biggest fashion-store, TopShop, themes its clothing perfectly for that exact "moment in time". Style turnaround is constant. Although designing and selling clothes might be their primary business, their secret success code is in the art of knowing what next, correctly gauging the "bubbling" undertones.

So, regardless of the choice of colour, material or copy used, designing for the contradictory consumer involves an understanding of the consumer mindset. Death to clichés and stereotypes, nothing is sacred now. Each of us, the world over, will cherrypick the best of the past while increasingly choosing to go our own way.

Going your own way involves a logical point of balance between the contradictory compass points of certainty and freedom. So, designing for the contradictory consumer will be a case-by-case scenario, where the brand in question will determine the logical point of balance between certainty and freedom, emotion and function, to transfer knowledge and desire. The challenge for all countries will be to recognise the changing personalities of people and to mirror such personalities in design.