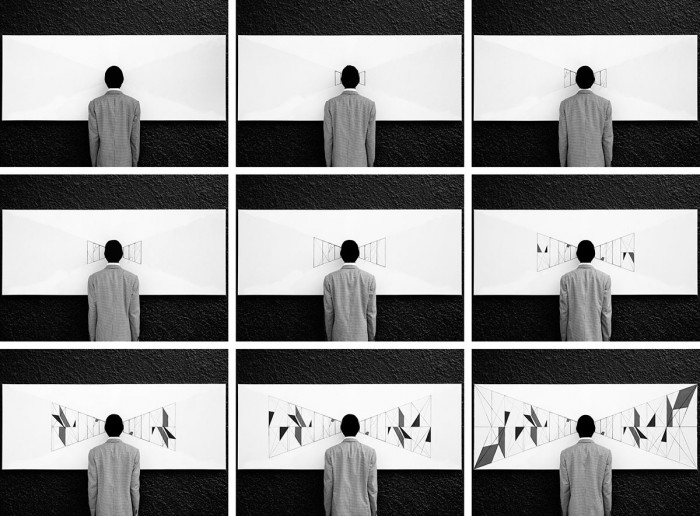

Robin Rhode is an interdisciplinary South African artist based in Germany whose work utilises a variety of visual languages to create narratives that are both personal and relatable. Pushing beyond the margins of established artistic genres, Rhode’s work merges photography, drawing, sculpture and more.

Much of his early work was dominated by performances that took place on the street and many of his performative drawings still originate on the walls of public spaces, ending up inside galleries in the form of photographs. His latest exhibition is an open-ended combination of drawings, photographs and video that at one moment feels remarkably subdued until a burst of colour evokes an unexpected playfulness.

Rhode joins the likes of Olafur Eliasson, Koen Vanmechelen and more as a speaker at the Design Indaba Conference 2017. We caught up with him at the opening of the exhibition Paths and Fields, at the Stevenson Gallery in Cape Town and got him to answer few questions.

Tell us about this exhibition...

This is my third exhibition in Cape Town at the Stevenson Gallery. This exhibition is, I would say, an exploration of drawing over a period of many years. It contains work produced from 2008 right up to 2016. So some works are very fresh while others date back almost eight years ago. But the crux of this exhibition is the exploration of drawing, of mark making, and of, I would say, a journey. Because certain works reflect experiences that I’ve had in different contexts in different places in the world, and the notion of the journey is how we make sense of those experiences.

So a lot of my work is the reflection of a lived experience and of utilising drawing as a mechanism to engage with the notions of memory and journey.

Does any of the work here engage with any particular social issues?

There are a few works here that come to mind. But as much as I am trying to address a social issue, I’m also trying to explore basic visual strategies such as form, colour, balance and perspective. There’s a work in this exhibition called ‘Lavender Hills’ – and you know, Lavender Hill is an area in Cape Town that has deep social issues. The work itself is not explicitly dealing with social issues but I’m trying to bring attention to a particular situation or space within a particular city rather than explicitly and overtly dealing with a kind of social message. So, ‘Lavender Hills’ deals with very simplistic ideas of colour and draws the viewer’s attention to the idea of a social space rather than depicting it in a literal way.

Do you think art has the power to affect any kind of social change?

I think that the intention of a lot of art is always to instigate that kind of change. But at the same time, it’s often difficult for artists to always be motivated by that. You want to maintain a kind of artistic freedom and not be governed by a particular motive.

In my work I use the element of ‘play’ a lot; so I’m playing with form, I’m playing with colour, and if the idea happens to touch on a social message then so be it.

Do you find that this notion of place has a very strong impact on your work?

Absolutely. Without a doubt, I think that Germany as a source of inspiration has had a massive influence on me and on my creativity. It’s allowed me to explore aspects of art history that I probably wouldn’t have been able to access if I lived in South Africa. So I’m also exposed in Germany... I’m exposed to new trends in the art world, I’m exposed to new forms of installation, and I’m exposed to great German artists. So I think it's really helpful for one to operate outside of one's comfort zone and I think that Germany, as hard as it can be from a personal perspective and being away from friends and family, it allows you as an artist to dig deeper and to find new points of inspiration. It also allows you to see yourself on par with your international colleagues. In South Africa, we are so geographically peripheral. Sometimes it’s easy to lose touch, and we struggle to see ourselves on par with the rest of the world. So having a distance from South Africa also allows me to also have a wider perspective of my work in the context of the global situation.

How did your journey as an artist begin?

I was obsessive about drawing as a child. I was always colouring in books – now I colour in walls! So nothing has really changed since my childhood. It’s just that my colouring-in templates have become larger and more complex. My obsession with drawing and with my imagination left my parents no choice but to enrol me in art school. It hasn’t been easy. I’ve had various phases of difficulty – whether it’s acknowledgement from my professors or lecturers or having to deal with the freedom of being in a university environment where you have the license to explore something like drawing for 6 hours. I mean, that was something that was unheard of in my public schooling. So there were many challenges and there are still many challenges ahead in terms of my trajectory as an artist.

Quite a lot of your work originates on the walls of city streets. Are you comfortable being labelled a ‘street artist’? Or how do you feel about that term?

I have to admit that I have adopted certain street art processes. I’ve adopted the mentality of a street artist but I’m not a street artist as such because the end result of my street intervention exists on a roll of film or in a gallery or museum. That’s my intention for my interaction with the streets – for it to exist in another context. The intention of the street artist is to allow their end result to exist on a wall within the public realm. So I see myself as more… as an artist that is engaged with the definition of what the street is and I explore that as a concept. What brought me to the street was the idea of allowing a contemporary art practice to be accessed by an unassuming public. This I felt was radical in the context of South African art. I believe in the ephemerality of the wall piece and that whatever I create has to disappear, it has to be destroyed.

What inspires you to embark upon a specific project?

You know, it’s almost as if every project or every idea becomes like a test. It becomes an endurance test to see whether I’m able to realise an idea fully. It’s a challenge, like this burning desire to see if I am able to take this simple or mundane idea and see it evolve into something that has a greater significance. You know, you can take something very rudimentary and you can allow that idea to snowball into something else. So I have this inner fuel that needs these ideas to be realised. It’s become like a quest, a personal quest to test myself and to see if I’m physically able to create the piece, to see if it has any validity to the discourses of contemporary art. So it's always a challenge and I always want to step up to that challenge as a means of testing myself and to see if the vision can actually be manifested into something creative.

So is it that challenge that keeps you motivated to keep producing work?

Yes, and to be part of a dialogue. To be an artist means that you have to exist and to exist means that we have to partake in the world and in the discussion. We have to be part of our society and contribute. So I think it's all of those factors that motivate me to create and to share that creation with the public and to get their responses.

To be an artist is a great privilege and sometimes we forget what a privilege it is to make art, but with that privilege comes a lot of responsibility so it's quite the challenge.

Do you have a favourite piece that you’ve created?

There are various pieces that really excite me in this particular show. I have an affection for different works because there’s a narrative behind some of these pieces – a personal narrative. For example, the colourful graphic scenes where I am physically painting and physically performing – when I look the work, sometimes it conjures that feeling of when I was in the midst of its creation and I can still hear the public and the community who were witness to it speak and comment. Some of these works have such an interesting backstory and they make simple pieces become more interesting.

But in terms of the potential of a work of art, I would say that my favourite is the work you encounter upon entering the gallery called ‘Paths and Fields’. This particular installation engages with the notion of the infinitive and I think this idea has very interesting meanings because it’s about the afterlife, it's about the eternal, and I see in this particular installation variable dimensions. So when a work of art is able to mold itself and act as kind of a chameleon, that I find really interesting.

What can Design Indaba audiences expect from your talk this year?

They can expect a very emotional presentation with elements of drama and history.

Again, I think my presentation will embody the idea of the journey, and I’m hoping to also include a short narrative of the history of South Africa over the last 15 years.

If you hadn’t become an artist what do you think you would have become?

A junkie.

Robin Rhode: Paths and Fields will run at the Stevenson Gallery in Woodstock, Cape Town until 4 March 2017.