First Published in

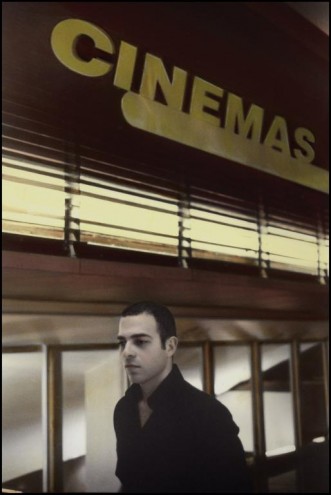

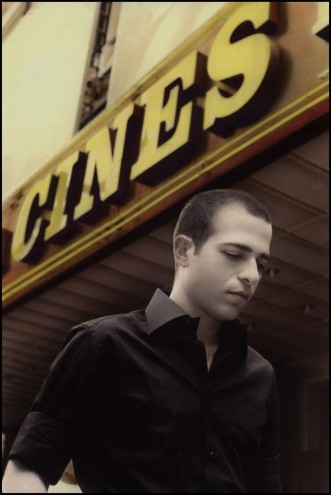

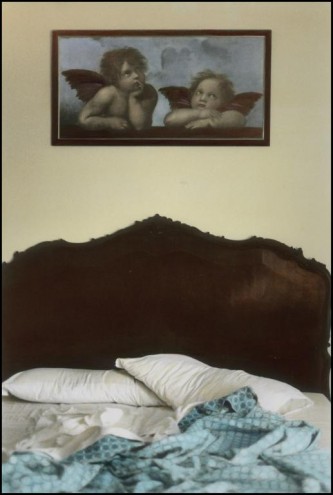

One could do worse than having one’s soul snatched by Youssef Nabil’s camera. Encased in lovingly hand-coloured silver gelatin, one would be immortalised in the style of vintage celluloid heroes, in a crematorium shared by the likes of Louise Bourgeois, David Lynch and Jean Nouvel, with a score of Egyptian film stars and a chorus of broody eyes. Such a death wish is not maudlin in Nabil’s dreamy lens. As he says, death comes everyday when we sleep.

Nabil discovered photography in the early 1990s when he and his friends would stage scenes from the golden age of Egyptian cinema. He went on to work as an assistant in prominent photographic studios in New York and Paris, before returning to Egypt in 1999. Since his debut exhibition in Cairo in 1999, Nabil has exhibited widely from London to New York. At present he lives in New York.

As Matthew Krouse puts it in the Mail&Guardian, Nabil “learned three things from his predecessors: get the famous to sit for you, take evocative self-portraits and portraits of exotic unknowns”. Design Indaba’s questions reveal a photographer enraptured with the romantic.

After starting out staging photos with your friends in Cairo, you went on to assist the likes of David LaChapelle and Mario Testino. Can you give us an account of your early life in Cairo, your discovery of photography and how you came to be the rising star you are today?

My life in Cairo was very much inspired by cinema. I started taking photographs because of my love for cinema, which is very central to Egyptians. I would ask my friends to act in scenes that I would write and photograph, always in black and white. Then I had the desire to see my work in colour, but never wanted to use colour film. So, I decided to colour them by hand using an old photography technique. I wanted to keep this old feeling in my work, to have it received as a painting as well as a photograph. Then people started hearing about my work and asked me to take more pictures. I guess one thing led to the other and I found myself having my first show at the Cairo Berlin Gallery in 1999.

With your hand-painted photographic technique, you seem to be blending the two genres of painting and photography. Can you explain this approach?

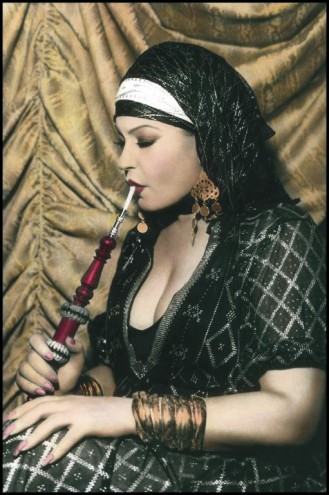

All my work is first shot on black-and-white film, then I hand-colour each of the prints in my studio, using an old photography technique. I like to mix the old and contemporary. There is something that I always loved about old techni-colour movies, hand-painted movie posters and hand-coloured studio portraits. I grew up seeing them everywhere in Cairo and wanted to keep that in my work.

Your work is heavily influenced by the golden age of Egyptian film and you say that you live your life as if in a cinema. How did you come to be so enraptured with the moving image?

I grew up watching a lot of movies – old Egyptian movies specifically. It was one of my main sources of amusement as a child. I discovered death through cinema; that actually the actors and actresses I love are dead! Being in love with all those dead beautiful people was a shock for me. I wanted to meet the ones I love before they die or before I die.

In particular you really like Federico Fellini. What do you take away from his work?

I like his way of telling a story. He’s a brilliant storyteller. His colours, characters… You can feel he was a very sensitive person. I love the fact that he was very connected artistically to his wife Giulietta Masina, who was a fantastic actress, but also his muse. I love artists like him; his work and life were one. He had a unique vision of the world and I find that very beautiful.

You have now left Egypt and live in New York, via Paris. Yet there remains a distinctly Egyptian flavour to your work. How has Egyptian culture and society permeated your work?

In my work, I speak about issues that concern me. Even if I don’t live in Egypt, I feel Egyptian, but also Mediterranean. It is always about how you feel.

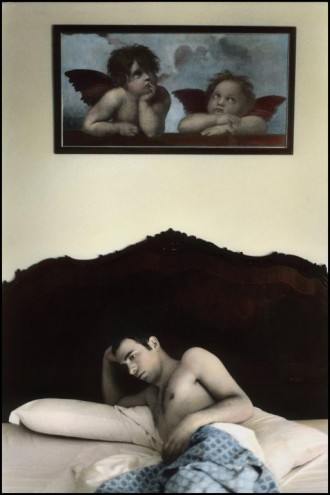

Your images slip between cinema and dream, dislocation and privacy, seeming both immediately raw and staged. What is the self that you present in your series of self-portraits?

It is part of me, maybe the most intimate of my work. I talk about my life, but also about life and existence. I started doing more of them when I left Egypt (2003) to live in Paris as an artist-in-residence. In Egypt, I had a very different life, I was with people I’ve known for years – family, etc. In Paris I found myself in a completely different place and atmosphere with new people I had just met. It made me think more about life in general, about existence – not only my own – and the idea of starting all over, then leaving again, never really feeling that you belong to a place. I make the self-portraits in different cities. In each of these cities I felt that I was a visitor and I knew that I would leave soon. My whole relation to life is the same, for me it is about coming to a place that is not yours, then having to go.

There are definite references to Islam in your self-portraits. What is your attitude to religion?

I grew up as a Muslim, but my father was Christian before converting to Islam. So I had a whole Christian family on my father’s side and a Muslim family on my mother’s side. This made me close to both religions in my thinking. We used to celebrate both religions’ festivals, like Christmas and Ramadan for example. But this also made me question and be curious about all other religions. I’ve always had my own ideas about religion and I think all religions are really the same; it doesn’t matter what they’re called, as they’re all leading to the same goal.

The likes of David Lynch, Tracey Emin, Zaha Hadid, Jean Nouvel, Sting and Gilbert&George are just some of the illustrious cast of your series of portraits. Yet, the images range between the celluloid immortal and waxy death masks. What do these people represent to you?

They are all artists I like, but also iconic figures of our time. I wanted to do a close up portrait of them, to get close to their soul.

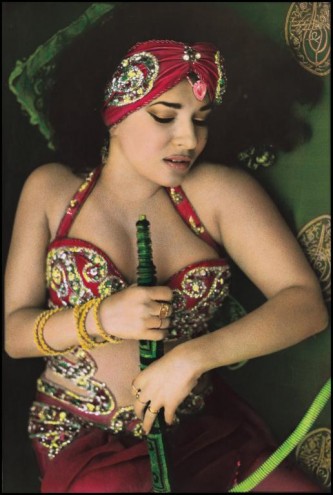

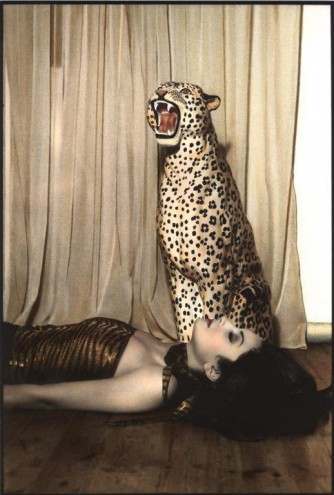

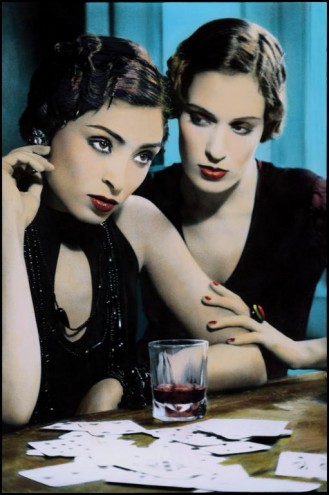

Your second series of portraits are less sinister, capturing a romantic melodrama of emotions: Love, passion, loneliness, moodiness, seduction, temptation... What is this change?

They are more narrative and they tell a different story. They show different emotions, where I ask people to play a character.

Yet, death and immortality remain an undercurrent through all your work, and your new book is entitled I Won’t Let You Die (Hatje Cantz). Are you scared of death?

I’m not actually. I think about it all the time and I already made peace with it a long time ago. For me, we die everyday when we go to sleep. When we die, it means that we come to an end. Why would I want to live more then my end? When we come to the end, it means that we have done what we were supposed to do.

One could do worse than having one’s soul snatched by Youssef Nabil’s camera. Encased in lovingly hand-coloured silver gelatin, one would be immortalised in the style of vintage celluloid heroes, in a crematorium shared by the likes of Louise Bourgeois, David Lynch and Jean Nouvel, with a score of Egyptian film stars and a chorus of broody eyes. Such a death wish is not maudlin in Nabil’s dreamy lens. As he says, death comes everyday when we sleep.

Nabil discovered photography in the early 1990s when he and his friends would stage scenes from the golden age of Egyptian cinema. He went on to work as an assistant in prominent photographic studios in New York and Paris, before returning to Egypt in 1999. Since his debut exhibition in Cairo in 1999, Nabil has exhibited widely from London to New York. At present he lives in New York.

As Matthew Krouse puts it in the Mail&Guardian, Nabil “learned three things from his predecessors: get the famous to sit for you, take evocative self-portraits and portraits of exotic unknowns”. Design Indaba’s questions reveal a photographer enraptured with the romantic.

After starting out staging photos with your friends in Cairo, you went on to assist the likes of David LaChapelle and Mario Testino. Can you give us an account of your early life in Cairo, your discovery of photography and how you came to be the rising star you are today?

My life in Cairo was very much inspired by cinema. I started taking photographs because of my love for cinema, which is very central to Egyptians. I would ask my friends to act in scenes that I would write and photograph, always in black and white. Then I had the desire to see my work in colour, but never wanted to use colour film. So, I decided to colour them by hand using an old photography technique. I wanted to keep this old feeling in my work, to have it received as a painting as well as a photograph. Then people started hearing about my work and asked me to take more pictures. I guess one thing led to the other and I found myself having my first show at the Cairo Berlin Gallery in 1999.

With your hand-painted photographic technique, you seem to be blending the two genres of painting and photography. Can you explain this approach?

All my work is first shot on black-and-white film, then I hand-colour each of the prints in my studio, using an old photography technique. I like to mix the old and contemporary. There is something that I always loved about old techni-colour movies, hand-painted movie posters and hand-coloured studio portraits. I grew up seeing them everywhere in Cairo and wanted to keep that in my work.

Your work is heavily influenced by the golden age of Egyptian film and you say that you live your life as if in a cinema. How did you come to be so enraptured with the moving image?

I grew up watching a lot of movies – old Egyptian movies specifically. It was one of my main sources of amusement as a child. I discovered death through cinema; that actually the actors and actresses I love are dead! Being in love with all those dead beautiful people was a shock for me. I wanted to meet the ones I love before they die or before I die.

In particular you really like Federico Fellini. What do you take away from his work?

I like his way of telling a story. He’s a brilliant storyteller. His colours, characters… You can feel he was a very sensitive person. I love the fact that he was very connected artistically to his wife Giulietta Masina, who was a fantastic actress, but also his muse. I love artists like him; his work and life were one. He had a unique vision of the world and I find that very beautiful.

You have now left Egypt and live in New York, via Paris. Yet there remains a distinctly Egyptian flavour to your work. How has Egyptian culture and society permeated your work?

In my work, I speak about issues that concern me. Even if I don’t live in Egypt, I feel Egyptian, but also Mediterranean. It is always about how you feel.

Your images slip between cinema and dream, dislocation and privacy, seeming both immediately raw and staged. What is the self that you present in your series of self-portraits?

It is part of me, maybe the most intimate of my work. I talk about my life, but also about life and existence. I started doing more of them when I left Egypt (2003) to live in Paris as an artist-in-residence. In Egypt, I had a very different life, I was with people I’ve known for years – family, etc. In Paris I found myself in a completely different place and atmosphere with new people I had just met. It made me think more about life in general, about existence – not only my own – and the idea of starting all over, then leaving again, never really feeling that you belong to a place. I make the self-portraits in different cities. In each of these cities I felt that I was a visitor and I knew that I would leave soon. My whole relation to life is the same, for me it is about coming to a place that is not yours, then having to go.

There are definite references to Islam in your self-portraits. What is your attitude to religion?

I grew up as a Muslim, but my father was Christian before converting to Islam. So I had a whole Christian family on my father’s side and a Muslim family on my mother’s side. This made me close to both religions in my thinking. We used to celebrate both religions’ festivals, like Christmas and Ramadan for example. But this also made me question and be curious about all other religions. I’ve always had my own ideas about religion and I think all religions are really the same; it doesn’t matter what they’re called, as they’re all leading to the same goal.

The likes of David Lynch, Tracey Emin, Zaha Hadid, Jean Nouvel, Sting and Gilbert&George are just some of the illustrious cast of your series of portraits. Yet, the images range between the celluloid immortal and waxy death masks. What do these people represent to you?

They are all artists I like, but also iconic figures of our time. I wanted to do a close up portrait of them, to get close to their soul.

Your second series of portraits are less sinister, capturing a romantic melodrama of emotions: Love, passion, loneliness, moodiness, seduction, temptation... What is this change?

They are more narrative and they tell a different story. They show different emotions, where I ask people to play a character.

Yet, death and immortality remain an undercurrent through all your work, and your new book is entitled I Won’t Let You Die (Hatje Cantz). Are you scared of death?

I’m not actually. I think about it all the time and I already made peace with it a long time ago. For me, we die everyday when we go to sleep. When we die, it means that we come to an end. Why would I want to live more then my end? When we come to the end, it means that we have done what we were supposed to do.