Senegalese ceramicist Fatimata Ly is committed to the creation of authentic products. Ly studied biology and biochemistry, but was drawn to clay – and even found that her methodology and understanding of minerals informed her ability to manipulate it. She pursued an education in ceramics at Central Saint Martins in London, where she learnt the importance of bringing together technical knowledge and cultural heritage. With her brand Fatyly, Ly brings to life contemporary products by infusing them with a strong sense of African heritage.

We talk to Ly about how she defines her brand and what it is like to be a creative entrepreneur in Senegal's capital city.

Have you always been creative and did your parents encourage you?

As a scientist, my father’s views did not align with art education. He did not believe in achieving in arts. For him the only route to excellence was conventional science. Therefore I was encouraged in the science route and I studied biology and biochemistry. But eventually I ended up to have strong interests in clay and I realise even more today how ceramics has a scientific methodological framework from its mineralogical components, plasticity, heat shock resistance to shrinkage... In fact I discover everyday that I will spend my life doing ceramics.

What inspires your work?

Today my work is mainly inspired by Senegalese women’s lifestyle. I have a passion for tradition and authenticity, which makes me revisit the Senegalese traditions from hairstyles to garments with the Nguka collection.

How do you describe your aesthetic?

A difficult question as it isn’t easy to analyse one’s own work. I will attempt to describe it briefly. Fatyly’s originality is the willingness to mix modernity and authenticity through the material, shapes, cultural background and the craftsmanship. So far three words seem to govern Fatyly's aesthetics.

Firstly, tradition – known in the Wolof language as “Thiossane” – inspires the work with a strong intention and purpose. Fatyly wishes to bring a new brand story with a unique vision to tell the story of African heritage through porcelain ware and earthenware.

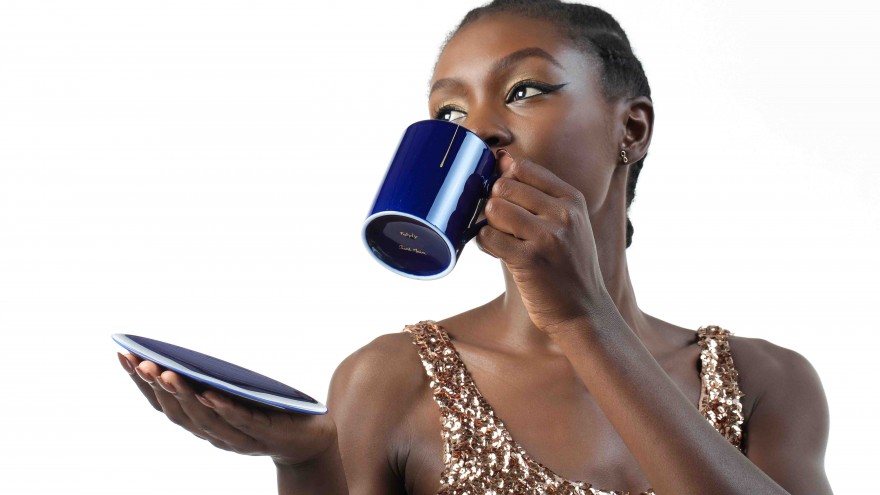

Second, authenticity – with the use of raw materials to make products such as the Pounding Light to symbolise imperfection through surface roughness or the porcelain of Limoges for Nguka collection to design graphic elements on elaborate shapes and finish. The mark of authenticity is revealed through the use of vivid hues of heirloom fabrics and jewellery such as blue, black and yellow. And the brand values knowledge and skills to ensure the survival of traditional forms of craftsmanship.

Thirdly, lifestyle is revisited through cultural interest, research and understated through the use of colour to symbolise elegance. The blue cobalt is reminiscent of Indigo, an ancestral African colour used in garments and accessories. Fatyly considers dinnerware and tableware as fashion products and therefore as replaceable, interchangeable items. In fact the brand even refers to them as collections. Fatyly elicits emotion by using distinctive visuals, shapes to enhance the consumer’s lifestyle with exclusive, qualitative products.

Does the word Nguka mean something?

Nguka was borrowed from the Wolof language. It is a horn-like hairstyle worn in the past by Senegalese women on special occasions. Gold ornaments were very often used to enhance the Ngukas.

How do you describe the experience of living and working in Dakar and Senegal?

After living abroad for more than 20 years, living in Dakar has been very easy. The challenges are more based on the size of the market and also on the facilities and equipment, as there is not a large community of ceramicists. As for the market one needs to rely on a more global market in order to survive as a designer.

What is your biggest challenge?

Today the biggest challenges for Fatyly is to produce locally and the business is currently looking at opening a ceramic plant in Dakar. An other challenge is to be an advocate of the pleasure of a plate and discuss the need for a conversation between patterns, textures and food on plates and dishes. The food world, especially the gastronomy protagonists are more inclined to use whiteware exclusively therefore introducing a debate around food, graphics and textures could be a rewarding challenge.

Has the creative landscape of Dakar changed much in the last five years?

Yes, I am amazed by the increasing numbers in art especially in photography or fashion. They are all not only bringing a language shift but also reinterpreting cultural themes through a contemporary perspective.

Why do you think people are so excited by what is coming out of Africa at the moment?

I would simply say that each part of the African continent has to tell its own story. The variety of tales makes life a little more interesting hence keeps the excitement.

Are you very influenced by the places you see and people you surround yourself with?

I would say that I am more people oriented… I have a passion for cultural heritage in terms of values, customs, etc. I do believe that it informs us on who we are as human beings and allow us to understand, to value and to care for it through food, literature, fashion, photography…

Who do you think is doing amazing work in Dakar at the moment?

So many are doing amazing work!! I would say in design Ousmane Mbaye is someone to observe as his work seems to move from colourful, textured furniture to simple lines; I am curious to know the next stages of his work. In photography, Siaka Soppo Traoré’s use of form and lightness brings a energy to the Dakarois photography landscape.