From the Series

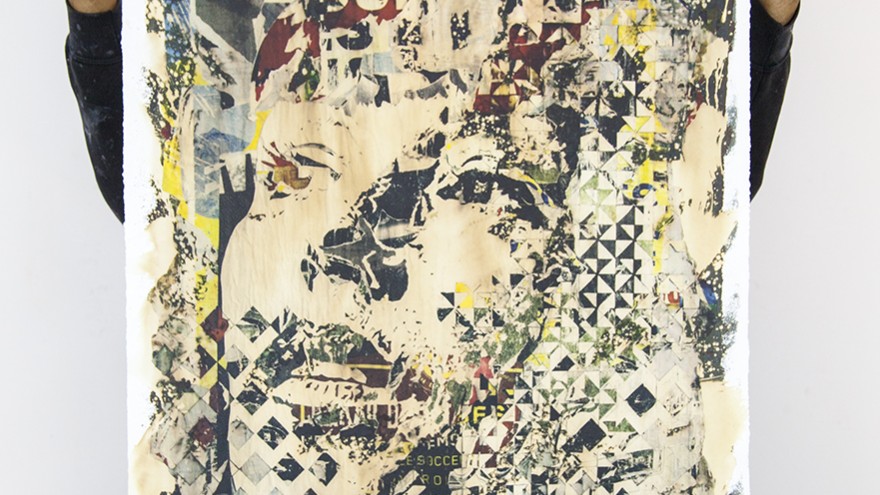

The title “street artist” does not do Alexandre Farto, AKA Vhils, justice. Using city walls and billboards as his canvas, Vhils discards the standard spraypaint can in favour of a chisel, hammer and drill. He has pioneered a new way of making his mark in giant-sized artworks carved, drilled or even exploded into form – a process he calls “bombing”.

Vhils began using explosives to get across his point that “at times of social and economic crisis everything which we hold as certain becomes highly volatile”. It’s not just city residents that have started to take notice; he’s taken his art into galleries around the world and produced videos for the likes of U2.

In the third of our WeTransfer Featured Artists series, we asked him what’s behind his vigilante aesthetic.

How did you get into being a graffiti writer?

My interest in graffiti started sometime around 1997. There was this mystique that surrounded it. It was illegal and secretive but it was done out in public. When I was 13 I started bombing for real and over the next few years became fully immersed in the illegal graffiti scene in Lisbon, painting mainly trains. It was only around 2004 that I began experimenting with other media in the public space. I still regard graffiti as my first art school, as it gave me many skills I’m still using today. It was also pivotal in giving me a sense of how to use public space and most of the concepts I use today in my artwork.

You use an unusual carving technique. Can you explain how you do this, what it involves, what tools you use etc?

I use carving techniques in various bodies of work, mainly walls, billboard posters and wood. I usually apply a few layers of paint in different colour tones to convey contrast and depth, and then begin the carving process. I'll only remove a few of these painted layers, while leaving the rest to help bring the piece to life alongside the wall’s own layers. The main areas are usually done with rotary hammer drills, while the more delicate areas are tapped out with the aid of hammer and chisel, but I’ve worked on a few walls simply with the aid of utility knives. The choice of technique always depends on the wall's consistency and characteristics.

Tell us about growing up in Seixal [an industrial city nearby Lisbon]. How did it influence your outlook and your work?

Seixal is a small suburban town, located across the river Tagus estuary from Lisbon. Beyond the industrialised town, the area around Seixal used to be mainly farmlands which started to disappear when I was growing up. The process of urbanisation was very fast and badly implemented – regardless of cultural or social specificities.

A major influencing factor was how I came to realise that walls become the repository for what takes place around them.

I was fascinated by the remains of the old political murals that had taken over public walls after the 1974 revolution. By then these were decaying and partially hidden by advertising posters. These, in turn, became hidden beneath layers of graffiti. Then the city council started painting over the graffiti, and so I observed how these walls in the course of a few years had gained a number of new layers, becoming thicker over time. When I began working with stencils, it occurred to me that instead of adding more layers to these walls I could use what they already provided, exposing some of the past history they had managed to capture in the process.

You talk about the “aesthetics of vandalism”. What does this mean and why is it important to you?

This is a concept developed from graffiti that basically highlights the act of creating with means that are regarded as destructive. Graffiti is fundamentally an act of aesthetic vandalism. It defaces while being an act of creation. I like to play with this notion, to use it as a conceptual tool that emphasises the message I’m trying to get across. I distort the notion of vandalism while turning it into something positive, and this concept has become the backbone of my work. Even when you’re writing or drawing on a white sheet of paper you’re essentially subtracting light from its background. Creation is transformation, and transformation always entails destruction and replacement.

What do you think binds all street artists, no matter what their nationality?

Probably the fact that, despite coming from different backgrounds and cultural contexts, they all seem to view public space as an interesting place to work in, where you can engage directly with a wide audience. That and the fact that we are probably all misfits...

What is one of the most challenging works you have made recently?

The work and entire set-up of my large solo show last July at the EDP Foundation in Lisbon was hugely demanding and involved the collaboration of many people, both from my studio and the museum itself. We spent months working on it. On a different note, the video I produced for U2 (“Raised by Wolves”) was also very challenging as I only had two days to shoot the whole thing and everything had to be done just right. But I sometimes find the ordinary, mundane things of the day-to-day a greater challenge...

You've made street art in cities all over the world. What does making street art in a foreign city reveal about the city to an outsider?

The act of creating in the public space can be very revealing in itself, especially when you start opening up the city’s walls and exploring the layers hidden beneath – these alone tell you a lot about what went on in that place over the years as they absorb the history of a place. But I also like to do some research before I arrive and once there I also like to speak with people from various backgrounds who can tell me about their city. Material reality says a lot about a place, but speaking to people, listening to their stories and memories is invaluable.

You’ve used explosives – wow! Tell us about that?

The use of explosives occurred as a natural development from carving walls and other surfaces with industrial tools. At the time I was looking for a process that was even more destructive in order to emphasise a particular point – mainly that at times of social and economic crisis everything which we hold as certain becomes highly volatile.

Creating with explosives has been very interesting, but the result needs to be captured on video for it to work.

I started using them in late 2010 for a specific project titled “Detritos” (Detritus), which involved creating three videos for an exhibition. Since then I have used the same technique to create other art videos and music videos, always in collaboration with an expert in pyrotechnics who helps me to create controlled explosions. In very simple terms, the pieces are carved beforehand and then rearranged and packed with explosives along those carved lines, which are then detonated.