First Published in

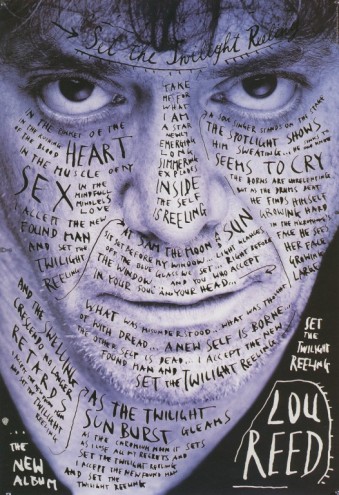

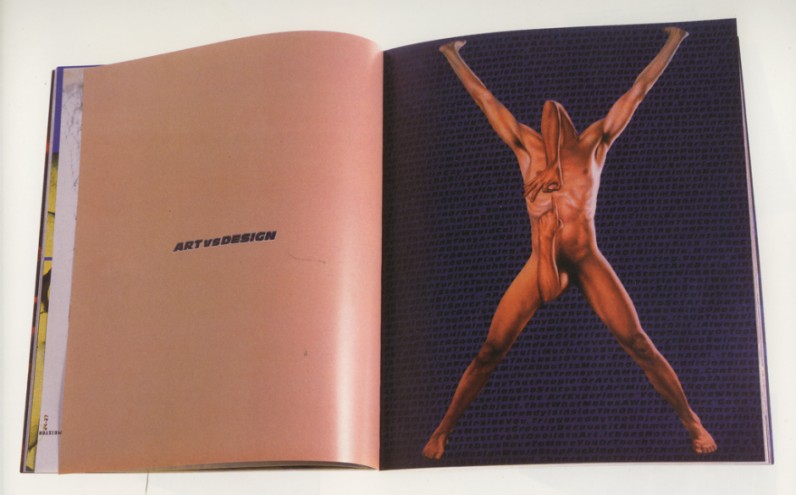

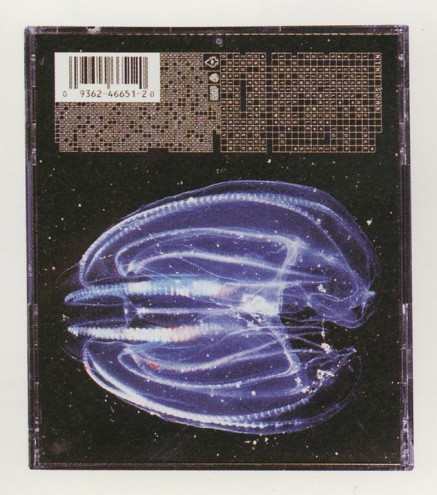

Yes, Stefan Sagmeister is a great designer. He's done album covers for David Byrne, Lou Reed and the Stones, he worked for the Leo Burnett agency in Hong Kong, he produced a great book of his work - Made You Look -and he now runs his own, successful design studio in New York. Far more interesting, however, is the way Sagmeister uses his abilities to design a better world. And no, we don't mean a better-looking world. From the Move Our Money campaign, which aims to funnel Pentagon funds into education and healthcare, to the mountains of pro bono work he's done since September 11, to the fact that the guy apologised profusely for setting an early morning time for this interview, Stefan Sagmeister shows genuine concern for other people.

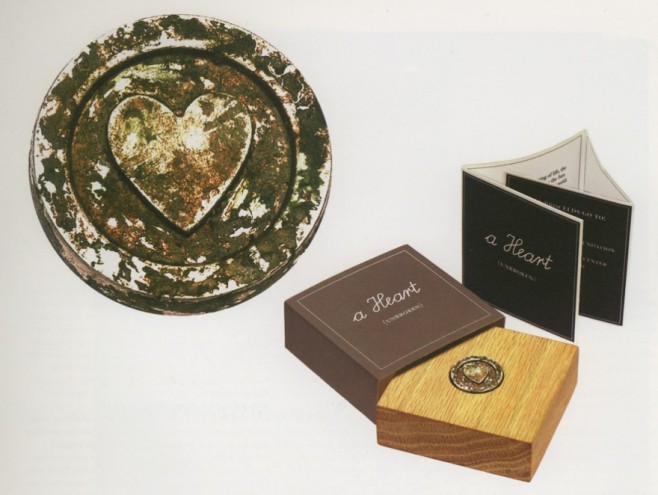

I've read a lot of conflicting stories about the pin you're working on, "A Heart (Unbreakable)", so I wanted to ask you…

[Chuckles] Yah, I know, let me tell you all the stories from the beginning… His work has been exhibited in the Design Museum and the V&A, London.

Okay, we had the idea right after September 11 to make a pin out of the metal from the World Trade Center. I assumed there would be a lot of metal, and I was right. As it turns out there were 100 million tons of metal - much more than anyone could do anything with.

So … we decided to make a pin, but make it a BIG project, producing hundreds of thousands of them to sell for charity. I knew at the beginning that we shouldn't talk about it before it was done, but, then I thought that the press might help us get the permits for the metal. So the New York Times did an article, and featured the pin heavily. Then it took ages to get the metal. One junkyard promised us a lot, then ignored us for months. So, in the end it took until April for us to get the metal. Then it ended up taking three weeks to prepare the metal.

Then we set about looking for distributors with many outlets - we talked to everyone from the postmaster general to Citibank to the Gap. By this time it was the end of April or early May and no one cared - companies with a genuine interest in doing something already had, and those who had done nothing had never been interested.

It's too bad that it didn't work out, but I did learn something. In October, November, and December, I was doing almost only pro bono work … I should have cut down on projects and focused more time on the pin then. I'm sure it would've been a big success and raised a lot of money. So, now it's on the shelf. I got 25 books in today to send to all the people who worked on the project, but unfortunately nothing came of it.

How do you think design has changed since September 11?

Well, in my case, I had taken the year before off, so many of the changes, business-wise, were already in place. Also, I'd already decided that I wanted to do less business with the music industry and more work for causes. September 11 just underlined that decision.

In general I think it definitely meant that the 'high-flying' times of design were officially over, but, again, they were a bit over already before that. September 11 simply underlined it. Now most design companies [in New York] are not doing well. They are affected creatively, not just economically. I talked at a conference a couple of months ago, and there were only a few graphic designers - the rest were new media people. I was really surprised, there was so much more quality than there was two years ago. Two years ago, the new media people were too busy raking in the money!

I wanted to talk to you about that year off, too. Now that a bit of time has elapsed, how do you feel about that decision? Was it helpful, creatively? Was it the right decision?

Oh, it was definitely the right decision, I can say that 100%. I had been playing around with it for a while, and then I just had to do it when I realised that I was losing the fun of design. From that point of view, I had to do something, and I definitely won some of that fun back. Not that I expect that every day I come into the office should be hours of fun, but I'm talking six-month long stretches…

I'm not sure if the work is better now, I think it's still too soon to tell. We've been back in business since October, and some projects have been published, but not a lot, so it's really too early to say. But I'm definitely happy to be back in business. We are three here as a team and the people I work with are fantastic. I have to say that, you know, because they are right here next to me. [Laughs]

But really, during my year off, I was experimenting by myself a lot and everything dragged. Things go so much more quickly with a team. I'm very happy about that.

You're from Austria and you've lived and worked in Austria, Hong Kong, and New York. Based on these experiences, do you see design as a sort of universal language, or does it change from region to region?

I think it's a universal language. I mean, of course there are cultural differences - differences in how colours or forms are perceived - but I think that these are overplayed. A good example is the difference between book and CD cover design. They're very comparable design projects, but for some inexplicable reason, every market thinks that books need different covers, but CDs stay the same. It's much more to do with how things are distributed. Local publishers have power, and the distribution of power within the publishing industry is different from within the record industry. In the end, it has nothing to do with local problems or tastes, even though the publishers will say that it does.

In Hong Kong, I worked on an international advertising campaign. It was an unbelievable pain in the ass. Unbelievable. Everyone is always saying, 'you can't do this here, and you can't do that there.' I even once had a German creative director say, "Oh, you can't have all capital headlines in Germany", not realising that with a name like Sagmeister, I might know what you can and can't do in Germany! I didn't have very nice things to say to him!

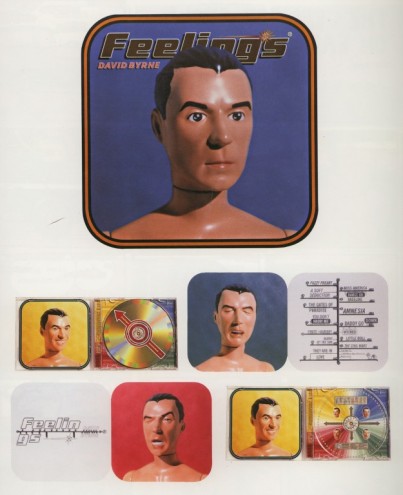

I know you've worked on David Byrnes' CDs; have you worked on any of his book projects?

Yes, I did one book with him, called Your Action World, with the subtitle: Winners Are Losers with a New Attitude.

How was he to work with?

I loved it, loved it, loved it. You know, his label warned me about him at first. They said he's an artist himself, so he's difficult to work with, etc. So I went in with very low expectations. But it was exactly the opposite. He genuinely has the quality of the finished product in mind, not his ego or anything else. And he gave us an unbelievable amount of freedom. We designed AND edited the book. He just brought in two boxes of artwork and said, "Go." Of course we talked about what the artwork was about and all that, first, but it was a totally easy collaboration. And … he's a really, I don't know … sweet person - a pleasure to be in a meeting with. Also, it's completely unheard of to work with a musician who's so visually sophisticated. I came away feeling like I had really learnt something.

Tell me about the Move Our Money campaign; first off, how did you get involved?

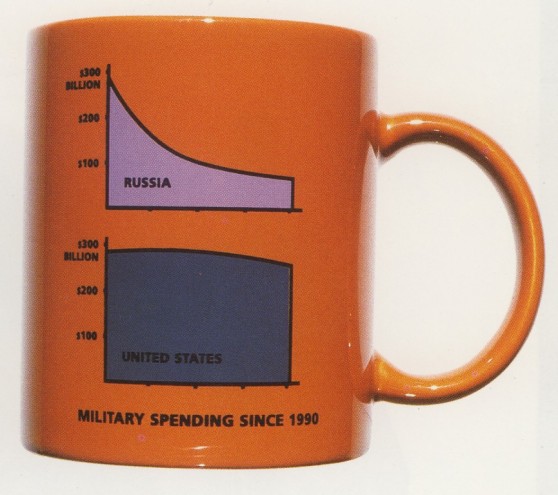

Well, I met Ben Cohen (at that time he was still with Ben & Jerry's) and we talked and we liked what the other had to say. He told me about "Business Leaders for Sensible Priorities" - bad name, but a good group - which is basically a group of about 500 business leaders who know enough about accounting to say that the amount of money going into the Pentagon's budget every year is ridiculous, that 16% of it could easily be funnelled into healthcare and education. Of course, after September 11, this platform was not destined for success. So, now the group has been renamed the True Majority. The Move Our Money idea is still a part of it, but the platform is broader now. It includes 10 points, all geared toward preventing another 9/11 from happening, from the ground up, without military involvement. The points include everything from ending world hunger to paying UN dues.

I think the group is great, not only because I agree with their principles, but because, since it's made up of a group of business people, they have the money, PR, and marketing to make a serious campaign. Right now we're addressing the practical steps: how do we get emails? That's a big one. We are collecting them in a variety of ways. First, we designed unusual cars - one is a huge pig, for example - to parade around the country. One goal of these cars is to get TV attention; the other is to get emails. Then, we're hitting the music festivals. We've designed 10 carnival-type booths to take to festivals, with games. Anyone can play, but if you give your email you can win the prizes more cheaply.

How do you feel about design activism in general? Is it better to do your own activist work or to use your design skills to help an existing group?

Well, in our case, our success rate with our own activist projects is zero. We've tried a couple and failed on both. It's very hard…

Do you feel that people don't take you seriously as an activist, coming from a design background?

Yes, there's that, and then there's the fact that when you have a regular studio running at the same time, it's hard. When you do your own project, there's no deadline, which makes it easy to put aside. If you're doing work for a non-profit, there is a deadline, so you get it done. There are those who manage to do it, though. World Studio is a good example; they're a design company in the mornings, and in the afternoons they are an activist group with different goals. In general, with design and activism, there's the challenge of doing things that are effective, not just good-looking in an annual. You look at a lot of pro bono work in design annuals and there are ad companies that get non profits to go for an idea, and they do it free because thy have some deal with a printer, and then it doesn't get distributed at all because really they just wanted to do the work to win some award or something.

What are your thoughts on the First Things First Manifesto, both for yourself and the design community at large?

Well, I love that they did it, and I think the people who were behind it were very sincere. I never signed it, because I was never asked to, and now, you know, it's pointless. It's big enough as it is. Of course, if I were asked, I would still sign it, but I don't really think it's necessary. With regard to design, I think it's a big indicator that these things have such a resonance. I mean, it was published in six different magazines. I don't know any other issue that got published that much or prompted so many letters to the editor. You know, the 80s were all about lifestyle, and the 90s were all about typography. Maybe this decade will be about this [activism].

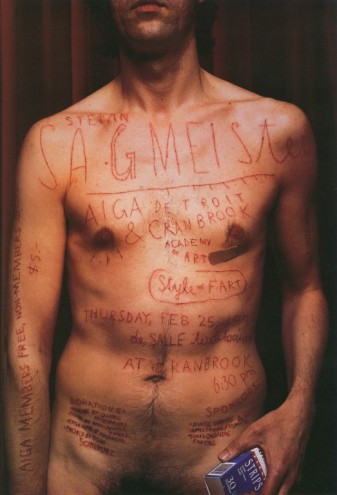

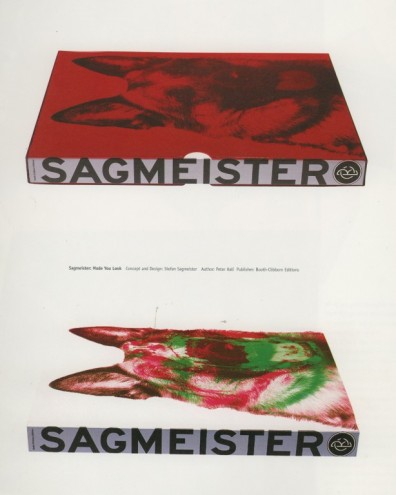

A graduate of the Hochschule für Angewandte Kunst in Vienna and the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, Austrian expat Stefan Sagmeister cut his teeth at Tibor Kalman's legendary M&Co. Kalman observed of his one-time employee that he was less a designer than an inventor. This is evidenced in Stefan Sagmeister's painstaking methodology: he minutely researches design tasks, formats, materials and functions. Stefan Sagmeister founded the New York-based Sagmeister Inc. in 1993, specialising in graphic and packaging design for the music industry. Despite widespread critical acclaim, he has refused to enlarge his small studio. The hand-scrawled subtitle to his first book, Made You Look, sums up the candid humour of the designer. "Another self-indulgent design monograph (practically everything we have ever designed including the bad stuff)." Stefan Sagmeister will be a speaker at the 6th International Design Indaba, February 26-28, 2003, Cape Town, South Africa.

Amy Westervelt is the Managing Editor of Soma Magazine, a San Francisco-based monthly profiling avant-garde arts and culture around the globe. "It's a glamorous job," she says, "but at some point, I would like to give it all up and pursue my true passion: bowling."