Paul D. Miller: The recent discovery of the colorings that decorated the Terracotta Warriors that surrounded the grave of Emperor Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China, tell us that China’s tradition of using the arts to buttress governance, power, and the central government go back to the origins of the nation. I tend to think of your work as an elusive counterpoint to the premise that art can speak truth to power. What inspires you to look at the history of China and Revolution for material?

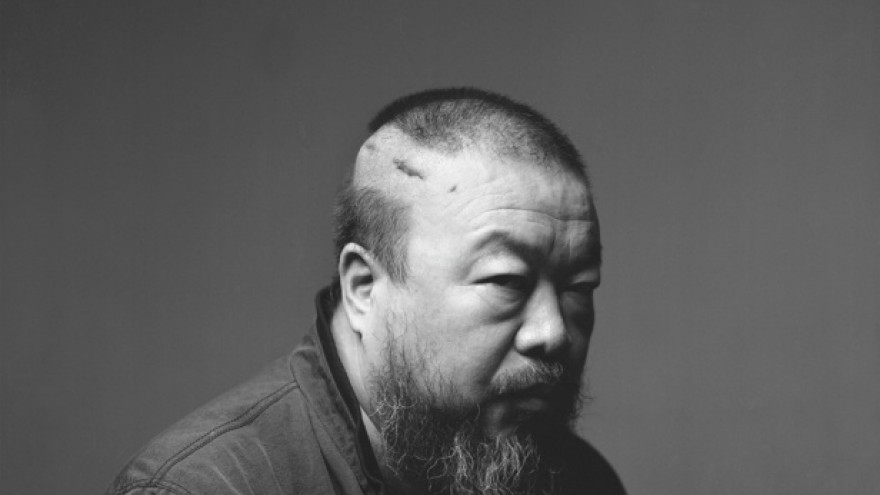

Ai Weiwei: China’s culture and history are closely related to my living environment. This country is my birthplace. It is also where I grew up. Its culture and history shape my relations with family, friends, society, and daily life. It is also the main reason that leads me to my current condition. Through my work and ways of expression, I strive to engage in dialogue with the society that I am living in. I hope that my work expresses my worldview and encourages people to exchange ideas.

PDM: Special “zones” have been a feature of the modernization of China for hundreds of years - what do you think about the role of art in China’s geography and history? Does it affect your practice? Especially in light of the art projects where you have had a tremendous amount of people travel from China to Germany for dOCUMENTA, Fairytale, or the earthquake rebar materials in your works about the Sichuan earthquake of 2008.

AWW: China has a rich history that has spanned millennia. It consists of the histories of many nations and regions. My understanding of Chinese history is limited. So far, I have only scratched its surface; I wish I could find out more. I gain insights about China’s history and society working on projects such as Fairytale (2007) and Citizens’ Investigation (2008). Along with many architecture projects, online initiatives, and exchanges with netizens, they are all learning experiences for me.

PDM: With the rise of digital media barriers - “The Great Firewall of China” - artists, more than ever, have found that art is an elusive quantity, difficult to corral and control. How do you feel your work relates to current digital media projects, and how is it a critique of the urban landscape - for example, some of your works like “Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn” or your photographs of New York from your time living there?

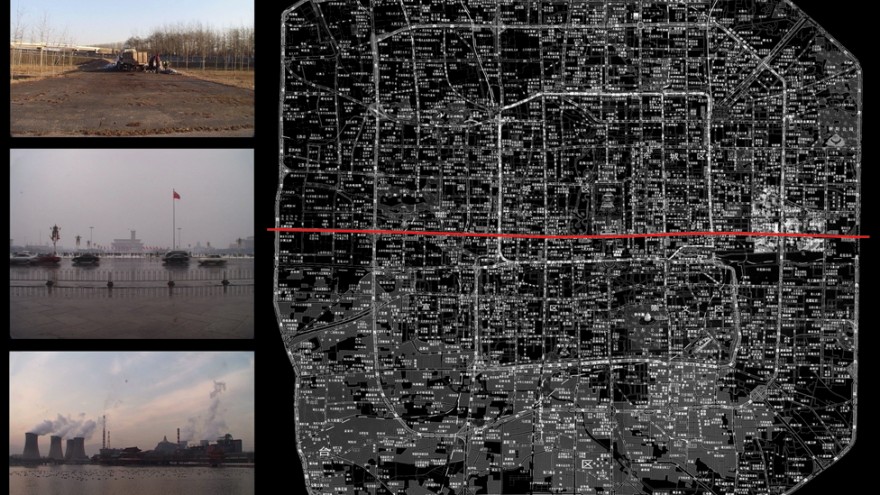

AWW: Many of my photography and video works relate to the current conditions of cities and their changes. I created works such as Beijing 2003, Second Ring, Third Ring, Chang’an Boulevard, and Provisional Landscapes with the intention to express and document these changes. We live in changing times, and many people experience the challenges that come with it. In the face of uncertain futures, no one will know what to expect.

PDM: You have a famous phrase that people often quote: “Without freedom of speech there is no modern world, just a barbaric one.” How do you feel about that statement after your experiences in the secret prisons?

The freedom of speech is an important yardstick for a society’s level of civilization. A society is healthy only when it allows its members to discuss their thoughts openly. This is also the only way that a society can gather consensus, let everyone express his or her wish, and foster creativity. However, China restricts the society’s freedom of speech.

The Communist Party imposes these limits because it lacks confidence towards the future and has no ideals. Nowadays, China is experiencing the detrimental effects of such decisions.

Its citizens have no creativity. There is no motivation in participating in politics, nor social responsibilities. There is no media freedom. As a result, the society is corrupt and lacks productivity. It is unable to adjust itself for progress. This will lead to the country’s eventual downfall.

PDM: Your aesthetics are grounded in disciplines as diverse as poetry, architecture, rock music, photography, sculpture, and installation art. Which one acts as a main catalyst for you?

AWW: Behind all these categories, the most important theme is individual freedom. Our lives are bound by physical limits, familial ties, political conditions, and geographical restrictions. Individual freedom takes us beyond them all. The demand for individual freedom leads us to different realms, and it enables us to participate in social events. By participating in the society we live in, we understand our conditions and the way we relate to the world. The categories are therefore not important. What is important is that we actively express our thoughts and wishes, in every realm that we can access.

PDM: How do you feel that the rest of the world views the rise of China and the role that contemporary Chinese art will play in the interaction of economics, globalization, and the fact that China has become the world’s production lab? Your work at The Tate Modern, “Sunflower Seeds,” hints at this. I’d love to hear how your view of the concepts of “original” and “copy” reflect one another - especially since your studio is called FAKE.

AWW: The rest of the world understands little about China’s changes and the possibilities and crises that come with them. China seems unpredictable because it has a distinct culture and social system. It is still a mystery to other parts of the world, even though the veil of China has been lifted many times as a result of globalization. The biggest obstacle in interacting with China is the difference in perspectives about basic values. These include issues such as human rights, the concept of law and constitution. The importance of elections, transparency, legal procedures, an independent army, and the judicial system is not regarded as highly in China. These core values are the most important evidence of the health of a society, quality of life, and security. A clear understanding of such differences will help the rest of the world understand China and all that is happening to the nation.

PDM: With places like Zhongguancun (the computer hardware shopping center in the heart of Beijing that is one of the largest of its kind in the world), one can see how special geographic areas have evolved out of neighborhoods like the hutongs of old Beijing. Specialized spaces like the Bird’s Nest or Ordos 100 are reverse cities - they are built first, then become the centers of reverse-engineered cities that fill around them as needed. What do you think of the future of Chinese cities? What role does art play in the urbanization of China, from your point of view?

AWW: So-called Chinese art and culture is under control of the Party. They exist to serve the official agenda. I call it fake art and culture. For decades, the Party reaps political benefits at the expense of the people’s knowledge, happiness, and imagination. As a result, modern Chinese culture is weak and lackluster. My musician friends are banned from playing concerts in China because they share the same views as I do. My name cannot appear on the web, because my opinion is different from the Party. All movies in China are censored. Out of 600 movies produced in China, only 60 are allowed to show in theatres. For example, our documentaries can only be distributed online. This is the only way that they could be seen. Beijing is constructing a 100,000 m2 modern art museum, yet it will not feature any of my work. The so-called culture nowadays is only a fake one with a superficial front. It is an empty lie. This country spends a lot of resources and effort on gaining soft power over culture. The hope is that it can be the last lifeline for the Party’s survival. Obviously, the idea will fail.

PDM: What are some contemporary Chinese bands you suggest people check out?

AWW: I would recommend Zuoxiao Zuzhou (左小祖咒) and also the group Ershou Meigui (二手玫瑰, Second-hand Rose), who is playing in Brooklyn in the fall.

Interview published with special thanks to Paul D Miller (aka DJ Spooky), Origin Magazine and Ai Weiwei.