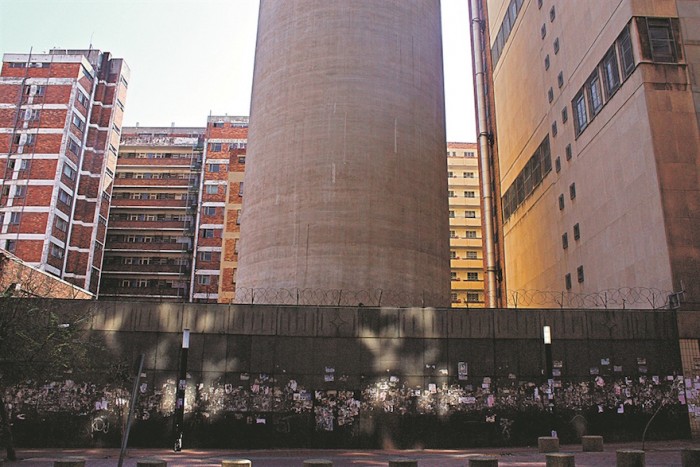

In 1968, with apartheid in full swing, architect Jan Heineken set to work on what was to become Africa’s tallest structure. Over the next three years the JG Strijdom tower climbed 90 stories above a then swinging Hillbrow, to 270m, a quarter kilometer into the heavens. “A revolving restaurant seated 108 people in luxurious comfort,” puffs a promo from the period, “and offered an unrestricted 360-degree view of the City of Gold as well as superb service with at least one waiter to every 10 visitors.”

No corners were cut. The interiors and furniture were designed by celebrated South African artists and the décor was “the ultimate in comfort and luxury”. The restaurants and lounges were decorated with “magnificent Ernest Ullmann appliqué wall tapestries depicting South African bird life, the history of communications and scenes of early Johannesburg”.

The tower would soon become Africa’s most popular tourist attraction. And then, quite suddenly, just 10 years later, it was closed to the public “for security reasons”. It has been closed ever since.

Twenty-eight years later, what is now called the Telkom Tower, or Hillbrow Tower, has lost none of its currency as a symbol of Africa’s economic might. Tourists buy postcards of it and we wear catchy graphic “Love Jozi” T-shirts and buy cheap Chinese-printed canvasses of it on Lilian Ngoyi Street – all the while complicit in an urban narrative that could be titled, The Emperor’s New Skyline. To retain our faith in the myth of this towering citadel, we must stay blissfully ignorant of the perilous realities crawling around its base, the hollowness of its promise and, of course, of the trifling inconvenience of its closure. We have our Big Ben, our Statue of Liberty, our Eiffel Tower, only we can’t get in.

Johannesburg is not alone in its tale of inner city decay, dereliction and urban sprawl. Cities worldwide have succumbed to demographic centrifugal quakes. Some have recovered, others have resisted.

But Jozi raises the farce to hyperbole. The arrival of many thousand other Africans over the past 23 years has proved more a ridiculous tale of Babel than one of ubuntu. If I think back on the rainbow nation, it takes the curious form of a musical. As South Africans we’re all too good at treating aspirations as realities. Apartheid and its somewhat mystifying resolution has left us (whether victims or perpetrators) all too adept at living duplicities, and this city is one of them.

In a metropolis that barely notches up 130 years, way too much has been boarded up, forgotten, shut down or is eternally pending. Little still stands of what was just a frontier mining town until World War 1, but the century that has passed since then has left us with a fairly thin architectural legacy. This splits fairly neatly into three vernaculars – that correspond to the world’s, and specifically the country’s economic and political events. As a British colony until 1961, Joburg’s Georgian and Art Deco buildings downtown and in its wealthier suburbs have lasted fairly well. However, it is the modernist period, from the late fifties to the seventies, that define the city’s character most distinctly. The rand and gold prices were high and, until the real impact of global economic sanctions kicked in, in the early 80s, the city boomed, rejecting passé fussy decoration in favour of clean lines and new materials. Peer beneath the veneer of dirt and neglect, Jozi is largely precast concrete. And while this appears all too banal to us now, in its heyday it was thrillingly futuristic. Hard as it is to imagine, Park Station and its rotunda, unveiled in its current form for Queen Elizabeth’s first visit in 1947, was pure science fiction.

The metropolitan suburbs of Braamfontein and Hillbrow that sprung up around it were drawn largely from the tropical modernist movement in Brazil. We see lots of concrete breeze blocks – far more sustainable than glass buildings with power-gobbling air conditioning – along with the raised colonnades, surface detail and bold, precast concrete forms straight out of Sao Paulo. The resemblance is no accident: the catalogue from an exhibition entitled Brazil Builds, was required reading at the Wits Architecture School in the sixties.

The city’s architecture since then is barely discernible. Most of it is a low rise sprawl that is more concerned with paranoid responses to a security crisis than anything resembling civic pride or identity. Styles are often derivative, pastiche and quite haphazard.

So, on closer inspection, our apparently timeless skyline really spans a brief 15-year spurt of bold national hubris – from our declaration as a republic in 1961 to the Soweto Riots in 1976. The JG Strijdom Tower was one of many monuments and arteries named for apartheid leaders. Many have since been torn down or renamed. But for the large part, Jozi’s unforgettable leitmotif – its skyline, is a tragic anachronism, an outdated projection of something we once thought we were and that, for lack of any monumental contemporary replacement, says little about who we are, where we’re going, or what we hope for.

That was 40 years ago, a mere blip on the timeline of a metropolis, and so I thought to start counting from the top down and explore 10 of the city’s mothballed gems. And the further I travel along this Hit Parade of Vacancies, the more their collective significance grows nothing short of frightening.

Beneath the southern slope of Hillbrow hill lies what was once a miniature Central Park for the city – Joubert Park. It has descended into a den of dirt and danger. The once envied apartments surrounding it are now slums. Just north of the park, the once beautiful Wolmarans Street Synagogue is in bad repair and has since its closure become a nightclub and an equally raucous Pentecostal church. At the southern side of the park, the Johannesburg Art Gallery clings to its turf, only partially open and tragic.

The building, which was completed in 1915, was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, who also planned and designed much of administrative New Delhi. It was somewhat doomed since its unceremonious opening in the midst of World War 1. Working in the northern hemisphere, Lutyens intended the building to face north, on to the park. However, JAG, as it’s known, was built the wrong way round, with its grand facade facing the railroad tracks to its south. The building was not completed according to the architect’s designs and no part of the museum was broken down to let in the light, leaving many of its 15 exhibition halls and sculpture gardens dimly lit.

Currently, its main challenge is one of water damage, due to the theft of the copper sheeting that seals its roof. Damaged pieces include 17th-century Dutch paintings, 18th- and 19th-century British and European art and 19th-century South African works, along with a print cabinet containing works from the 15th century to the present. The notable collection of works by Auguste Rodin, Pablo Picasso, Camille Pissarro, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Herbert Ward and Henry Moore, and South Africans such as Gerard Sekoto, Walter Battiss, Alexis Preller, Sydney Kumalo and Jacobus Hendrik Pierneef are rarely seen and the gallery’s future is uncertain.

Head south and an even older structure stands boarded up and vandalised, on the corner of Marshall and Goud streets, the Three Castles building. Covered in graffiti and surrounded by barbed wire and rubbish, its mood is positively eery. The charismatic building with its three turrets was constructed in 1894 for the manufacturers of Three Castles cigarettes. It was taken over and reopened by president Paul Kruger in the past few years of the 19th century. The building has since manufactured bras and industrial piping and was, for 25 years, a somewhat tacky gay dance club called The Dungeon. Despite appeals to preserve its heritage, the building remains in danger.

In downtown Joburg, the ghosts of the city’s once grand hospitality are everywhere. The Carlton Hotel opened in 1972 as part of the Carlton Centre complex. First conceived by one of the city’s founding fathers Barney Barnato in 1895, the luxury six-storey hotel boasted an early form of air-conditioning. It was demolished in 1963. In its latest incarnation the five-star hotel housed 670 rooms on 30 floors and was regarded as the finest in South Africa, hosting dignitaries including Henry Kissinger, François Mitterrand, Hillary Clinton, Margaret Thatcher, Whitney Houston and Mick Jagger. Its restaurant, The Three Ships, was one of the best in Johannesburg. It closed in 1998, along with its chic adjoining boutique hotel, the Carlton Annex (full disclosure, my father Lionel Levin, designed these interiors and has been a great help in the researching of this article).

Kerzner really thought he could build a five star luxury hotel in the middle of Johannesburg

The Johannesburg Sun Hotel on Jeppe Street, I learn on a bitter blog titled, The Death of Johannesburg, was one of hotelier Sol Kerzner’s greatest follies. “Kerzner really thought he could build a five star luxury hotel in the middle of Johannesburg in the mid 1980s, and that it would remain as a standard bearer for his Sun International Group. But, of course, nothing could withstand the onslaught of the new South Africa and, very quickly, as central Johannesburg’s complexion changed, fewer and fewer tourists came to stay at the hotel. It turned a roaring loss – having cost untold millions to build – and eventually Sun International abandoned the building and it closed down, with the company just writing off the millions it had put into the site,” the blog’s author writes.

“The Holiday Inn Group then bought the empty building, and tried to turn it into a ‘Holiday Inn Express’. This also proved to be a dreadful flop, and the hotel was closed down and emptied for the second time. It reopened the building in 2002 as the KwaDukuza Egoli Hotel, but this also failed.”

Today, the 20-storey building stands desolate, boarded up and empty.

Head west to Newtown, where there has been some successful reinvention. However, the number of failures to launch lends a certain scepticism to the prefix “New”. But Newtown is home to the boldly titled Museum Africa. Far from a shrine to the continent, this sad, neglected space is a monumental anthropological faux pas. “Bushmen” are displayed with animals in the natural history section and the institution is an anachronism among contemporary takes on the continent.

As Steven Sack wrote in the Mail & Guardian: “It is a large building with serious problems such as rising damp, inadequate staff to care for the collections, and an architectural design that is not helpful for the display of exhibitions and the effective use of the space. It has, over a period of 20 years, become less and less capable of offering a programme of good-quality exhibitions.”

One by one, qualified employees have left and not been replaced, valuable items have been stolen and maintenance on the building has fallen behind. Many believe the museum is an embarrassment to the city.

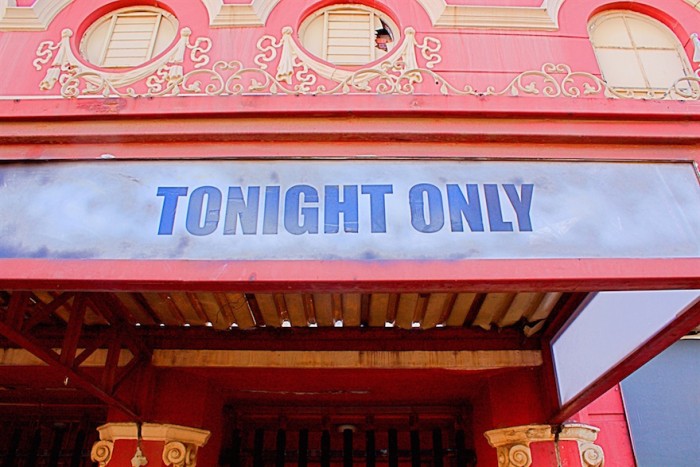

Head northeast to New Doornfontein, and the Alhambra Theatre is architecturally intact but in bad repair. It has been closed since 1994. Originally built as a cinema in the neorococo style in 1924, it retains an air of dilapidated grandeur.

Not far from here the 60s gem, modernist masterpiece Ster City, was once the jewel of the Ster-Kinekor crown. The once grand cinema complex is now boarded up, derelict and empty. It had three screens – one of them a 1 000-seater, but is now shut and so dark inside that only flash photography can reveal its tragic state.

“We are grateful that it’s inaccessible,” says Jude Bate, who has a computer business nearby. “Previously, it was a haven for thieves, who would hide inside. Now, at least crime has declined in the area.”

These are some of the more obvious stops through Jozi’s labyrinthine tour of vacancies, but the city is a veritable hall of smoke and mirrors. OR Tambo International Airport tells another tale. The inimitable mosaic walls, designed by Mozambique’s quirky and celebrated tropical modernist architect, Pancho Guedes, have been covered with prefab walling. The beautiful Italian terrazzo tiles have been hidden under cheap white Chinese ceramic ones, rendering one of many architectural gems generic and forgettable.

Jozi is not an easy place

Jozi is not an easy place in which to entertain visitors. The Gauteng Tourism Authority’s campaign is modest and quite telling. “Stay One More Day” it urges visitors, who generally arrive at OR Tambo and then depart immediately for their safari. Those who do brave another day might immerse themselves in apartheid history, but will experience little of the thing we all like most about Joburg – the people.

After all, this is essentially still a frontier town where anybody can strike gold and trampoline their way through hierarchies to success. But perhaps it is this very faculty for flux that has left us with such a fractured architectural narrative. On the upside, this same quality has provided the city with surprises. The wonderfully upbeat blooming of Maboneng, a new residential and retail district in what was a forlorn corner of the southeastern CBD, and the reinvention of Braamfontein as a vibey new social hub are both proof of Joburg’s capacity for renewal. So too, the myriad Pan-African communities that have sprung up in all parts of the city. And yet, on a continent obsessed with heritage, Johannesburg is a dangerous anomaly.

Last month, the Doll House, one of the city’s last roadhouses, in Highlands North, closed its doors. The building had no architectural significance. However, having been open since 1940, it was steeped in nostalgia for many of us who live here. It will be demolished and replaced by low cost housing. Its memory will haunt us. For such a dynamic metropolis to function so seamlessly as a ghost town should be of grave concern.

In her song, Big Yellow Taxi, Joni Mitchell wrote: “Don’t it always seem to go/ That you don’t know what you’ve got/ ‘Til its gone?/ They paved paradise/ And put up a parking lot”. One can only hope Joburg’s prime asset, its people, will remember our need for paradise before it’s gone.

Photos by Garreth-Leigh Lombard