Water is a source of life but when that source starts taking lives as a result of contamination, it puts the population at risk of serious growth and health challenges.

This is the case in Uganda where more than 10 million people lack access to clean, safe and drinkable water. Waterborne diseases, such as diarrhea have become the leading cause of death among toddlers and infants. A statistic that can have adverse effects on the country’s economy and population

Kathy Ku and John Kye, two Harvard graduates decided to address this problem after Ku spent time in Uganda as a teacher in 2010. Alarmed by the difficulty and high costs of obtaining safe drinking water, something she and millions of across the globe take for granted, Ku developed an alternative to current water filtration systems in the area.

After researching local raw materials and developing a sustainable business plan, Ku came up with the idea for Spout or “sustainable point of use treatment and storage”.

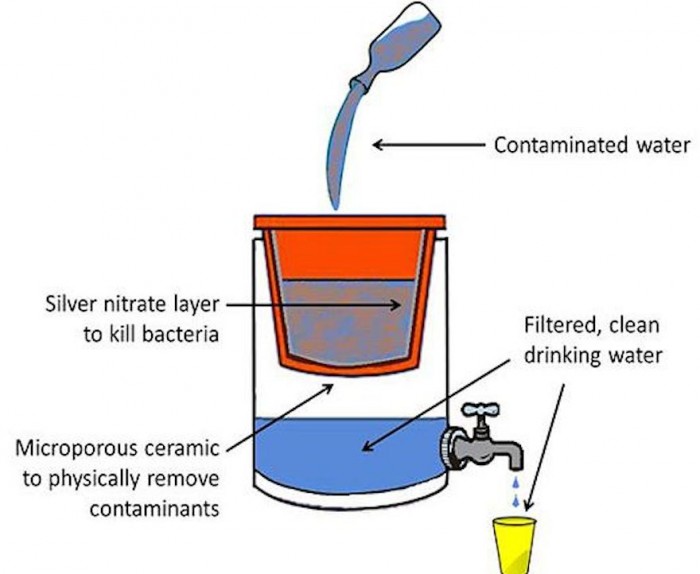

Clay and rice husks are shaped into buckets resembling terracotta flowerpots. They are then baked to harden. The rice husks combust during the firing process and leave minuscule holes that act as a mechanical filtration system. After the pots have cooled down, they are coated with silver nitrate, an inorganic biocide that kills 99.9 percent of microbiological contaminants.

Spout pots are safer, cheaper to produce, and easier to maintain than current filtration methods in the area. They provide better filtration and leave water with a purer taste than other methods such as chlorine tablets, bio-sand filters, ceramic filters, bottled water and even physically boiling water.

Ku and Kye have registered Spout as a non-profit organization and are driving all profits back into the factory. The profits are used to pay workers’ wages and educate local children on water safety. Ju says by selling the pots for around 69600 Ugandan shillings ($20) and not giving them away, they are breaking the cycle of aid and give people a sense of ownership, forcing users to look after their systems.