Every year in South Africa there is renewed shock and outrage at the country’s poor child literacy rates.

In 2017 the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study, which studied literacy levels between 2011 and 2016, ranked South Africa the lowest of 50 countries. It found that 78% of grade 4 learners were illiterate.

While there are a number factors to account for this result, the main one is the lack of a reading culture - not necessarily just in schools, but also at home and in the child’s immediate environment.

Multiple news publications shared the sentiment that the country was simply “not a reading nation.”

So what could possibly be done on a grassroots level to help fix this?

Frustrations with regard to this very issue is what inspired a movement on the other side of the Indian Ocean. Started by Nidhin Kundathil and Manoj Pandey, Sticklit is a collaboration between artists and writers which is aimed at making literature more accessible in India.

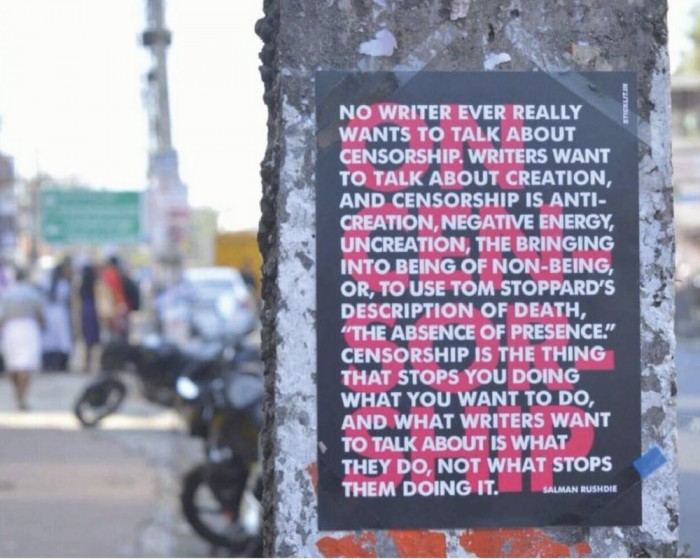

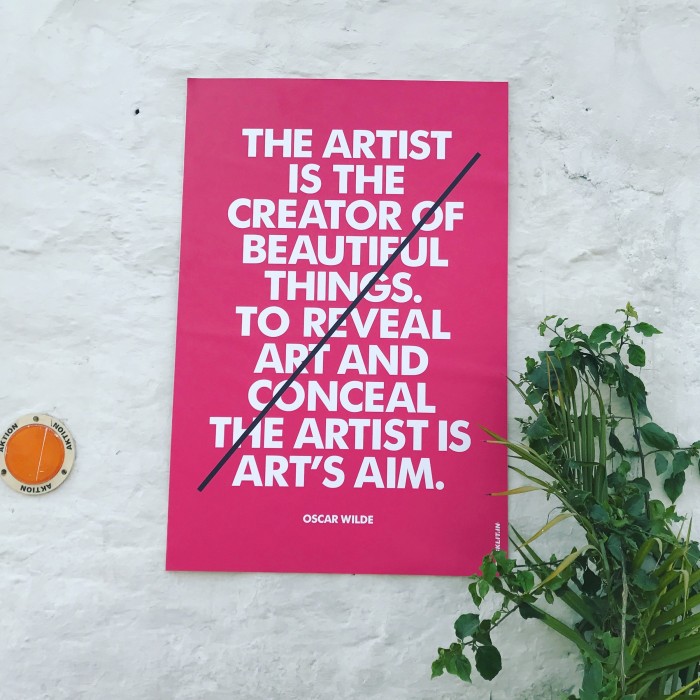

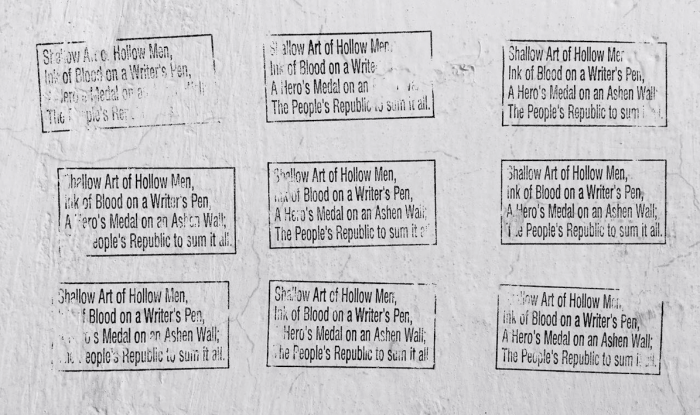

With the ambitious goal of creating the world’s biggest public library, specifically in public spaces, they’re taking iconic words and phrases to the streets using free-format stickers, posters and wall murals.

“In essence, we’re creating a free world for writers and readers. Just the way it should be,” reads their website.

Manoj explains that the selection process for these excerpts is pretty stringent, a far cry from frivolous inspirational sticker art. More than art, they see it as an intervention to democratise literature.

“We have a panel of experts who evaluate whether or not the contributors are serious about their pursuit. And whether or not they respect the process of craft,” he adds.

The panel of selectors includes college professors, authors and scriptwriters, while the artworks are created by Indian artists Malavika Sharma, Nikhil Manhaise, Ashish Pandey and Aadhya Baranwal.

Some of these have even moved beyond the streets and into gallery space, as Sticklit exhibited at India Art Fair in Motherland, Delhi in 2018.

Sticklit is also determined to extend their reach in rural areas, where they feel it holds a greater value - evidence of their commitment to the democratic literature project. But they can only move further into these spaces if public space is made available in order to support the cause.

“Given proper permission and opportunities, we can reach out to the more underprivileged members of society, who, when given the chance, might be even more receptive to good literature and art than first world elites,” Manoj says.

Just as in South Africa, India also has the added challenge of catering to a myriad of native tongues, in both urban centres and rural areas. As such, Sticklit incorporates Indian authors in their work too. “We have extensively given voice to Hindi, Kannadiga Nepali and other languages in India,” says Manoj.

Yet, the movement has gained traction beyond India’s borders, with iterations popping up in London, Amsterdam and colleges in North America. Furthering their democratic agenda, the artworks are freely available for download from their website with the goal of spreading the initiative globally.

“This is an open-source idea and we have no intentions of turning into another institution. For the idea is to democraticise the whole process and not to institutionalise it unnecessarily,” explains Manoj.

According to him, the project has opened up more conversation on the problem of basic education in India, a subject deserving of further discussion and intervention on a global scale.

This intervention is a very small step towards fixing the enourmous problem of poor child literacy rates, but it's a step towards encouraging a reading culture and a love of liteature in spaces where it is sorely lacking.

Read more:

A love letter to word with Naresh Ramchandani

Lauren Beukes on fiction as an incredible kind of telepathy

Egyptian comic book artists are writing their way out of censorship