From the Series

Designer Merel Witteman wants her work to disgust you. She knows that almost guarantees that you will look at it again. But she’s not doing it because she wants to demand your attention; she is raising awareness about the power of disgust, an emotion that has not been subjected to much critical analysis.

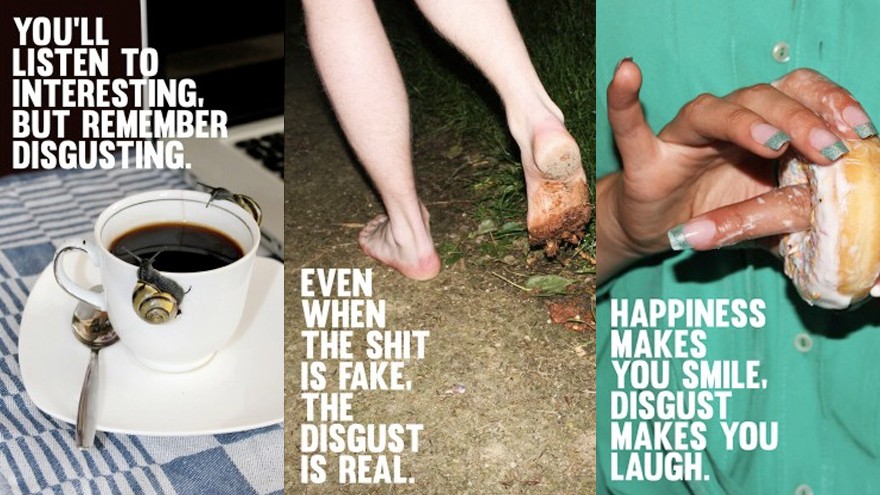

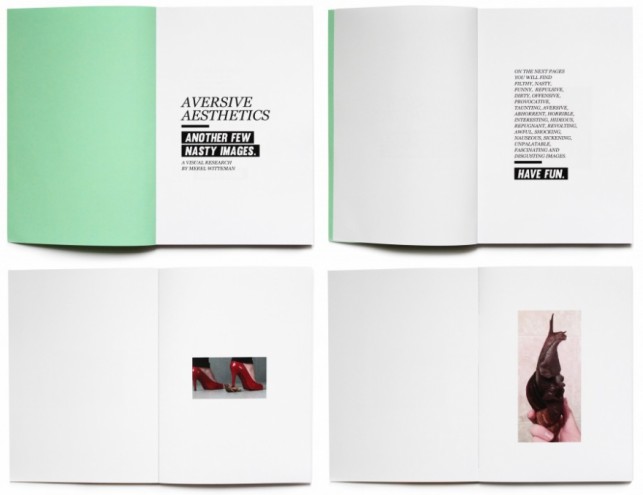

Witteman’s entertaining but toe-curling photo series from her 2014 Design Academy Eindhoven graduate project, Aversive Aesthetics, demonstrates her theory that disgust can play an extremely effective role in aesthetics.

Aversion has a paradoxical effect, says Witteman.

“As much as we want to run away from disgusting things, we feel attracted to them as well,” she says. “There is something so tantalising in the shock that we watch movies we don’t want to see, sniff at things we don’t want to smell, and listen to stories we don’t want to hear.”

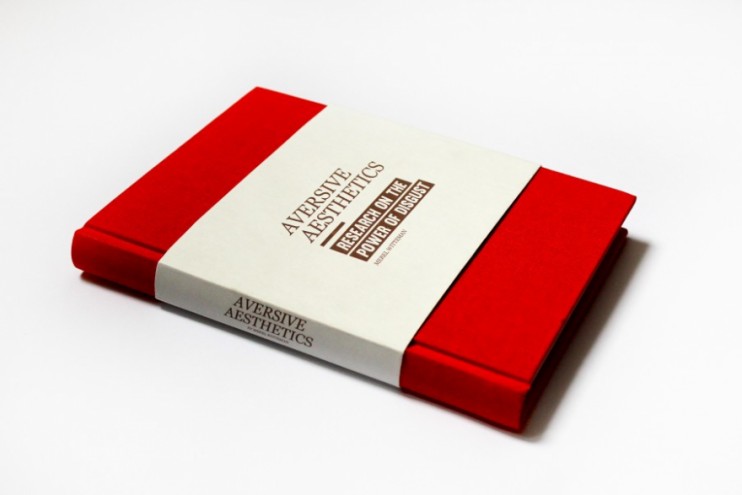

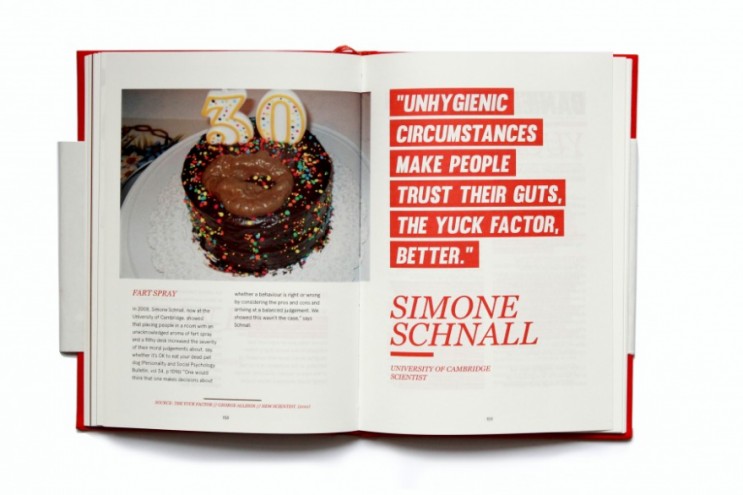

Aversive Aesthetics asks the question: is it possible to use disgust as an aesthetic value? Witteman conducted extensive research into the question, publishing her scientific and philosophical findings in a book.

Her visual study of the disgusting culminated in a campaign of photos that marry offensive images – impaled rodents, fake menstrual blood and donuts handled suggestively – with written statements that explain the dynamics of disgust. The funny thing is that while it’s clear all of the images are actually fake scenarios, our emotional response is the same.

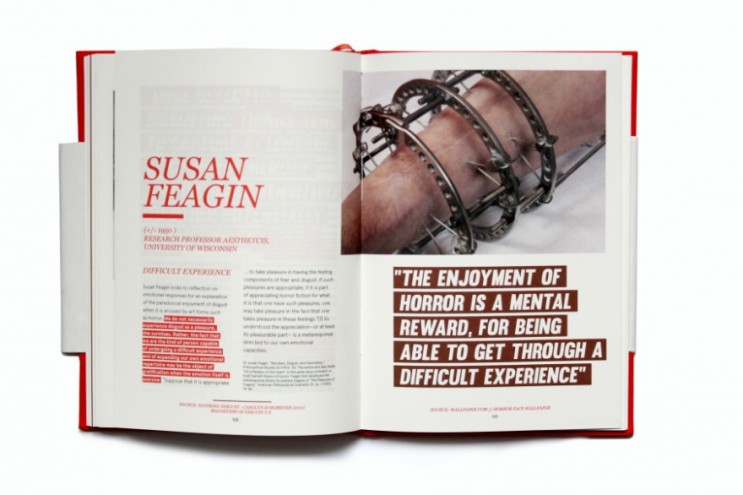

Witteman notes that aesthetic theories developed in the 18th century dictate that while disgust might be used to shock, it was not regarded as having any aesthetic value. As a designer, she was schooled in this line of thought and encouraged to make beautiful things.

But nowadays the role of the designer is changing, becoming more about telling stories, she says. She questions whether an emphasis on beauty is the most effective mode of storytelling.

I looked into the disgusting way of telling stories to see if you can enhance an experience when you trigger disgust in your audience, Witteman says.

Since the word “aesthetic” derives from the Greek for “I experience”, she determined that an effective aesthetic should trigger a deep emotional experience. Disgust fits this criterion, as it affects both the mind and body.

In short, we want to run away from disgusting things but at the same time we are made curious. This causes us to return to explore the disgusting. It’s an almost involuntary emotion. We’re sure to remember these things and we often want to tell others about it too.

“When the disgusting is disgusting enough to trigger disgust, but not too disgusting, it can enhance an experience,” Witteman says.

How do people respond to Aversive Aesthetics? “Overall, most people replied with a loud “ugh!”. A few seconds or minutes later they came back, checking the project for a second time.”

Since graduating, she’s started working as an art director at KesselsKramer, an Amsterdam-based communication and advertising agency. “If you can spread knowledge in a communicative way, you’re already bettering the world”, Witteman says. She continues to live by her design philosophy: “Don’t make crap”.