From the Series

An unprecedented 59.5 million people around the world have been forced to flee wars, poverty or persecution in their home countries. Refugees and stateless people escape across borders in search of safety and a place to start a new life. But inadequate shelter, a lack of financial support, stigma and discrimination, and unsanitary refugee camps are all challenges that continue to plague asylum seekers. Based in Amsterdam, the What Design Can Do (WDCD) 2016 conference has called on creatives across the globe to think up new ways to approach the crisis through its Refugee Challenge.

The challenge asks for solutions to five refugee problems: shelter and reception, personal development, the relationships between refugees and their host communities, the exchange of information, and ways to maximise their potential.

In part one of this story, we’ll take a look at a few of the designs that aim to offer refugees a sense of home by innovating the concept of emergency shelter. We’ll also look at the ways refugees could best maximise their personal development while waiting for asylum.

Shelter

The scores of refugee camps around the world serve as the legacy of the world’s conflicts. Sleeping in flimsy tents or in the open air, refugees have no option but to live in these inhumane conditions. To provide a safer more humane alternative, a group of Spanish designers from the University of Corunna created the DASY shelter. Its modular design is easily assembled and finished using a variety of materials. Made with comfort and security in mind, the shelter offers refugees as a dignified alternative to tents, helping them integrate into urban spaces.

According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), natural disasters forced 19.2 million people out of their homes in 2015. Emergency support is almost never readily available after the havoc of a natural disaster, leaving victims out on the streets until they can be rescued. With this problem in mind, Argentinian company Fundacionar created Cmax, an emergency shelter system that provides immediate housing for refugees. It was created to improve the quality of life of people made homeless by natural disasters, war and domestic violence.

The Cmax system provides living and sleeping quarters for a family of up to 10 and has sanitary units. While folded, these shelters are stackable, lightweight, and small and easy to store.

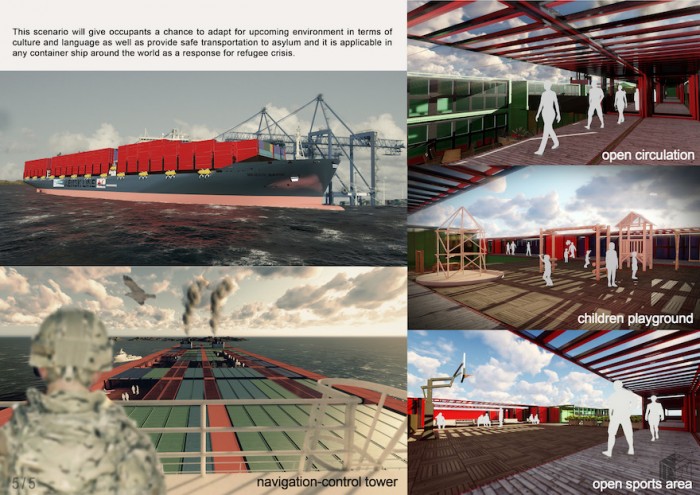

Safe transportation out of war-torn areas came to the fore in 2015 when a photograph emerged of a three-year-old Syrian boy lying lifeless on a Turkish beach. Like many others, he had drowned trying to escape Syria by boat. In 2016, as many as 2 500 refugees have drowned while fleeing to Europe. To provide security and safe passage, IBBM Design has proposed a Floating Disaster Relief Hub. Drawing on the well-known concept of using modified shipping containers to house refugees, the design team propose that the ships themselves be modified to house and transport refugees temporarily.

The already ambitious idea should also be self-sustaining, says the team. The camp’s specialised container modules are adapted for various functions like living quarters, police, fire department, health care, kindergarten, playgrounds, and other amenities. In order to provide refugees with the necessary amount of fresh greens during their travels, the team hope to introduce a Plant Factory module, which has a higher harvest rate than conventional greenhouses. Portable water is supplied at ports as well as through rainwater collection systems.

“This scenario will give occupants an opportunity to adapt to future environments during transportation in terms of culture/language as well as provide safe transportation to asylum,” writes the team. “It is applicable on any container-ship around the world as a response to the refugee crisis.”

Personal Development

After arrival at a refugee camp, all asylum seekers can do is wait. According to WDCD, this is time wasted. In camps all over the world, initiatives from outside and from within the camps have sought to rebuild the lives of refugees through educational programmes and artistic pursuits. A design team from Codomo and the SUTD-MIT International Design Centre have developed a similar approach in Togather.

Togather comes in three parts. The first is the designation of community squares. Here, the community can configure a public, educational space. The second phase introduces a Maker-Kit, a modular and reconfigurable furniture system that will allow refugees to create and develop their own unique and user-driven community spaces. The third step gives the refugee community autonomy to create their own programmes and uses for the space.

Building on the concept of community empowerment, Same Skies seeks to harness the skills already present in refugee camps. A number of asylum seekers are equipped with the skills to benefit their communities but are unable to work while in a transit camp. By harnessing their underutilised skills, Same Skies seeks to train and equip refugees to identify and mobilise their own resources and implement community solutions.

“We use innovative remote support strategies that other actors have so far only used as a last resort. Along with the social benefits, this enables us to be more cost-effective than common approaches,” writes Same Skies’ Julia Frei. “Furthermore, the involvement of refugees in all steps generates activities that are more culturally sensitive, context-specific and relevant.”

Around half the world’s refugees are children. The children are by far the most affected and most vulnerable in the refugee crisis. Refugee children are often unable to attend school and are vulnerable to exploitation, child labour, trafficking and more. To give these kids a fighting chance, Vanblend created the School Truck, a mobile education platform that enables teachers (refugees), children (refugees) and locals (students, volunteers and teachers) to come together.

Packed with books and educational games, the mobile school travels around transit centres with a number of volunteer refugee teachers. It facilitates interaction, provide information and teaches children about their host country in preparation for “real” school.

What Design Can Do (WDCD) has since 2011 called for design solutions to the societal issues of the time. The Refugee Challenge is a joint initiative of What Design Can Do, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and IKEA Foundation. The challenge sparked designers and innovators from over 69 countries to send in over 600 ideas. Submissions are now closed and designers are in the “improve” phase, which allows for community feedback and further development of their submissions.

The What Design Can Do 2016 conference in Amsterdam kicks off on the 30 June and 1 July, where the winning ideas will be announced.